In 1987, when James Baldwin visited Giovanni’s Room — Philadelphia’s gay and feminist bookstore that took its name from his seminal novel — it was a hasty affair. Baldwin was in town to see rehearsals of his play The Amen Corner at the Zellerbach Theater, and at the behest of his secretary, who over the years had received numerous invitations for Baldwin to visit the store, the author decided to pop in for a few minutes unannounced. He walked up to the second floor, greeted owner Ed Hermance, and offered to sign some books. He attempted to light a cigarette, to which Hermance said the building, unfortunately, was a nonsmoking one. And then he left. There was no time for fanfare, no time for celebration of the author who meant so much to so many.

In truth, James Baldwin, celebrated as he was, had nothing to do with Giovanni’s Room beyond the store’s name and his books stocked on its shelves. The people who had everything to do with the shop’s success over the last 50 years were, and still are, the LGBTQ community of Philadelphia. From the funds to secure the store’s home at 12th and Pine to the wood beams hammered in to hold the building upright, Giovanni’s Room was a labor of love by and for the community it was created to serve.

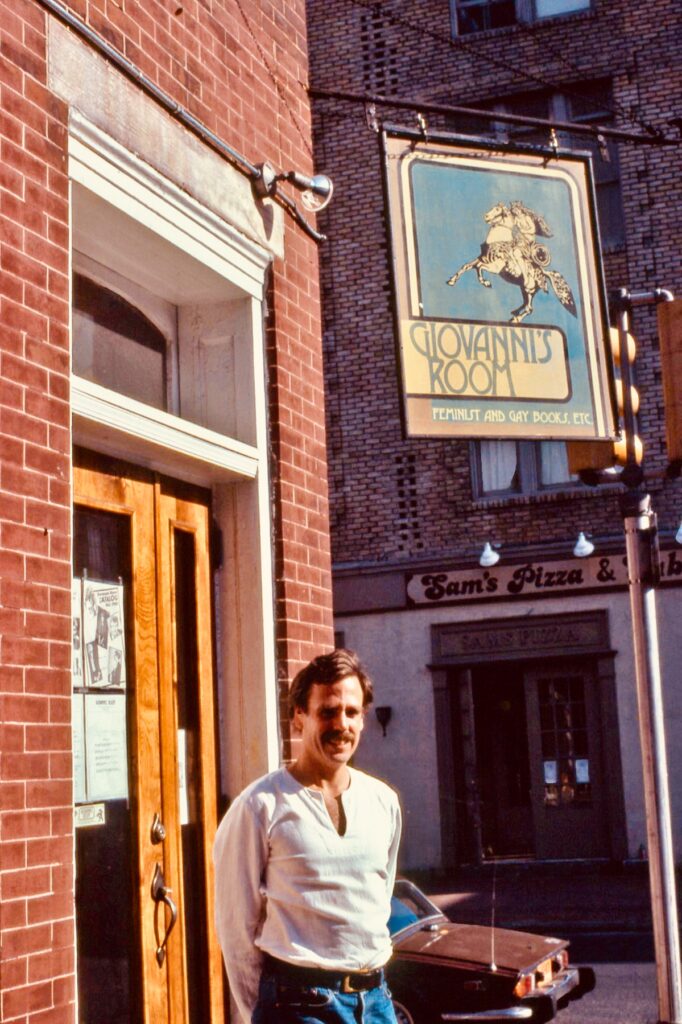

Opened by Bernie Boyle, Dan Scherbo, and Tom Wilson Weinberg in 1973, the shop started out in a one room storefront at 232 South Street. As was common for openly gay businesses at the time, the trio — who met each other through their involvement with Gay Activists Alliance — found it difficult to secure a location.

“For a while, we thought maybe we should just say we’re opening a bookstore,” Weinberg told PGN. “But then we thought that wasn’t a good idea, because a week after we’d move in, the landlord would know what we were doing and they’d be upset. So what we went through was rather humiliating, really. Some people thought it would be a porn store. They couldn’t imagine anything else out of a gay bookstore. But that’s not what we were doing.”

Eventually, the group found a friendly realtor who was able to secure them the space on South Street, and in August 1973, at $85 a month rent, the store opened with a large plate glass window, making visible everything that a heterocentric society had tried to mute.

Early on, the number of books geared towards the gay and lesbian community did not amount to much. The approximately 100 titles, which included works by Baldwin, Gertrude Stein, and Willa Cather were displayed cover to cover to help occupy more space on the shelves.

To help them figure out what books should be in the shop, the trio took advice from figures including Craig Rodwell, who had opened the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in New York City in 1967, and Barbara Gittings, who worked with the American Library Association to make books accessible.

“Craig had the books in mind that we could sell,” Weinberg said. “Barbara knew what people should read.”

The store was open six days a week, with each partner staffing it for two days each. But they enjoyed the store and its happenings so much that they’d often spend time at the shop apart from their shifts. Sometimes clientele — most of whom knew little of Philly’s LGBT world — would enter the shop and ask where the gay bars were; other times they’d ask more sensitive questions, to which they’d be referred to community resources such as the gay switchboard or the Eromin Center. Most times, Weinberg said, the feelings were good when people walked in.

It was fitting that the shop took its name from one of the most important works of gay literature of its time. When the three men were discussing what to name the shop, Weinberg, who had read “Giovanni’s Room” in the 1960s, suggested the title as they brainstormed ideas, which included The Bookstore That Dare Not Speak Its Name, after Oscar Wilde’s quote on gay love, and, jokingly, The Well of Loneliness, after the Radford Cliff novel.

““Giovanni’s Room” had meant so much to me,” Weinberg said. “And so we went along with that, but we called it Giovanni’s Room Gay and Feminist Bookstore. And then Pat Hill made it more feminist, which was great.”

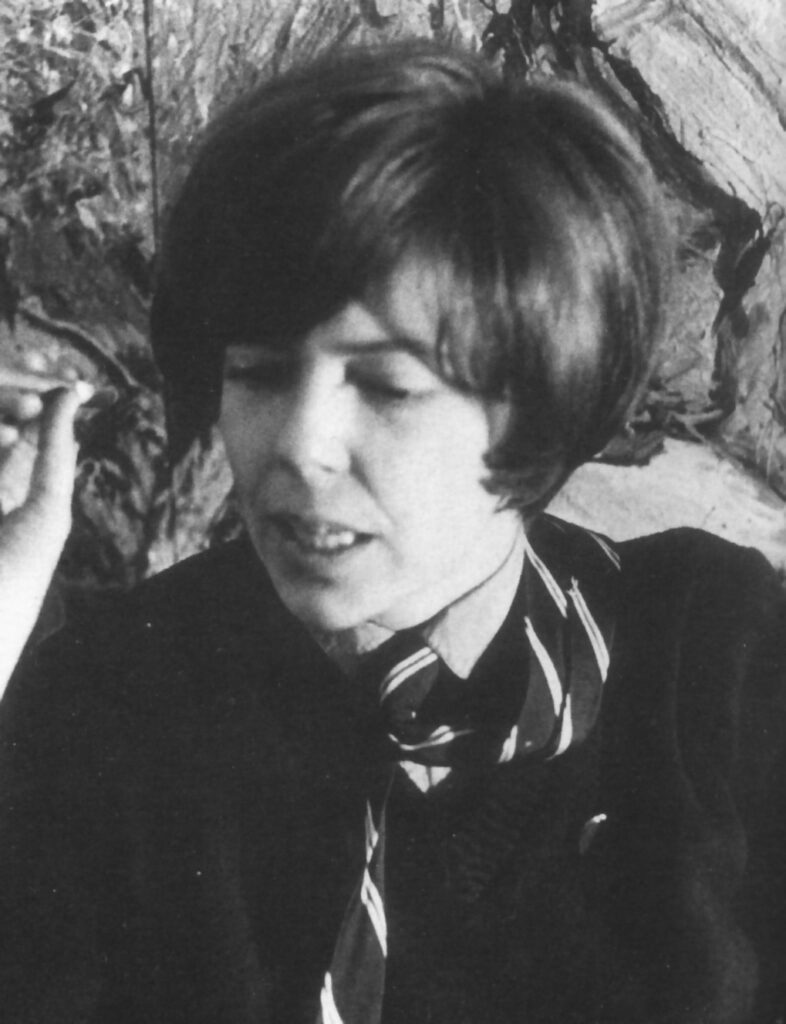

Hill, an artist who was working a civil service job for the Philadelphia Department of Parks and Recreation, purchased ownership of the shop from the three men in September 1975 for $500. She left behind a stable job for the far less stable prospect of gay and feminist bookselling.

“It was scary to give all that up,” Hill told PGN. “But it was so exciting and so necessary. How often do you get a chance to really make history a difference in history? I fell in love with it all. And a woman, to boot.”

The woman was author Dolores Klaich, who wrote 1974’s “Women Plus Women,” a social history of lesbians in America. Books like Klaich’s were among the new wave of titles housed at Giovanni’s Room that sought to inform and elucidate the LGBT community in ways that went beyond the often clinical depiction previously found in print.

During Hill’s time helming the shop, she expanded its lesbian and feminist offerings, taking book suggestions from customers and increasing the shop’s role as a place for community gatherings such as “Wine, Women, and Song,” which featured performers from the women’s music scene. Hill also created a lesbian publication called Wicce, where she wrote an article on the mistreatment of clientele at Rusty’s, a mafia-owned lesbian bar.

In the mid ‘70s, as the activist group Gay Raiders stormed broadcast news programs to increase national LGBT visibility, local visibility improved apace. Hill was asked to appear on a gay-themed episode of the Edie Huggins Show, a daytime show on WCAU, as well as speaking engagements at universities including Temple and Princeton. The gay, lesbian and feminist bookstore on South Street had reached ears far beyond the LGBT community.

More recognition, however, did not immediately equate to more sales. In 1976, a person could walk into Giovanni’s Room, be spotted by their employer through the plate glass window, and get fired the next day. Even if they mustered up the courage to browse, the number of true, must-have books that help keep bookstores in business, such as Rita Mae Brown’s “Rubyfruit Jungle,” were scant.

Any money made by the business was put right back into it by Hill. She applied for welfare and was first denied before pleading with the employee to reconsider, which he did.

“I always looked at that as a government subsidy of the gay movement,” Hill said. “But it was almost nothing. It would translate to more money today, but at the time it was $34 a week and food stamps.”

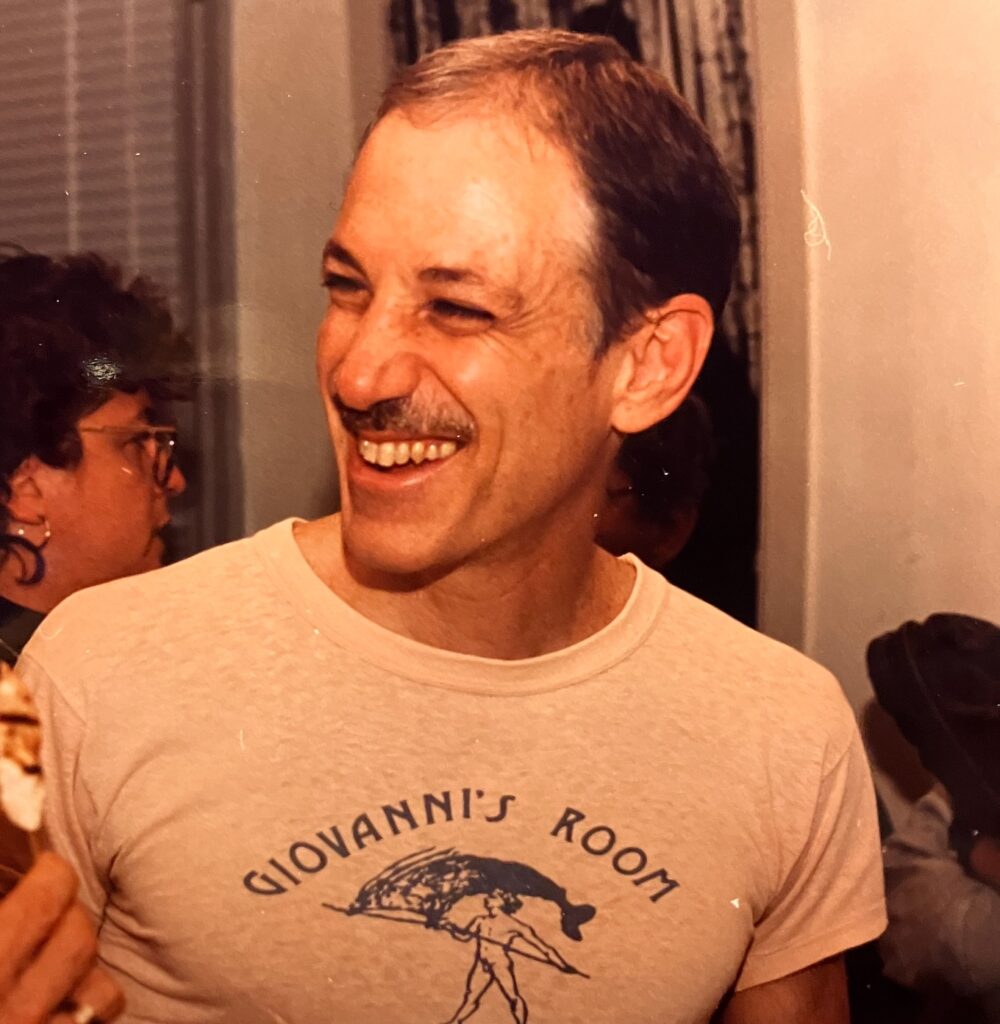

Hill celebrated her 40th birthday in the store, recalling a party that spilled out onto the street with champagne and a tuba player. Among those who attended the party was Arleen Olshan, who knew Hill from their days of community activism. When Hill decided to move on from Giovanni’s Room in 1976, she sold the business to Olshan and Ed Hermance, who led the store into a period that saw LGBT bookstores and the entire community grow rapidly.

Olshan and Hermance had met through their involvement with the gay community center at 326 Kater Street, where they served as co-coordinator and treasurer, respectively. The two liked the idea of a lesbian and gay co-owned community bookstore, so they bought Giovanni’s Room from Hill for $500 plus back taxes. At first, Hermance kept his job at the Penn Library while Olshan worked full time at the bookstore.

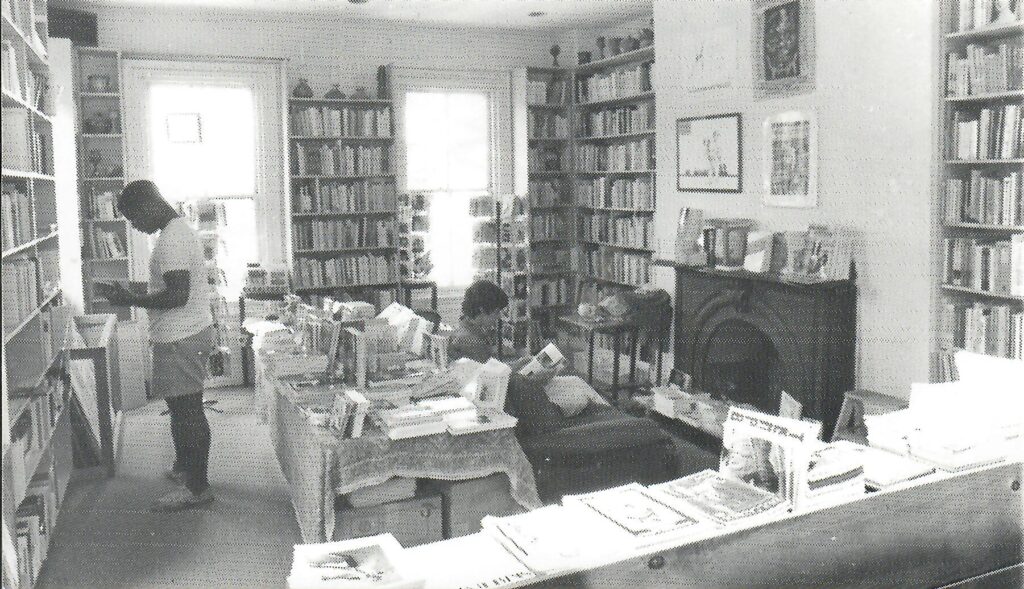

Almost immediately after purchasing the business, the new owners had to find a new location, since 232 South Street had recently been sold to a restaurant owner. Realtor Stanley Solo helped the duo find a reasonably priced space at 1426 Spruce Street, and the two began building the bookshelves, placing the turning rack, and outfitting the countertop. The publication New Gay Life, edited by Tommi Avicolli Mecca, for a short period kept its office in the back of the shop (which had previously been a doctor’s office).

“Basically, we were just open like all the time, from around 10 in the morning until midnight,” Olshan told PGN. “People would come in after work, they’d hang out. We had a lot of author parties there. We were open every New Year’s Day when the parade was on the street, and it was an open house and we’d serve food.”

Around the time Olshan and Hermance took over the store, openly gay editors like Michael Denneny began to push for more work by LGBT authors and for discontinued titles, such as those by Baldwin and Chrisopher Isherwood, to be reprinted. The energy to get more LGBT books into the hands of those who needed them was high.

Like Denneny, Oshan said she and Hermance would harass the publishing companies to bring older titles back into print, and when the pair attended events such as the American Book Association’s annual conference, they’d show publishers a list of books that needed to be brought back.

“Luckily, they listened to us,” Olshan said. “They heard that we were a population that was really underserved and that they could make money off of the gay and lesbian and feminist communities. And all of a sudden, the publishing industry boomed with our titles.”

What started with around 100 titles had grown into thousands of new and reprinted books as well as a growing base of LGBT publishers. Around nine months after they’d purchased the business, the business at Giovanni’s Room had grown large enough that it could support both partners.

“I think it was dumb luck that we started just at the moment when publishers were beginning to produce gay and lesbian books in sufficient quantity that it was possible to make a living from them,” Hermance wrote in a 2015 essay.

1976 had seen the release of Jonathan Ned Katz’s “Gay American History,” one of the first academic books of the post-Stonewall movement, as well as a scandalous title at the time, Fr. John J. McNeill’s “The Church and the Homo- sexual,” which challenged the Catholic Church’s antigay stance and argued that the Bible did not condemn homosexuality. Hermance recalled he and Olshan drove to the national convention of Dignity in Chicago — which had no gay bookstore at the time — to sell copies of McNeill’s book. Even The Vatican itself purchased a copy from Giovanni’s Room; Hermance recalled receiving an envelope with a check drawn from the Bank of the Holy Spirit.

“I wish I had taken a photo of that,” Hermance told PGN. “But I didn’t. I cashed it.”

As the number of openly LGBT people climbed alongside the interest in LGBT books, the store also began to host more and more well-known authors for events, including Allen Ginsberg, May Sarton, Audre Lorde, and Marge Piercey. But beyond the big events, the store became even more of a community hub for people to spend time in. The free flow and access to information, coupled with the ever-growing movement around LGBT equality, made Giovanni’s Room a natural destination for those looking to buy a book, get involved in LGBT issues, or both.

In 1979, three years after the business had moved to 1426 Spruce Street, the building was sold to a suburban family who did not want a gay, lesbian and feminist bookstore as their tenant. Hermance recalled them being so averse to LGBT issues and people that they refused to step foot in the store to tell them their lease would not be renewed.

“Nobody would rent to us on a tree street or a numbered street close to Center City,” Hermance said about the search for a new location. Among the spaces they were refused was Center City One, where the realtor said the shop would “attract too many homosexuals to our property.” While pondering what to do, Hermance had noticed a building for sale on the corner of 12th and Pine, though he figured purchasing it would require more money than they had on hand. But as the date grew closer, he and Olshan inquired about the purchase price and found out it was $50,000 with a $12,000 down payment. They received $3,000 from Hermance’s mother and nine $1,000 loans from members of the community, which were all paid back within five years. With the down payment secure, Giovanni’s Room relocated to 345 S. 12th Street.

The property required significant repair. Architect Steve Mirman volunteered to help redesign the space, and around 100 other volunteers tore down walls, built bookshelves and a skylight, installed lighting, put up drywall, spackled, painted, and moved and installed the iconic blue-green sign featuring an Amazon Queen on horseback and the title “Feminist and Gay Books, Etc.”

The hundred volunteers, along with the store’s first employee, Barbara Kerr, helped the store reopen at the new, two-story location on August 1, 1979.

As the world welcomed the 1980s, Giovanni’s Room welcomed its first sales to overseas bookstores, among them Gay’s The Word in London, Prinz Eisenherz in Berlin, and Les Mots a la Bouche in Paris. That arm of the business proved to be lucrative, since Europe saw far fewer LGBT titles released than America. To help save the overseas shops money, the store opened wholesale accounts with all major publishers. Staff of the European bookstores also visited Giovanni’s Room to take lessons from a well-run LGBT bookstore. Several recall the impact Hermance’s guidance had on them.

“A number of staff have made special visits to Giovanni’s Room over the years,” Gay’s the Word manager Jim Macsweeney said. While in town, Macsweeney also stayed with Hermance, who he said “not only knows an enormous amount about books, but is also a keen historian and brought me to visit Walt Whitman’s house in Camden New Jersey. It was a very special trip.”

The owners and staff at Giovanni’s Room, like those at Gay’s the Word, understood and appreciated the impact their businesses had on the local LGBT community. Giovanni’s Room cultivated an atmosphere of information sharing, curiosity, and above all else, acceptance. In the early ‘80s, such support was needed more than ever when the AIDS crisis stormed through the community.

The bookstore and its staff were, naturally, a clearinghouse of the latest information on AIDS. They published a bibliography of every known book on the illness, and they stocked pamphlets that city health workers would surreptitiously pass on to clients they thought needed them. But even more so than being an information hub, Giovanni’s Room was a place for people to deal with the personal realities of AIDS’ impact.

“People would get their positive diagnosis and would come from the doctor’s office to the store,” Hermance said. “And my sense is that they may have been interested in looking at the books, but I think they just wanted to find a safe space to think about this shock, about their relationships and their future, and wonder ‘what does this mean for me and everybody I know.’”

The store also saw the loss of several of its employees and volunteers to AIDS, including Black gay writer and activist Joe Beam, who had worked at Giovanni’s Room for six years before his death in 1988, and co-founder Bernie Boyle, who had been the one to first introduce Hermance to the store, in 1992.

Like many businesses owned by and serving the LGBT community, the store saw its share of discrimination. Staff and customers were verbally harassed outside. Bricks were thrown through the shop windows. Customs officials seized book shipments. Protests were staged around the contents on the shelves.

In 1986, Olshan left the business to pursue her art and other opportunities, leaving Hermance as the sole proprietor. That same year, Hermance’s mother — whom he credits with unintentionally instilling in him a spirit of activism and change — passed away, and he was able to use his inheritance to buy the adjoining building, 343 South 12th Street. With that purchase, the store had immediately doubled in size, and it was eight times larger than its beginnings on South Street.

The subsequent years saw the store’s sales reach their peak, with 1989 being the largest year at $788,327.46 from in-person store, wholesale, conference sales, and mail orders.

In the mid ‘90s, just before big chain bookstores stomped through town and online sellers decimated the local landscape, Giovanni’s Room had one of its largest selling titles in history: diver Greg Lougainis’ 1995 memoir “Breaking The Surface.” The lines for the book signing at the store extended two blocks, down Pine to 11th and over to Spruce. Men who were HIV-positive and found a role model in Louganis were joined by young divers and their parents who were inspired by Lougainis’ Olympic-winning performance. Random House, Lougainis’ publisher, had worried he might overextend himself by doing such a lengthy event, but the diver was firm in wanting to be there for people. In the end, it wound up being the store’s largest event ever.

Another of the store’s largest events, its 25th anniversary, drew guests including Chastity Bono, Andrew Tobias, Andrew Sullivan, Leslie Feinberg, Edmund White, Rita Mae Brown, Barbara Gittings, and Kay Lahousen. The silver anniversary celebration in 1998 featured a dozen readings and the largest slate of authors the store had ever seen.

From its peak, the declining sales at Giovanni’s Room — and all independent booksellers — began when large chains opened in Philadelphia and the surrounding region. Suddenly, fewer customers were passing through the doors and fewer authors held events there. Compared to the juggernauts of Barnes and Noble and Borders, smaller shops found it impossible to compete.

“As soon as [Borders] arrived in Philadelphia,” Hermance said, “I thought to myself, this is Big Capital. This store is not connected to Philadelphia, and when Capital has done its thing, they will simply move away and take their money elsewhere. And that’s exactly what happened.”

Hermance recalled authors including Lillian Faderman and Allison Bechdel doing events at other bookstores, despite the fact that those locations would only feature one or two copies of their book hidden among the stacks while Giovanni’s Room would be placing the books front and center in the shop for weeks.

“I said [to Bechdel] ‘this is a really big problem for us if you just go to Borders and not do an event with us.’”

Further cannibalizing the local book business was Amazon, whose practice of selling books below cost drew the ire of groups like the American Booksellers Association and led to an antitrust complaint to the U.S. Department of Justice.

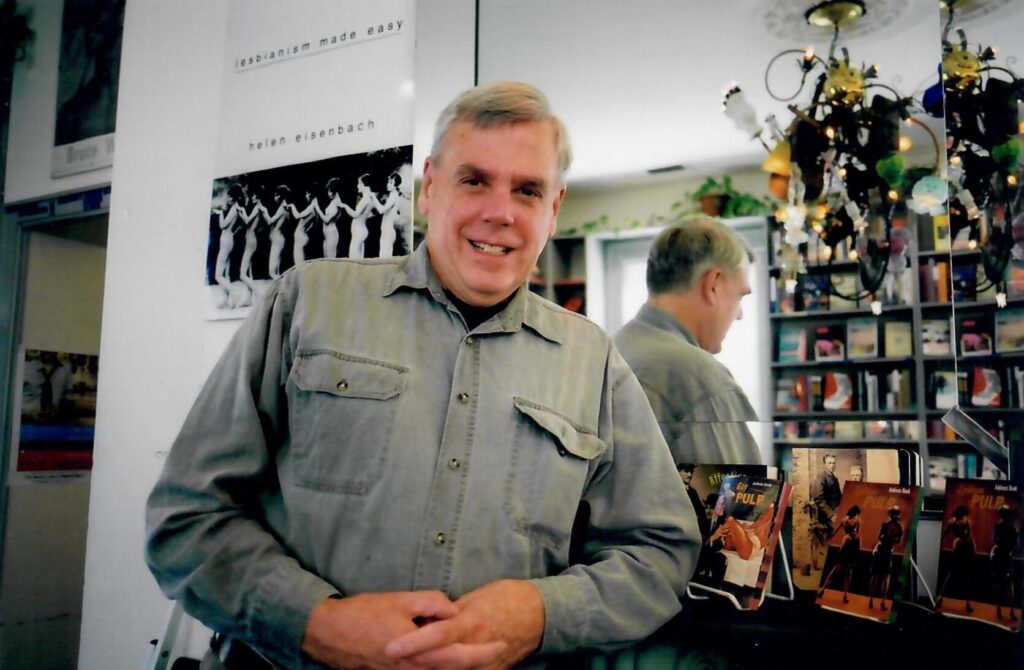

In 2013, after years of declining sales and a costly wall repair for the building, Hermance, who had led the store for almost four decades, announced his plans to retire. The store closed in May 2014, but found new life when the nonprofit Philly AIDS Thrift signed a two-year lease to rent the building and opened in October 2014 as PAT @ Giovanni’s Room.

“We’re in the business of preserving precious things and what can be more precious than Giovanni’s Room?” PAT co-founder Christina Kallas-Saritsoglou said when the deal was completed.

That iteration of the shop, which has continued ever since, functions as a hybrid thrift store and bookstore, featuring donated books, movies and clothing, as well as new books. But despite the ephemera lining some shelves and cabinets, the main focus of the store remains books, which are sold in-store and online at queerbooks.com/.

“We have customers who have been coming here since the 70s and 80s, and that’s something genuinely special and genuinely wonderful,” said Katherine Milon, who co-manages the store with Christopher Cirillo. “And I want to keep those people feeling like they have a place in the store and the store’s history and culture. But I’m also getting really excited about the idea of making the store a little more well known in other age groups and other demographics.”

Milon touted the store’s book club, which launched last year and has seen upwards of 30 people attend in-person discussions of titles such as “All This Could Be Different” by Sarah Thankam Mathews, as well as the renewed interest in classics like Leslie Feinberg’s “Stone Butch Blues” and bell hooks’ “all about love.”

In celebration of the store’s 50th anniversary, PAT is hosting a June 10 block party in front of the store called QUEERAPALOOZA, featuring a DJ, performances, local queer vendors, and food and drink. There is also discussion of an event in the fall honoring the store’s previous owners dating back to its 1973 beginnings.

“When I was younger, I went to every shop I could to find the literature that I wanted,” Olshan said. A lesbian, gay and feminist bookstore that carried everything in one space was something she’d wanted to see happen. Giovanni’s Room served that need, not just for herself, but for all LGBTQ people who were trying to find their way.

“It was a very exciting period of time, both politically and emotionally. Very satisfying from a sense of community building community.”

That idea of community building, of the store serving as not just an informational hub, but a social, cultural and political touchstone for LGBTQ people, is something that was built over decades through the work of its staff and volunteers. In 2011, the store was recognized with a state historical marker that reads: “Founded in 1973 and named after James Baldwin’s second novel, Giovanni’s Room served as bookstore, clearinghouse and meeting place at the onset of the lesbian and gay civil-rights movement, a time when one could be ostracized, arrested or fired for loving someone of the same gender.”

The times may have changed over the last half century — from the shifting publishing world to the HIV/AIDS crisis to the anti-LGBTQ book bans sweeping the country today — but Giovanni’s Room has remained steadfast in its role of bringing people books and helping to build a community.

“It occurred to me that if you stay in one place long enough, things really kind of come together,” Hermance said. “All of these ties get knotted.”