When bell hooks died on December 15, 2021, it was a gut-punch. There was no time when bell hooks’ extraordinary writing and feminist and lesbian theorizing was not part of the queer community. There was no time when the community imagined that hooks’ voice would not always be in the forefront of our collective consciousness on intersectionality and queer theory and praxis.

Intersectionality has become a political and cultural buzzword recently, yet few have read the intersectional essays of hooks or Kimberlé Crenshaw, who invented that concept and wrote (and continues to write, in the case of Dr. Crenshaw) about it exhaustively and, as Audre Lorde would say, deliberately. Intersectionality describes and explores how race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and class might intersect with one another and overlap.

The extraordinary breadth of hooks’ writing and the thematic structures of her books, essays, and poetry all build on each other. She writes so much of love, so compellingly of emotional and romantic commitment and what it means, that it was stunning when hooks revealed she spent the last two decades of her life unpartnered and celibate.

In an interview for Shondaland in 2017, hooks told Abigail Bereola, “I don’t have a partner. I’ve been celibate for 17 years. I would love to have a partner, but I don’t think my life is less meaningful. I always tell people my life is a pie and there’s a slice of the pie that’s missing, but there’s so much pie left over — do I really want to spend my time looking at that empty piece and judging myself by that?”

In that same interview, hooks delves deeply into one of her pivotal topics: self love and what it means for women to love themselves and recognize that they are worthy of commitment and that they do not deserve violence or other oppressive acts in a relationship.

As hooks told ESSENCE magazine in another interview, “I think the revolution needs to be one of self-esteem because I feel we are all assaulted on all sides… I think Black people need to take self-esteem seriously.”

In the era of white MAGA GOP grievance, the fear of losing the prioritization of whiteness and cis-het maleness has subsumed much of our political discourse, which makes hooks’ work more crucial than ever and her recent death all the more painful a loss.

Born Gloria Jean Watkins on September 25, 1952, hooks began using her maternal great-grandmother’s name as her pen name in 1976. She lowercased her name to signify that she wanted people to focus on her books, not “who I am,” as she explained in a talk at Rollins College in 2013.

Over the four decades of her writing, hooks wrote continually about Black women, about feminism, about the oppressive nature of patriarchy, and about how Black men had embraced that even as they decried white imperialism. In her 1981 feminist classic, “Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism,” hooks deconstructed a panoply of issues from slavery to the devaluation of Black women and Black womanhood.

She wrote declaratively that “No other group in America has so had their identity socialized out of existence as have Black women… When Black people are talked about the focus tends to be on Black men; and when women are talked about the focus tends to be on white women.”

She wrote, “A devaluation of Black womanhood occurred as a result of the sexual exploitation of Black women during slavery that has not altered in the course of hundreds of years.”

Later, in “Remembered Rapture: The Writer At Work,” hooks expanded that discourse, noting, “No Black woman writer in this culture can write ‘too much’. Indeed, no woman writer can write ‘too much’ … No woman has ever written enough.”

True to her advice, hooks was always writing more and building on her previous ideas and theories. There is no disengaging of historical and cultural events in hooks’ work. She sees everything through a prism of contexts that each impact each other — hence the violence of nationalism cannot be divorced from domestic violence. She could see these links so clearly and write about them with such clarity, precision, and accessibility, that the reader was left convinced and educated.

In a 1995 conversation with digital activist and lyricist John Perry Barlow, hooks said, “I have been thinking about the notion of perfect love as being without fear, and what that means for us in a world that’s becoming increasingly xenophobic, tortured by fundamentalism and nationalism.”

We are in that time now, where the MAGA GOP has combined fundamentalism and nationalism and added a soupcon of xenophobia. The prescience of hooks’ readings of the Zeitgeist and the moment was a critical aspect of her oeuvre as a writer and theorist.

This was true even of her own identity. Though many people referred to hooks as a lesbian or gay, she preferred queer. Describing herself as “queer-pas-gay,” hooks inserted the French word for not — “pas” — and said that she chose that term because being queer is “not who you’re having sex with, but about being at odds with everything around it.”

In an event at The New School on May 6, 2014 titled, “a conversation with bell hooks,” the then-scholar-in-residence at Eugene Lang College at The New School for Liberal Arts spoke at length about this issue.

She said, “As the essence of queer, I think of Tim Dean’s work [the British queer theorist] on being queer and queer not as being about who you’re having sex with — that can be a dimension of it — but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it, and it has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

The details of hooks’ life helped build her perspective and her feminist and queer theory. She was born and died in Kentucky and often wrote about living in Appalachia (a region which is often associated with whiteness), but she lived most of her adult life elsewhere. She had several degrees: a BA from Stanford University, an MA from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and a PhD from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She also worked across the country as a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, San Francisco State University, Yale, Oberlin College and City College of New York.

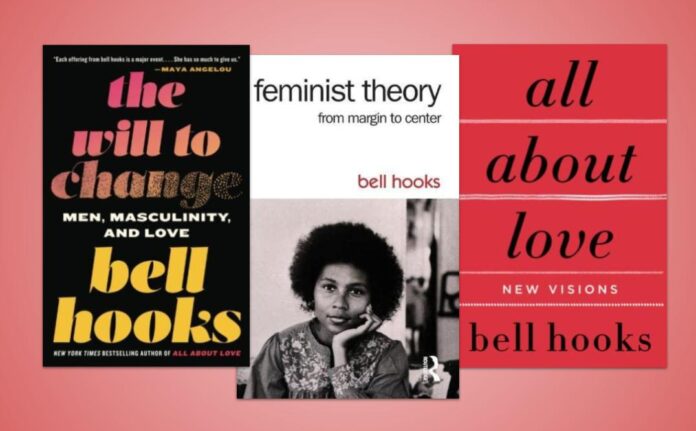

True to another of her sayings, “I will not have my life narrowed down. I will not bow down to somebody else’s whim or to someone else’s ignorance,” hooks published prolifically, with over 30 books and dozens of chapters and essays in the books of others. Her publications included the iconic “Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center” (1984), “All About Love: New Visions” (2000), “Feminism is for everybody: passionate politics” (2000), “We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity” (2004), “Soul Sister: Women, Friendship, and Fulfillment” (2005) and “Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice” (2013). She also wrote several children’s books, including “Homemade Love” (2002).

Among the issues hooks wrote about in her books was the confluence of health, mental well-being and racism. In the last decade of her life, struggling with the renal disease that ultimately killed her, she moved back to Kentucky. On her return to her birthplace, hooks compared her journey to that of author Wendell Berry. “Our trajectories are very similar,” hooks told PBS, “because he went out to California, New York, the places that I too went, and then felt that urge, that call to home, that it’s time to come back.”

There are so many things to be said about hooks’ life and work, so many visionary concepts she developed and nurtured and expanded upon. But at her core, hooks was always writing a paean to love. She wanted love to equilibrate the world, to mitigate violence, to assuage the pain of racism, misogyny, homophobia, classism.

In “Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations,” hooks wrote, “The moment we choose to love we begin to move against domination, against oppression. The moment we choose to love we begin to move towards freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others.”