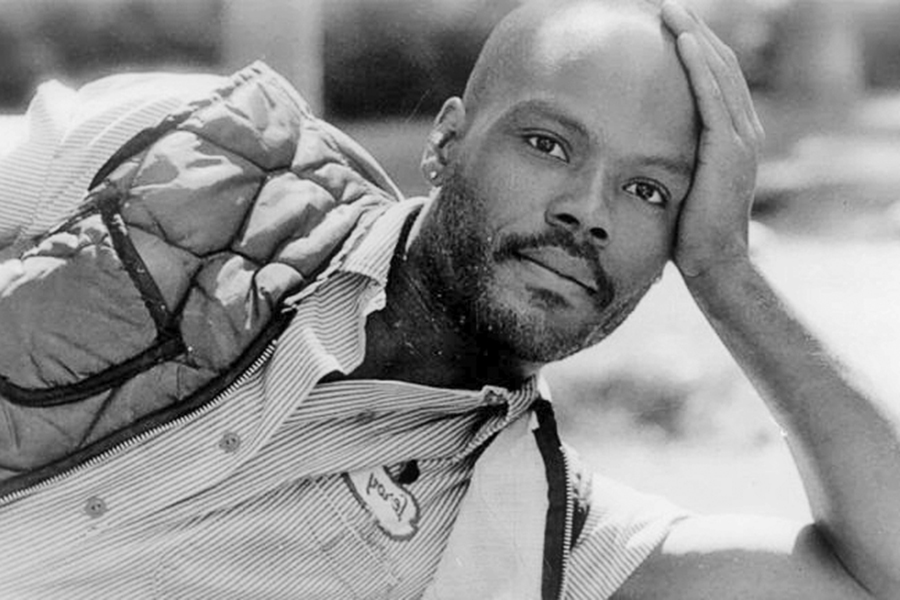

Joseph “Joe” Beam was the editor of the 1986 collection “In the Life: a Black Gay Anthology” — the first compendia of black gay writing. Beam was a board member of the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays and a founding editor of Black/Out magazine. His work appeared in numerous local and national publications, including PGN, The Advocate, Au Courant and Windy City Times. Beam served on the Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Friends Service Committee.

In 1984, the National Lesbian and Gay Press Association honored him with an award for outstanding achievement by a minority journalist. Beam also maintained ongoing correspondence with prisoners, which he later attributed to a “deep sense of my own imprisonment as a closeted Gay man and an oppressed Black man.”

Prior to his death, Beam had been working on the book “Brother to Brother,” a sequel to “In the Life.” While he was unable to finish it, Philadelphia poet Essex Hemphill and Beam’s mother, Dorothy, completed the collection. Dorothy Beam died in December 2018 at the age of 94 — a driving force in her life was keeping her son’s legacy alive.

Dorothy Beam invited Hemphill to move into her home in Overbrook so they could finish her son’s book together. Hemphill handled the editing and Dorothy worked as a project coordinator. The result, “Brother to Brother: New Writings by Black Gay Men,” was published in 1991.

“My reason for finishing the book is that my son worked hard to finish it,” she told the Inquirer in 1992. “If there is a heaven, he’s there and he’s smiling.”

For a long while, the life of Beam, a Philadelphia poet, essayist, editor, feminist ally, black and AIDS activist was overshadowed by his death. One of the shining lights of Philadelphia’s Black LGBTQ literary community, Beam was found dead by friends on the floor of his Center City apartment on Christmas Eve 1988. He had been dead for days.

In those years, AIDS claimed many lives, but Joe Beam’s death shocked the community. It spoke directly to how the LGBTQ community fell short in looking after each other — something Beam had written about time and again. It was, in many respects, his life’s work: highlighting the voices that were suppressed and silenced, the lives that had been hidden from history, the work that had not been published because its authors were marginalized by straight, white, cis male society.

Joe Beam, for all his many literary accomplishments and activist credentials, was known for his charming, charismatic and caring persona. Beam made others feel heard. When he spoke, he connected, whether with an individual or an entire room.

In the ’80s, during our interview, Beam said, “We must begin to speak of our love and concern for each other as vigorously as we argue party politics.” This was a mantra of his. The love and concern he evinced for so many in his community made the circumstances of his death that much more painful — all who knew him would have wanted to be with him.

Joe Beam was a week shy of his 34th birthday at his death. At this year’s Stonewall 50, he would be 65. Three decades of his incendiary work are missing from the LGBTQ lexicon and canon. That was the toll AIDS took on the LGBTQ community. Beam’s voice was and is critical, crucial and revolutionary.

As Yolo Akili Robinson wrote about founding the Black Emotional and Mental Health Collective (BEAM), “I want to help create a world where what happened to Joseph [Beam] could never happen to anyone else. “

Beam’s close friend, poet and journalist Tommi Avicolli Mecca wrote a poem, “For Joe Beam,” which begins, “They found you dead on the floor of your bathroom / three days dead / found you alone / xmas eve dead.”

Beam’s death propelled many in the Philadelphia LGBTQ literary community to ensure that Beam’s work be preserved and promoted. Robinson wrote of what Beam meant to black gay men.

“His writings were the first time I had ever heard Black men speak about their feelings, their fears and struggles in such a vulnerable manner,” Robinson said. “His commitment to Black feminism, and challenging male privilege in both gay and heterosexual communities, became a central organizing force behind my own beliefs. The struggles he captured made it clear to me that mental and emotional wellness, were of an immediate need for our communities to be able to thrive.”

Beam wanted his community of poets, of black gay men and black lesbians, of AIDS activists, to thrive and dedicated himself to that work as a writer, editor and activist. He felt nurtured by the work of other activists and writers and said that among the work of which he was most proud was amplifying those voices. He interviewed Audre Lorde and Samuel Delaney — two black gay literary heavyweights — for Black/Out. He culled the work of so many disparate black voices for both of the books he published. Working at Giovanni’s Room bookstore, he promoted books by black writers and ensured that the inventory included black voices.

Beam wrote, “By mid-1983, I had grown weary of reading literature by white Gay men. More and more each day, as I looked around the well-stocked shelves of Giovanni’s Room … I wondered where was the work of Black Gay men.”

Thus began “In the Life.” He said his book spoke for “the brothers whose silence has cost them their sanity,” as well as the “2,500 brothers who have died of AIDS.”

In “Making Ourselves From Scratch,” one of Beam’s essays in “Brother to Brother,” he wrote, “My desk and typing table anchor the northeast corner of my one-room apartment…. On the walls surrounding me are pictures of powerful people, mentors if you will. Among them are Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, John Edgar Wideman, Essex Hemphill, Lamont Steptoe, Judy Grahn, Tommi Avicolli….”

In his editor’s note in the second issue of Black/Out, Fall 1986, Beam wrote about “Black pride and solidarity.” He said the journal was “part of a worldwide movement that will enliven and reshape the discussions of race, sex, gender and class oppression. Our movement is one of liberation; our vision is one that is dignified and inclusive….The progressive movement of Black Gays and Lesbians is one into which we have been born; ours is a birthright to struggle. Our sole decision is what part each of us will play within this new movement.”

Beam did recognize that for black lesbians and gay men even more than their white counterparts, being out was not an easy path, writing “Understandably, all of us cannot or will not carry placards proclaiming our sexuality in the workplace, at home or in the streets. But there are other tasks to be done; indeed, many ways to be an activist.”

But Beam was out, and he was in the streets, and he was also inclusive. Philadelphia writer and trans activist Cei Bell wrote about Beam and LGBTQ racism for the 30th anniversary of “In the Life” in an essay for WHYY NewsWorks.

Beam had published her groundbreaking work in Black/Out. She said, “Joe edited an article I wrote about the murders of transgender black women for Black/Out magazine. He wanted me to submit an essay for “In The Life,” but I thought it was inappropriate, as a transsexual woman, to write for a gay men’s anthology. I supported Joe by helping him proof the galleys. This is why I appear in the book’s acknowledgments.”

Racism was a persistent and essential theme in Beam’s work, and he spoke often of the micro- and macro-aggressions of being a black gay man in white America. In her essay, Bell recounted several of Beam’s experiences with racism that he had shared with her, among them being ignored by white coworkers when on the streets of Philadelphia or in the bars.

“When I wrote about racism in Philadelphia restaurants in the ’80s,” Bell said, “Joe told me about his difficulty finding work as a waiter. It was easy for white college graduates in the arts to wait tables, but not for black college graduates in the arts.”

From the pages of Black/Out, Beam called for his community to, “collect books for our sisters and brothers who are incarcerated,” to work to end homelessness and illiteracy among black lesbian and gay people.

Charles Stephens and Steven G. Fullwood co-edited the 2014 anthology, “Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call.” In a conversation with Lambda Literary, Stephens said, “I lacked the language to describe what I was longing for, and perhaps in a sense Beam, and his stunning vision of community, provided that language for me. I absorbed his words, and found a home in them. “In the Life” became a compass for me, to first locate myself, and then others that shared my commitments.”

The Schomburg Center’s Fullwood talked about being a “teenager in Toledo in the 80s” and how a woman friend found “In the Life” at the library and Xeroxed pieces from the book for him.

“My heart raced,” Fullwood said, “Writings by several self-identified black gay men. I read those pages with nuclear bombs going off in my head. Coming out stories. Sexual encounters. Homophobia. HIV/AIDS. Romance. Political activism. I couldn’t believe my good fortune. Something in me took root and wanted to flourish.”

Beam was only 15 when Stonewall happened, but the work he did was of a similarly revolutionary character. Beam opened the door for black gay men to speak their truth, to reveal their feelings, to be their authentic selves without fear.

He said, “I dare us to dream that we are worth wanting each other. Black men loving Black men is the revolutionary act of the eighties.”

Joe Beam moved the LGBTQ community forward, made people acknowledge racism, black excellence and black gay love.

He wrote, “Living a lie is one thing, but it is quite another to die within its confines.” Joe Beam lived as authentic a life as one could imagine. That authenticity, that truth, is his legacy.