Betty Friedan co-founded Radicalesbians in 1970. It wasn’t the intent of the straight and openly homophobic co-founder and first president of NOW, the National Organization for Women, but it was the result of her purge of lesbians from the fledgling organization. Friedan had called lesbians the “lavender menace” in a 1970 New York Times interview. She and other well-known straight feminists thought lesbians threatened the organization by giving the appearance that NOW was filled with “man-haters.” Friedan and other straight feminists were concerned that the presence of “mannish” or “man-hating” butch lesbians would hinder the cause. Among those Friedan fired was writer Rita Mae Brown, who was editor of the NOW newsletter.

Brown would go on to co-found Radicalesbians a few months later, after declaring that “lesbianism is the one word which gives the New York NOW Executive Committee a collective heart attack.”

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was also an inadvertent co-founder of Radicalesbians. While some men involved in GLF were attuned to sexism within the nascent movement, others were not. And many lesbian activists felt as separate from the gay men of GLF as they did from straight women of NOW.

After Friedan’s actions at NOW, a group of GLF women — including Brown and author and academic Karla Jay — organized a protest to disrupt the Second Congress to Unite Women in May 1970. The NOW-sponsored Second Congress to Unite Women had blatantly ignored lesbianism in its planning: “not a single speaker, workshop, or plenary involved an open lesbian.”

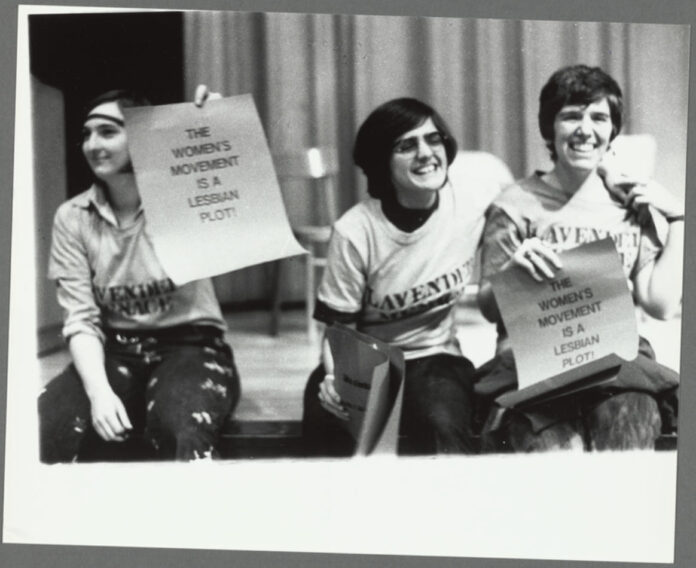

The lesbian activists wore T-shirts that read “LAVENDER MENACE,” which had been dyed lavender in one woman’s bathtub and hand-stenciled. One of the shirts is now displayed at the Lesbian Herstory Archives. The women passed out copies of their manifesto, “The Woman Identified Woman,” which would become a defining treatise for lesbian feminism and the founding document for Radicalesbians. The Lavender Menaces of that first action would re-form and re-name themselves Radicalesbians.

And so on May 1, 1970, about 20 of these lesbian activists infiltrated the Second Congress to Unite Women. At the beginning of a panel discussion that had drawn about 400 women to the auditorium, the group turned the lights off. When the lights came back on, women wearing Lavender Menace t-shirts had taken over the stage and posters reading TAKE A LESBIAN TO LUNCH, SUPERDYKE LOVES YOU, and THE WOMEN’S MOVEMENT IS A LESBIAN PLOT had been hung on the walls throughout the auditorium.

One activist explained to the audience: “We have come to tell you that we lesbians are being oppressed outside the movement and inside the movement by a sexist attitude. We want to discuss the lesbian issue with you.” While some women left, nearly all stayed as the lesbian activists explained their mission.

“The Woman Identified Woman,” situated lesbianism at the center of feminist politics, defining lesbianism as a political, cultural and sexual resistance to patriarchy. As members of the group would later assert, “Feminism was never the same again.”

This action — and the manifesto, itself — formed a template for lesbian activism. Over time, other feminists who did not define themselves erotically as lesbians declared themselves “political lesbians” as an action of solidarity with lesbians and to their commitment to other women and to feminism. That term is still maintained by women who define themselves as “radical feminists.”

In the early days post-Stonewall, lesbian activists continued to work with their gay male peers. But as feminist consciousness pervaded the lesbian activist community, many women chose to do that activist work exclusively with lesbians and to create woman-only spaces. These new spaces provided the ground for the cultural and political work of lesbian feminism.

Ellen Shumsky, a member of GLF and Radicalesbians, wrote and spoke about conflicts between men and women in GLF. Shumsky said tensions between men and women in GLF blew up in early 1970, concomitant with the NOW purge. GLF women proposed hosting their own dances. GLF dances provided an alternative to the Mafia-controlled bars. But as Shumsky explained, these dances were “overwhelmingly attended by males,” and women had grown weary of “the ‘pack-’em-in’ attitude” of the dance organizers. GLF women, Shumsky among them, wanted a different, more inclusive, less daunting and more female-identified space for women to dance and get together.

There was anger among the GLF men that women wanted separate spaces that barred men — and a lack of understanding that men, even gay men, were still the oppressors of women. GLF men objected to the use of GLF funds to provide space for women-only events.

All these things simmered together — the exclusion of lesbians from the women’s movement and the feeling lesbians had about being excluded from their rightful and equal place in the gay liberation movement.

So in 1970, a group of GLF women and those purged from NOW coalesced to form the lesbian activist group Radicalesbians. The group was the first post-Stonewall activist group solely for women. Prior to that, only Daughters of Bilitis had focused on lesbians only.

Radicalesbians was created to provide a supportive community that gave lesbians a voice in the gay and women’s liberation movements, and to take action against their oppression. They picketed lesbian bars in an effort to reach out to less political women, contributed to feminist publications like Rat, spoke about lesbianism at colleges and on radio shows, and participated in activities like self-defense classes at an All Women’s Night at Alternate U in New York City.

Shumsky detailed the rise and fall of Radicalesbians in a long read for the Gay & Lesbian Review in 2009. Shumsky had previously written about the formation of Radicalesbians for the December-January 1970 issue of “ComeOut!” which likely had a very different tone to her piece 39 years later, which is regretful and somewhat dismissive of the incendiary, provocative and defining nature of Radicalesbians as too defined by collectivity and not enough by a focus on direct action.

Though the group only lasted a few years, it reimagined lesbian activism by centering it for lesbians only. As the groundbreaking manifesto “The Woman-Identified Woman” states in its searing opening salvo: “What is a lesbian? A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion.”

Today — 53 years after it was written and delivered to that auditorium of 400 stunned feminists who had never experienced a political zap — it remains an extraordinary political document.

As a founding mission statement for Radicalesbians, “The Woman-Identified Woman” lays bare all that was missing from the more tame, established and semi-closeted Daughters of Bilitis. It also incorporated the newly defined precepts of a feminism unafraid to take on men, the patriarchy and most definingly, compulsive heterosexuality as a stultifying and oppressive regime that disallowed women their full agency.

The treatise states: “It should first be understood that lesbianism, like male homosexuality, is a category of behavior possible only in a sexist society characterized by rigid sex roles and dominated by male supremacy. Those sex roles dehumanize women by defining us as a supportive/serving caste in relation to the master caste of men, and emotionally cripple men by demanding that they be alienated from their own bodies and emotions in order to perform their economic/political/military functions effectively.”

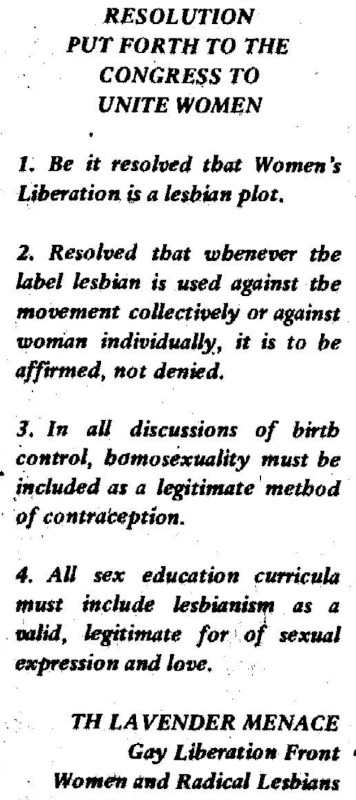

In the Lavender Menace action at the Congress, the resolution passed at the end had these four points:

“1. Be it resolved that Women’s Liberation is a lesbian plot.

2. Resolved that whenever the label lesbian is used against the movement collectively or against women individually, it is to be affirmed, not denied.

3. In all discussions of birth control, homosexuality must be included as a legitimate method of contraception.

4. All sex education curricula must include lesbianism as a valid, legitimate form of sexual expression and love.”

As Radicalesbians set out to create their own movement, they worked hard to avoid the problems they had experienced in other groups, as detailed by Jay, Shumsky and Brown. “They wanted to develop an organization that would nurture each member, encourage equal participation, and discourage patriarchal ‘leadership hierarchies’ that would allow individual women to exert undue influence on the group.”

That concept, writes Shumsky, was also a death knell. “Meetings became more directionless, awkward, and unfulfilling. Radicalesbians gradually abandoned all the forms the agenda so gloriously extolled. Each week, instead of fifty or sixty women, only fifteen or twenty would appear, many of these new women coming for the first time, never to be seen again — they probably wondered what the desultory, unfocused meeting was all about.”

Shumsky says, “Radicalesbians had been trying to fit a life force into an arbitrary form,” but also explains that the Philadelphia chapter of Radicalesbians had bypassed these issues entirely and focused on the meaningful connections between and among women in consciousness-raising groups and small direct actions.

What remains of Radicalesbians over time, now that many of the founding members of the New York and Philadelphia chapters have died, is that initial action and that extraordinary treatise. The women who founded Radicalesbians and the spirit behind the group were dedicated to the principle that lesbians deserve their own space, their own identity and their own movement: lesbians could not and must not be adjuncts to gay men or closeted handmaidens to heterosexual women.

Radicalesbians created and spawned the innovative concept of a feminism devoid of patriarchal control and which allowed bodily and hierarchical autonomy was a positive, purposeful concept and action in the growth and expansion of second-wave feminism that led to third-wave feminism and a more accepting understanding of the needs and oppression of lesbian and queer women.As Eleanor Medhurst writes in her essay “Lesbian Rebellion and the Lavender Menace,” “Lesbians were excluded from the Second Congress to Unite Women in 1970, but they made space for themselves anyway. Lesbian issues met feminist issues and realized that they had more in common than that which divided them.”