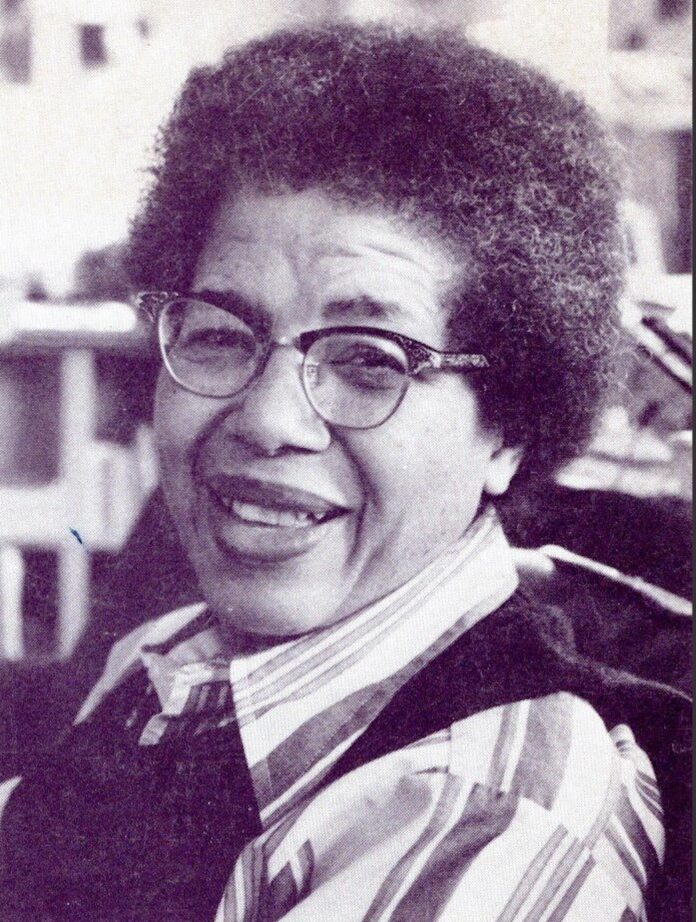

Anita Cornwell passed away May 27 in Germantown “surrounded by the compassionate women who cared for her,” her literary executor, Briona Simone Jones, said. Cornwell, a well-known writer and activist, was a fixture in the lesbian feminist community in Philadelphia for decades. She was 99 years old and was living at Wesley Enhanced Living Center at Stapeley.

Cornwell was one of the first black lesbian activists many Philadelphia LGBTQ people knew of in the early years pre-Stonewall. She consistently showed up at LGBTQ events over several decades, often wearing purple and lavender, colors she said were signature lesbian colors. Cornwell was a member of Daughters of Bilitis and one of the founding members of the Philadelphia chapter of Radicalesbians.

The first out Black lesbian to publish her work in the mainstream as well as lesbian publications, Cornwell’s early work appeared in The Ladder and Negro Digest in the 1950s where she was openly identified as a lesbian — a groundbreaking act at that time. In 1983, Naiad Press published her work “Black Lesbian in White America.”

Sinister Wisdom, the lesbian literary and arts journal, has long featured Cornwell’s work and is republishing it as part of their Sapphic Classics series. Editor Julie R. Enszer told PGN, “I am enormously grateful to Cornwell for her work and for how it contributed to my thinking and my actions in the world. She is a writer who brought lesbian communities into deep and meaningful conversations about racism, sexism, homophobia, and classism.”

Cornwell’s longtime friend, Philadelphia writer Janet Mason, shared several of her blog and podcast posts on Cornwell. She told PGN, “When I reflect back on my long friendship with Anita, I recall that she taught me many things. Most of all, she was the embodiment of what it meant to be a writer — to take yourself seriously and most of all to show up and to keep on doing so.”

Mason said, “To paraphrase a remark that Anita made to me at a writing conference, the publishing world can be hard, but stick with it — eventually the editors at presses change and you can submit to the new ones.”

Tommi Avicolli Mecca, historian, archivist and writer in Philadelphia for many years before relocating to San Francisco, told PGN, “I’m saddened to hear of Anita’s death. She was an amazing writer, an important voice — such a powerful voice in the community. I was blessed to know her and hear her read. I hope her work lives on forever.”

It was in The Ladder, the publication of the first lesbian activist organization in the U.S., Daughters of Bilitis, that Cornwell first wrote about her experiences in Greenwich Village in the 1940s and 1950s, where she was the first Black lesbian to write openly for the publication. (Lorraine Hansberry wrote for The Ladder under a pseudonym.)

In her mainstream work for newspapers and magazines, Negro Digest boldly referred to Cornwell as a lesbian — unheard of in the 1950s.

In “Black Lesbian in White America,” widely noted as the first collection of essays by a Black lesbian, Cornwell writes, “During that time, about the only visible Gays were the swaggering butch and the swishing faggot, who were about as welcome in that ‘genteel’ climate of the fifties as a grizzly bear. In fact, I do believe the bear would have had a decided advantage.” She said of lesbians of her era, “We of the fifties (and the forties and on back to when) not only had to operate from the closet but, worse yet, most of us seemed to exist in a vacuum.”

A defiantly staunch feminist and, for a period of time, a lesbian separatist, Cornwell infused her politics into every local and national group to which she belonged. Hers were fierce and seductive politics, framed in a folksy, witty, charming banter that casually insinuated itself into the conversation until everyone was listening only to Anita Cornwell.

No one else was talking, and so she told the complex tale of being a Black lesbian in white America. Cornwell was, above all, a raconteur. She told stories from every chapter of her life and every decade of gay and lesbian life. She was a chronicler of her time. And when she spoke, everyone listened.

The population of Greenwood, South Carolina was only 8,700 in 1923, the year Cornwell was born there. A third of the population was Black, but it was the height of Jim Crow laws and, as Cornwell recounted in interviews, it was a time of tremendous poverty fueled by racism “when integration was a term seen only in the dictionary.”

She told Philadelphia historian Marc Stein that there would have been no knowledge of gayness in that environment — that “it was like another century.” Cornwell said she first became aware she was attracted to women in her teens, but didn’t come out until she met other lesbians after college in the late 1940s.

Her family moved to Yeadon, then Philadelphia, when Cornwell was 16 — after she had attended the New York World’s Fair in 1939 with her grandmother.

After graduating with a journalism degree from Temple University in 1948, Cornwell worked for local area newspapers, including the Philadelphia Tribune and the Bulletin. She wrote poetry and essays and published her work in a range of lesbian and feminist publications from 1950 through the 1980s, among them Feminist Review, Labyrinth, Azalea: A Magazine by Third-World Lesbians and BLACK/OUT — which was published in Philadelphia and edited by Philadelphia gay poet Joe Beam.

As Cornwell explained in an interview with Marc Stein when she was 70, she became involved in lesbian-feminist politics right at the cusp of Stonewall. She said, “Black women have always been feminists. I mean that’s the only way we survived, that we were feminists. See a lot of people think being feminist means you hate men. And straight women hate men more. Most gay women are feminists, to some extent, I think. Well, naturally I was very interested in the women’s movement because that was the only movement that I saw that might include me.”

Philadelphia writer Becky Birtha wrote the foreword to “Black Lesbian in White America.” She notes that the book offers an acute political analysis of both racial and sexual oppressions. Cornwell was writing about what wasn’t yet known. Her book includes an interview with Audre Lorde, who would become the best-known and most prolific Black lesbian feminist essayist of the 20th century.

In her essays, Cornwell elucidated how lesbians must address their internalized misogyny as well as their internalized homophobia. It was a revolutionary theory when she first explored it. She wrote, “The thing I find most disturbing regarding womyn in general is the seeming impossibility of their thinking clearly when it comes time to deal with men. Womyn with advanced university degrees often seem utterly unable to dot an i when they are confronted with the realities of man’s barbaric treatment of womyn. To put it bluntly, I find it absolutely terrifying to see just how effective men have been in eradicating womyn’s sense of self, a condition that seems to prevail in at least 90 percent of all womyn all over this male-infected globe.”

Racism was another crucial issue for Cornwell, and she found it embedded in the bar culture where, she said, “We went to one gay bar, which was called Rusty’s, and it was very prejudiced. I could tell they didn’t want us [Black lesbians] there.”

Cornwell also addresses racism in the feminist movement, but is slightly easier on women. She said, “See, you can’t live in a country that’s racist and not be affected in some manner or other. So naturally they had the same attitudes to some extent that the regular society had. But also there was some willingness to try to change to some extent. Of course there were varying degrees of success and non-success.”

As Enszer notes: “I first read “Black Lesbian in White America” in the early 1990s when I was living and working in Detroit. In the book, Cornwell invited me into a conversation with other African-American lesbians about the material conditions of our lives. It is a conversation that I have continued in the subsequent years and decades.”

For Cornwell, the focus of her activism always included women and lesbians. She lived most of her years in West Philly, on the outskirts of the Penn campus in a series of communes with other women. She spent time at the Women’s Center and read her poetry and fiction throughout the city.

Enszer told PGN, ““Black Lesbian in White America,” captures many elements of what I appreciate about Cornwell’s work. The book contains a series of deeply personal autobiographical vignettes that intimate some of the interior despair of young adulthood for lesbians seeking to find others like them in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, a scintillating portrait of Audre Lorde, written after the two of them spent time together for an interview, and some of Cornwell’s clear-eyed assessments of the effects of racism in the women’s movement and the sexism that Black women faced in relationships with men.”

She said, “The emotional registers of the collection are varied; Cornwell writes with both the clarity of a journalist and the heart of a poet. Understanding Cornwell’s work — and the work of her contemporaries including Ann Allen Shockley, Audre Lorde, Pat Parker, Red Jordan Arobateau — is vital to understanding the lesbian past as a multicultural, politically engaged formation.”

Cornwell suffered from dementia for nearly 20 years, during which time she lived at Stapeley. Another longtime lesbian activist, Ahavia Lavana, lived in the same nursing home as Cornwell until she died in November 2018.

In 2011, Lavana posted on Cornwell’s Amazon page, “I have known the author for many years. Anita no longer remembers that she wrote this book, but I got her to sign my copy. She said she had never done this before. But I told her that she had signed many books. So she wrote her name and then thought a moment. Then she said ‘I’m a celebrate!’ I told her that she most certainly is a celebrate and gave her a hug. When she sees me, she knows I know her and smiles at me. Which delights me as mostly she just sits. This is a wonderful book and should be read by any feminist and lesbian.”

In a statement, Jones wrote, “Anita will be remembered as a generous, tenacious, and passionate lover, friend, teacher, mentor, writer, and scholar. She leaves behind her devoted friends and chosen family, literary executor, Briona Simone Jones, and a community of Black lesbians and readers whose lives were transformed by her radical vision and her purposed writing.”

Jones included this 1981 quote from Cornwell: “If I might be so bold as to express a heartfelt wish for the future, it would be that all Sisters of all races, creeds, colors, and sexual persuasions might realize the folly of fighting amongst ourselves and band together to confront our common enemy, who continues to wage an unrelenting war against all of us.”

An online memorial will be hosted by Briona Simone Jones and SinisterWisdom.org on Thursday, September 21, 2023, at 7:00 p.m. (EST). An in-person memorial will be held at William Way LGBT Community Center in Philadelphia on Saturday, September 30, 2023, at 2:00 p.m. (EST).