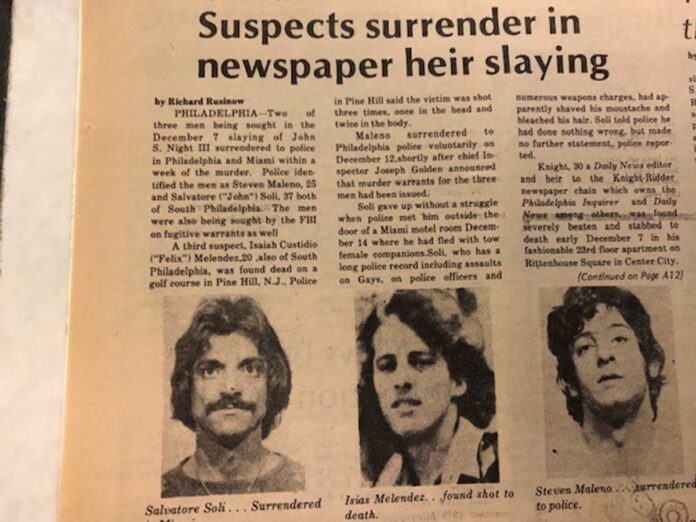

On December 7, 1975, John S. Knight III, former editor of the Philadelphia Daily News and the heir to the Knight-Ridder newspaper chain, was murdered in his home. Less than a week later, two suspects, Salvatore Soli and Steven Maleno, were apprehended. A third suspect, Felix Melendez, was found shot to death in New Jersey.

How the police handled the investigation up until the perpetrators’ capture, though, is where things got complicated. In their publicity of the case, the Philadelphia Police Department “leaked” to the press that Knight, and possibly his assailants, was “gay or bisexual.”

Police used evidence obtained from a search of Knight’s apartment and from witness testimony to conduct what PGN writer Richard Rusinow described as “the most intensive” police investigation ever to occur in Philadelphia’s gay bars and the surrounding neighborhood. The media, aside from the Daily News and the Inquirer (both owned by Knight-Ridder at the time), took the notes fed to them by the police and ran sensationalistic, gay-baiting headlines, including “Gay World Searched for Heir’s Killers” and “‘Kinky’ Aspects of Slaying Vexes Papers,” which were both printed in the Philadelphia Bulletin.

Around 60 men, most of whom were gay, were brought in and questioned in connection to the murder. Several told PGN at the time that they did not know Knight and had no idea why they were brought in. Other gay men were stopped by police while walking down Spruce Street and shown sketches of the suspects. PGN Publisher Mark Segal said in the January 1976 issue of PGN “Never have the police given out so much information about a person’s personal life. The murder victim is being persecuted and the gay community is the pawn in the whole thing.”

One of the some 60 men who were brought in for questioning was Dennis Rubini. Rubini detailed his ordeal in an August 1976 article in PGN. A few days after the investigation began, Rubini had gone onto a TV talk show and been flagged by a staff member as resembling the police artist’s renderings of the assailants. The staff member alerted police and Rubini was escorted from his apartment to the PPD’s “Roundhouse” headquarters.

“Let me hasten to say,” Rubini wrote, “that most of the detectives displayed exemplary behavior. Indeed, if you are going to be investigated by the police in Philadelphia, you will be far better treated if you’re brought in on suspicion of murder than if the vice squad entraps you for some victimless crime. People suspected of ‘murder one’ are treated with respect.”

Rubini was then given a polygraph test. The questions began with “Do you live in America?” and peaked with “Did you murder John S. Knight III?” However, the police also asked “Do you commit perverted sexual acts?”

Rubini commented in his article in PGN that he objected to the question as irrelevant to the murder investigation and an invasion of privacy.

“Half a million people in the metropolitan area are gay,” Rubini told police, “and they come from all walks of life. Some even play for the Flyers: why don’t you question them?”

Despite the police hostility Rubini was released after passing the polygraph.

A few days later, the two assailants were captured. The entire exercise — gay-baiting the media, questioning people solely based on their sexuality, forcing those brought in to answer invasive personal questions unrelated to the case — was not uncommon for police at the time. As many longtime gay activists have said, gay people in 1976 were assumed to be bad solely because of their sexuality. One example of this mindset was during the trial of Salvatore Soli, when the defense used homophobic language to describe Knight.

Rubini, who attended the trial, wrote in PGN at the time, “I asked [District Attorney] Fitzpatrick why he wasn’t objecting to [the defense’s] repeated use of such terms as ‘perverted’ and ‘deviant.’ (Legally they could be considered “characterizing” and thus inadmissible.) He got very hot under the collar and told me that he did not want to turn the trial into a gay consciousness-raising session…the D.A. seemed very nervous around me after our conversation, perhaps fearing that some outburst from the gay community would ruin his strategy for getting a first degree murder conviction.”

Ultimately, both Soli and Maleno were both convicted of Knight’s murder. The way in which the incident was handled, however, is an unfortunate, yet unsurprising example of how the gay community was unfairly judged and treated in the 1970s.