“When we were kids, we all thought we were the only Somali person in the world who felt the way we felt and believed the way we believed,” said Mushtaq Abdullahi, a young Somali lesbian woman living in Philadelphia, and one of four administrators of the online group LGBTQ Somalis.

Public LGBTQ+ Somali representation is virtually nonexistent, she explained, which is why she and her friend Yunis Karone had conversations about starting a group specifically for LGBTQ Somalis around 2017. But it wasn’t until April 3 of this year, that Abdullahi officially launched the group, with Karone, Jonas Mali and Abdimaroodi as co-founders.

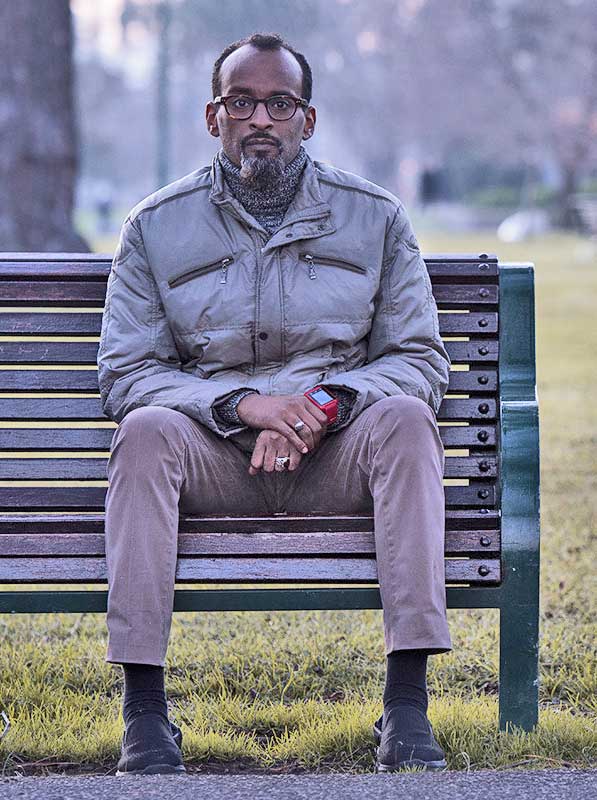

While Abdullahi is a Philly local, Abdimaroodi resides in Chicago, Mali lives in Columbus, Ohio and Karone currently lives in Helsinki, Finland, though he has also called Nairobi and London home also.

Their impetus for starting the group was fueled by “that desire to not let another Somali kid go through that, where they feel like they’re literally the only person in their family or community that’s attracted to the same gender, or that they do not [identify with] the gender that they were assigned to,” Abdullahi said. “It was that desire to represent the community and tell the world, ‘we exist, we’re here.’”

The group offers a variety of virtual events and ways to engage with each other, including a weekly live stream called “Sheeko Sheeko,” where community members can ask the admins questions, and the admins provide advice. They have also done interviews with LGBTQ Somali folks, including a discussion with Imam Nur Warsame, Australia’s first openly gay Imam.

“When we interviewed the Imam, a lot of people really liked it because Islam is an important religion in our community,” Abdullahi said. “A lot of people liked hearing someone tell them, ‘queerness and the religion Islam are not mutually exclusive.’” The group hopes to hold more virtual events where speakers address the intersection of Islam and queerness.

Other of the LGBTQ Somalis group endeavors include a blog that Karone created called “Duumo Diaries,” where members can share their personal stories about queerness, and another weekly event called “Kiki with Maroodi.”

“Kiki with Maroodi is basically the fun part,” Abdimaroodi said. “I have guests, we just talk and listen to music. Sometimes it gets deep, but, all in all, it’s mostly fun.”

Twice a week, the group admins post submissions from community members, in which they introduce themselves, share their story and discuss their work. Eventually, the group would like to host in-person workshops, but members’ disparate locations may complicate those plans, Abdullahi said.

Not only does the LGBTQ Somalis group provide programming and post content in English, but Mali translates the group’s social media posts into Somali, so Somali-speaking members can engage as well. Karone encourages members to submit their blogs in Somali, many of which receive more views than the English-language blog posts.

“It just shows you that Somalis back home or people who don’t speak English need stories like this,” Karone said.

Mali, having lived in Mogadishu, Somalia for roughly three years, discussed his experience living as a queer man in a country that criminalizes homosexuality and other LGBTQ identities. Somalis and Somali residents who are caught engaging in queer activities can face prison time and even the death penalty.

“Once I started getting used to the area, the language, the people and the culture, that’s when I started… to discover underground queer communities,” Mali said. “I started to breathe again. At the same time, you can’t really do anything because the whole country is corrupt, and once you get caught with any ‘sinful act,’ it could be very dangerous. Pretty much people have tried to stay underground and they’re very discreet about what they do for safety purposes.”

Karone explained that living as an openly queer person in Nairobi is similar, though not quite as dangerous. “You can still get [time in jail] and if people get to you, you can be stoned to death,” Karone said. “So everything pretty much is underground.”

In its two months of existence, the LGBTQ Somalis group has received substantial engagement and support from their peers.

“You would think in 2020 we would no longer have people still thinking they’re the only [queer Somali] in the world, but in our community, it’s very much a real thing where people feel alone,” Abdullahi said. “We’ve had so many messages from people saying, ‘Wow, I thought I was the only queer Somali until I saw you guys; thank you for that.’”

Abdullahi is working on turning the group into a nonprofit organization to provide resources for Somali LGBTQ community members. “If a queer or trans Somali person decides to be open, they may lose their family, they may be kicked out or they may even be sent home,” she said.

“We have this phrase called ‘Dhaqan Celis,’ [which] roughly translates to ‘returning to the culture.’ But what it means is, Somali parents sending their kids who grew up in the west back home because they feel like their kids were too westernized. Oftentimes, that happens to queer and trans kids. [We want to] create that nonprofit and get funding so we can make sure a kid is safe, or if a kid feels like they’re in danger of being sent back home, we can ask, what can we do as a community to make sure that that doesn’t happen?”

Check out the LGBTQ Somalis group on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lgbtqsomalis/ and Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lgbtq_somalis/