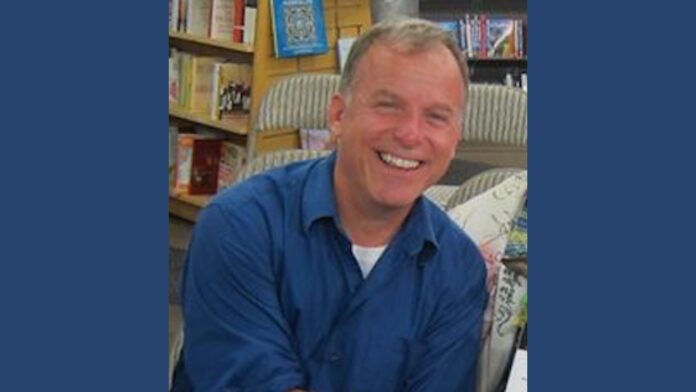

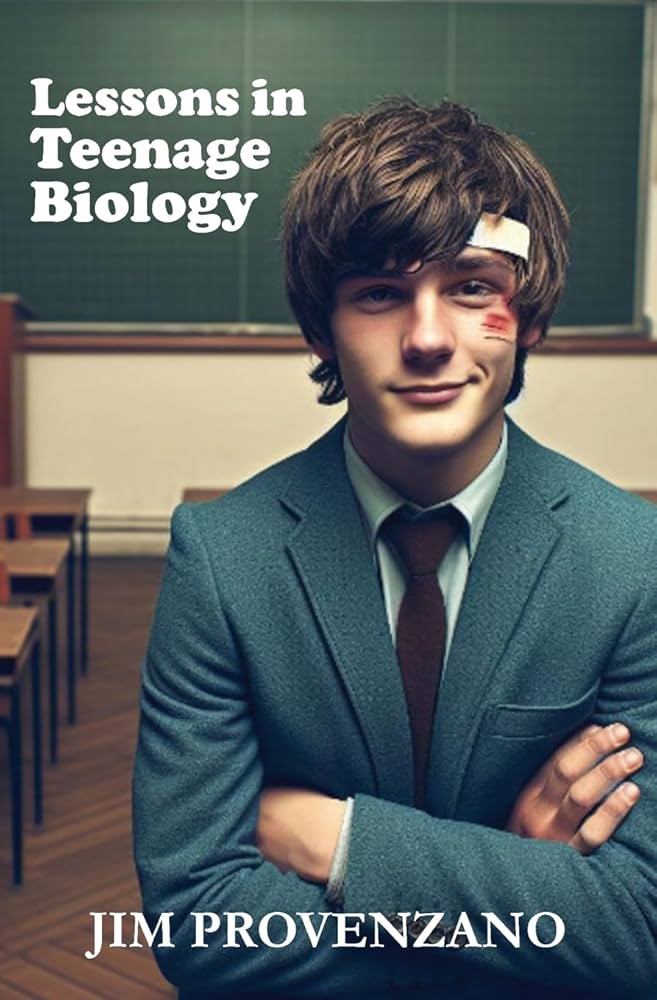

YA fiction has come a long way since many of us were, well, young adults. I’m not just talking about maniacal TERF J.K. Rowling’s inexplicably popular fantasy novel series either. The presence and representation of queer characters in books, including Alice Oseman’s “Heartstopper” series, is central and necessary. This is something of which gay journalist and Lambda Literary Award-winning novelist Jim Provenzano is keenly aware in his debut YA novella, “Lessons in Teenage Biology” (Myrmidude Press, 2024). While set in the late 1970s, the story of queer high school student Tom Mollicelli’s daily struggles could just as easily be taking place today. Subjects such as bullying, secret crushes, and family situations, still have the resonance they did almost 50 years ago (or more). Jim was gracious enough to make time for an interview during Pride month 2024.

If I’ve done my research thoroughly, “Lessons in Teenage Biology” is your first novella. Do you foresee writing additional novellas about Tom Mollicelli?

I’ve only written one novel sequel, and that was “Message of Love,” the sequel to my fourth novel, “Every Time I Think of You.” It wasn’t expected, but by the time I finished it, I had already had a bunch of side notes that developed into the sequel. Several advance readers said they wanted more. But I’m not sure about that because I originally wrote this back in 1986. To write more would be kind of impersonating the voice that I had at the time. I’ve done that before, but I’m not sure I want to do that this time.

I’m guessing that you’ve been out of high school for a while. However, you’ve succeeded in giving the setting gravitas and authenticity. What are the rewards and challenges for you when it comes to writing about the 1970s?

I feel a kind of responsibility to describe that era because those who experienced that are part of an elder generation that needs to tell their stories. It’s also a very rich time in terms of music, fashion, good or bad, and just the whole era of it was innocent in some ways. And since the 1970s are now 40 years ago, I like to presume that it could be considered historical fiction [laughs].

The 1970s setting of “Lessons in Teenage Biology” made me think about the YA books being read during the 1970s, including those by Paul Zindel, Judy Blume, and S.E. Hinton, among others. Do you have a favorite YA author from this period?

I was a voracious reader for as far as I can remember, including getting stickers from the public library for the amount of books I read, or going to the Scholastic Book Fairs as a teen. It’s kind of obvious, but JD Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye” just struck a chord for me at the time.

Each of the chapters uses a biological term as its title. Was that something you planned from the start, or did it come later?

As I said, I wrote this in 1986. The first draft was just a flurry of writing on a manual typewriter with paper that I taped together to try to make a scroll like Jack Kerouac did. He was, of course, a big influence for me back in college with my early scribblings. The biological terms came later when I realized I wanted it divided into chapters instead of being a big run-on as the original was written.

I wanted a title that was clearly Young Adult but also clever, like a textbook. The original title was “Little Volcanoes,” which is a reference to acne. But in looking up other titles with volcanoes, they were literally about volcanoes, so I didn’t want to make that mistake. Of course, Bonnie Garmus’ book (and TV series) “Lessons in Chemistry” was a big inspiration for the title. It has a double meaning and I like that.

Bullying, which I think has been around since the beginning of time, appears in the book, prominently represented by the vicious Joe Briggs. Did you experience bullying when you were a teen?

Well, a lot of this is based on actual experiences and yes, I did actually get bullied by a guy in school which led to a fight, and then it was broken up by my late sister. It’s really all an homage to her. The sister character is basically her, too.

I appreciated the way you wrote about religion in the book, particularly at the opening of the “Metaphase” chapter. It serves as a reminder of the way religious fanaticism has been infiltrating public schools for years.

Yes, there were a lot of well-intentioned Christian schoolmates who tried to get me to go to church meetings. Mostly I just went because I had a crush on the guy, but it never took. And yes, they would slip those awful Chick Comics in your locker slats, as if a tiny comic book would convert us [laughs]!

In the second and fifth chapters of the book, you write about Tom shoplifting a “Playgirl” magazine, which was a kind of rite of passage for a generation of gay men.

I think at that time teenagers didn’t have access to gay pornography, and “Playgirl” was so commonly found in mall bookstores. My mom even had a couple copies at one time, and I would sneak into her bedside dresser to get a peek. When I started shoplifting, I would hide them up in the attic. But my brother found one once and it was very embarrassing.

Writing about sex in a YA book seems like a big responsibility. You handle it with ease, including the subjects of masturbation, blow jobs, homoeroticism, when “boners bumped,” and, of course, the last page! What are the challenges and rewards of writing about sex?

Writing about sex can either be intentionally erotic or comic. And I tried to do both. The main point of pornography is the plumbing, I guess. The main point of literary descriptions is that you describe everything else that’s going on, including the sex.

I don’t know if you were thinking about book banning while you were writing “Lessons in Teenage Biology,” but if you were, what would it mean to you if your novella was banned?

I’ve joked with other fellow authors that we would love to be banned for publicity purposes, but it’s actually a serious issue. Thousands of books have been stolen or taken from schools and public libraries by right wingers, and their efforts often backfire. There are a lot of groups that are fighting to keep books on shelves and to defend librarians and libraries. It’s a constant struggle. But being a small, mostly self-published author, I’m just happy to get in any public library. My books are in 83 different libraries around the U.S., so it’s really great to know that they’re there.

If there was a movie version of “Lessons in Teenage Biology,” who would you like to see as Tom? Who as Chuck?

Actually, I’m not very well informed about young actors today, except the “Heartstopper” guys. As long as the actors were comfortable playing the roles, I’d be happy. Whoever played Chuck would have to be beguiling and charming. Whoever played Tom would have to be a bit naïve; clever, but not completely all there.

A long time ago, I had a literary agent for my first novel, and a bite from a film producer for “Pins.” Of course, it never panned out, and I was led by the nose for a long time that it might happen. So, I’m not very enthusiastic about fantasizing about film adaptations.

The best success I had was being asked to write a stage adaptation of “Pins,” which was done here in San Francisco at New Conservatory Theatre Center in 2002. That was a great experience, because some of the actors were just perfect and it had a successful run. I’m certainly open to film adaptations, and I have a few incomplete screenplays, but I don’t get my hopes up. I’d just like people to read my books and imagine the characters on their own.