Diana Rodriguez, who grew up in Jersey City, often met her uncle, Tony, in New York for lunch. They typically ate near 23rd St. — so she wasn’t expecting such a drastic change of location when one day he told her to meet him in Greenwich Village, giving her the address to the site of the historic Stonewall Inn.

Rodriguez’s uncle used Stonewall as a way of acknowledging what was unspoken between the two of them — that they were both gay.

“It was his way of saying, ‘There are people like you out there, and I’m one of them,’” explained Rodriguez, who is now the founder and CEO of Pride Live — the nonprofit spearheading the new Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center, which opened June 28, in partnership with the National Park Service (NPS).

The site will be honored as a national monument with a visitor’s center as part of the NPS, a designation that is deeply meaningful to Rodriguez and her spouse, Ann, who often road trip to national parks across the country. But the site, while important to national history, will always hold personal significance to Rodriguez.

Her uncle Tony, a Vietnam veteran, died just a few months after sharing that lunchtime moment with her on May 9, 1989.

“When his army unit and his colleagues found out he died of AIDS, nobody came to his service,” she said.

To honor his legacy and the lives of others lost to HIV/AIDS, Rodriguez will display a flag used at his funeral in the new visitor’s center.

The exhibits use storytelling to highlight the experiences of people in the Stonewall generation and share information about the bar, the rebellion, the neighborhood, and activism of that time — aiming to help visitors develop a more human connection with the history. For those who can’t travel, resources will also be available online in the coming months.

“Our stories in our history and in the community are still primarily passed down [through] word of mouth,” Rodriguez said, underlining that most schools and curriculums don’t mention Stonewall. Pride Live is capitalizing on that connection to oral histories by helping queer elders share their memories in recordings that will be featured in the space.

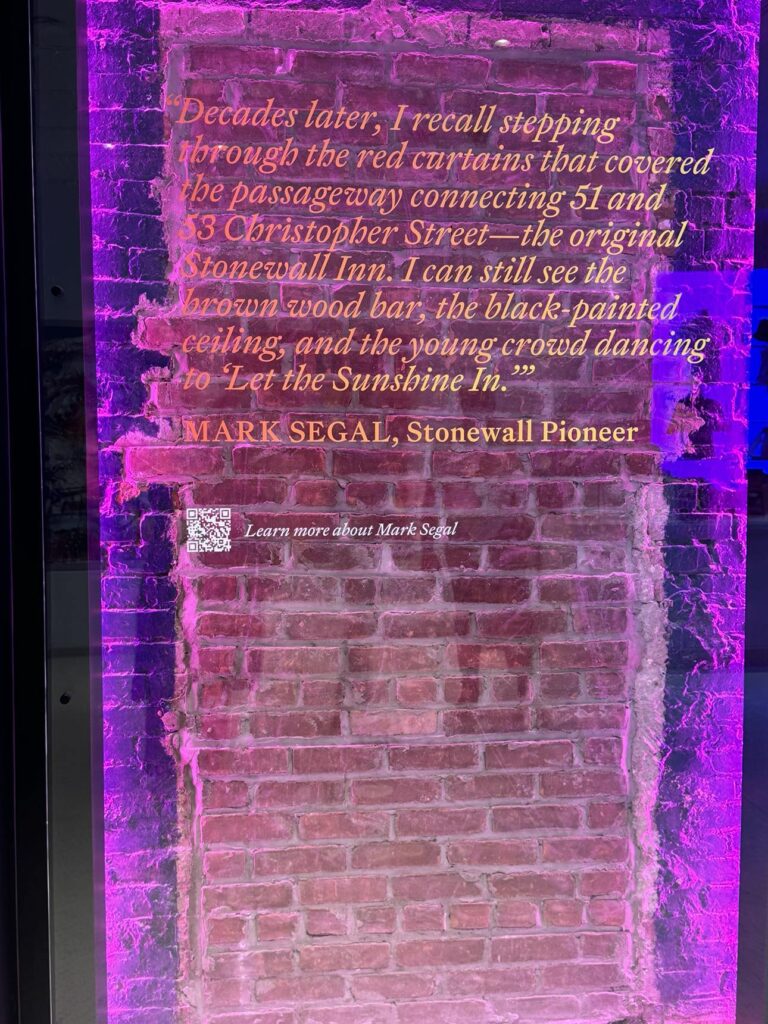

Rodriguez said that many LGBTQ+ people can name Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson as notable figures associated with Stonewall, so she wanted to use the visitor’s center to hone in on lesser known people and stories. She worked closely with activists of that time period — including PGN’s Mark Segal, who participated in the Stonewall rebellion and subsequent activism — to ensure that the monument would include more perspectives.

At a preview event offering Philadelphia media professionals and LGBTQ+ leaders a sneak peek of the space, Segal helped those gathered imagine what it looked like on the night of the historic rebellion. He gestured to the museum’s new theater — a flexible-use room with rows of chairs and a projector. It used to be a dance floor.

He showed where the bar once stood, which is now outlined on the floor. Just a few feet away, coins sit atop a jukebox ready for today’s visitors to select their favorite hits of the time period — filling the space with music again. A former passageway between the visitor’s center and the still-active Stonewall Inn next door — which connected the buildings as a single bar in 1969 — is highlighted on the wall.

At the preview, Segal noted the community he met after moving to New York City from Philadelphia in 1969.

“Every night, we walked up and down [Christopher] street— with a good deal of people you’ll see on these walls. These are my brothers and sisters,” Segal said during his speech. “Late at night, we’d come here — Stonewall. It was safe in here.”

In addition to learning about LGBTQ+ history at the visitor’s center, tourists can spend time in the bar next door — which is still known as the Stonewall Inn — and spend time in the Pride-filled park across the street.

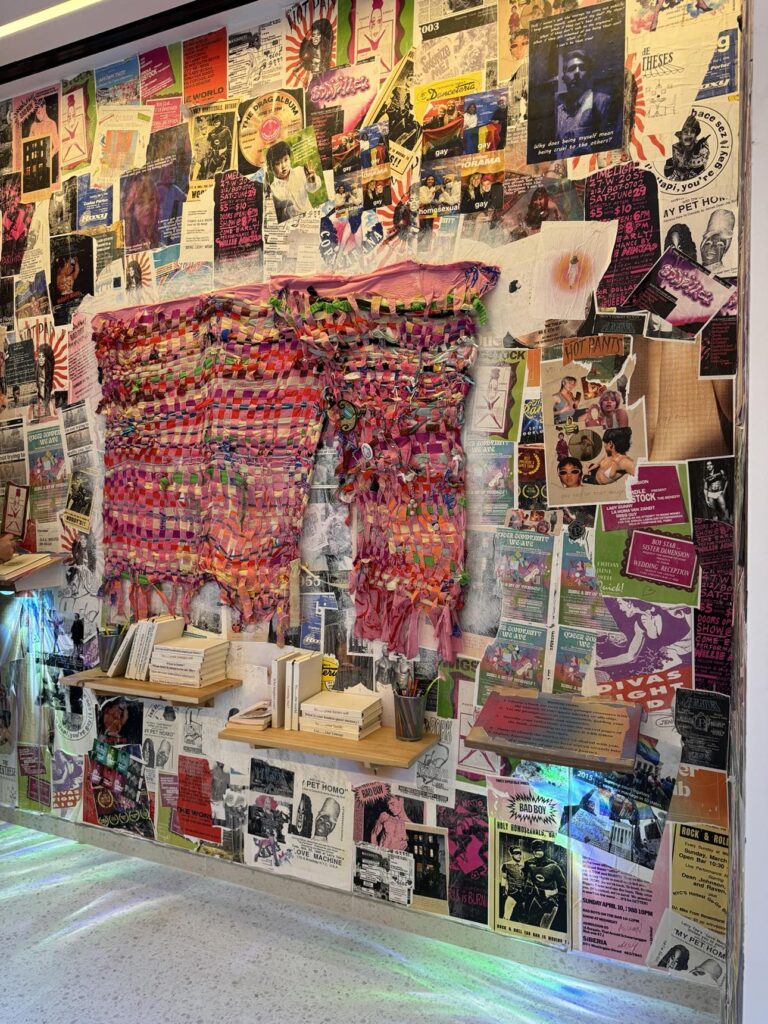

Rodriguez is also interested in bridging the past with the present. Pride Live has developed an exhibit in partnership with Parsons School of Design to feature student creations. Rodriguez explained that cohorts will take a course about Stonewall and its legacy and develop their own contribution to the visitor’s center that will rotate each year. The class is given only the dimensions of the space where the art will be displayed to avoid influencing outcomes or stifling creativity. Rodriguez hopes that each year, the art will reflect the very specific experiences of young people in that given moment of time.

A colorful, weaved curtain hangs at the center of the inaugural exhibit. A collage of posters and images that reflect queer community and experiences covers the walls of the display. Journals with just a few notes await more visitors who are invited to read what others have written and add their own responses to various prompts.

Pride Live is also partnering with Visit Philadelphia to help travelers establish a connection between cities, which Segal noted were both important communities in early efforts to seek LGBTQ+ rights.

“We want you to come visit the visitor’s center then go to Philadelphia to learn about their history,” Rodriguez said. She hopes to later develop partnerships with other cities across the United States — especially places people don’t typically associate with the movement which were also making strides during the Stonewall era.

“In the United States, where we hold freedom at the top of our list of all of our rights, we want to make sure that Philadelphia remains a place that is friendly and open and inclusive,” said Angela Val, president and CEO of Visit Philadelphia, who noted that some places are moving in the opposite direction lately.

Val pointed out that various shops, community spaces and historic sites exist in Philadelphia for people to learn about LGBTQ+ history. Her dream is for travelers to be welcomed by a tangible exhibit that could serve as a launching point for those who want to continue their learning journey and connect with the LGBTQ+ community while they’re here.

“I really do hope that one day we will have here in Philadelphia something similar to what’s in New York — where people can come to get a continuation of the story, that there would be a place to actually physically go,” Val said, noting that William Way LGBT Community Center could become a hub to host this kind of exhibit.

Val is in the early stages of researching how the city should approach the partnership with Pride Live to create that connection, but those who visit Philadelphia could explore LGBTQ+ history even before Visit Philadelphia launches a formal program.

William Way is already the home of the John J. Wilcox, Jr. Archives, an extensive collection of materials that document and celebrate the history of the LGBTQ+ community in the Philadelphia region. Curators at William Way display three to four exhibitions per year for the public. The Philly LGBT Mapping Project and LGBTQ-specific tours like those offered by Beyond the Bell also provide outlets for exploration.

Val recognized the power of seeing oneself in history when she experienced the 7th Ward Tribute — a project that pays homage to the African American culture and community that is part of Philadelphia’s narrative. As an African American, learning the stories of successful Black people who lived in the buildings she passed all the time helped her feel connected to the space in a different way.

“Having a physical place where you can see yourself and your story and you don’t have to hunt for it, I think is very meaningful,” she underlined.