I first met Audre Lorde at a dinner party in New York City in the early 1980s. I was the plus one of an older woman and the youngest person there by at least 20 years. It was a pinch-me moment: I was in the same room with Audre Lorde and Phyllis Chesler and Betty Dodson, among others, and it wasn’t a classroom or a lecture, but an amazing two-story apartment in New York City. It took my breath away just being in that rarefied atmosphere.

In “A Litany for Survival,” the documentary about Audre Lorde’s life by Black film makers Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson, Audre says, “What I leave behind has a life of its own… I’ve said this about poetry; I’ve said it about children. Well, in a sense I’m saying it about the very artifact of who I have been.”

The artifact of Audre Lorde, the precious little piece I took away with me that night, was like a beautiful shiny object, a talisman. It would stay with me separate and special, apart from her later mentoring me, her teaching me, my learning from her. That first night was magical — I see it so clearly still in my mind’s eye: Audre, right in front of me, asking me to dance. Audre Lorde. Icon.

I can’t explain how it felt to be in her arms. It’s easy to say it was a rush, but it was more than that. Then and in the 30 years since, I felt a deep and visceral connection that was all about Audre and who she was, what her words and personal power meant to me. It stuck with me, that night and forever after. Whatever she had poured out onto me as she held me and talked and laughed in my ear and moved me around the small bit of open floor with her abundance of charisma and charm never left me.

As a 20-something writer, I was ready for the larger-than-life figure of Audre Lorde to imprint me with all her knowledge and all she was willing to tell me about how to live fiercely in the world as she took me in her arms to dance in the living room of that big gorgeous apartment with the floor-to-ceiling windows.

In the decades since her death, we’ve talked about Audre Lorde as a lesbian icon of theory and writing and warrior vision. We talk about her as an historical figure of tremendous depth who taught us with generosity and range. It was that Audre who mentored me from that first night till the last time we talked, when I was living in London and she Berlin. She’s been dead 30 years now, but I can hear her voice as clearly as if she just left the room.

When we talk about Audre, we almost never talk about the cancer.

The night I danced with Audre Lorde she was already missing a breast, having had a mastectomy in 1979, when she’d been diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer was a battle she would fight the rest of her life and it was cancer metastasized to her liver that would kill her in 1992, exactly three months before her 59th birthday.

We didn’t talk about cancer in those days, the early 80s, when Audre was dancing with me, her missing breast a radical symbol of her rejection of the medical industrial complex. There weren’t pink ribbons and races for the cure or October as Breast Cancer Awareness Month. There were just our individual experiences, nearly all of which were kept carefully hidden, a shameful secret.

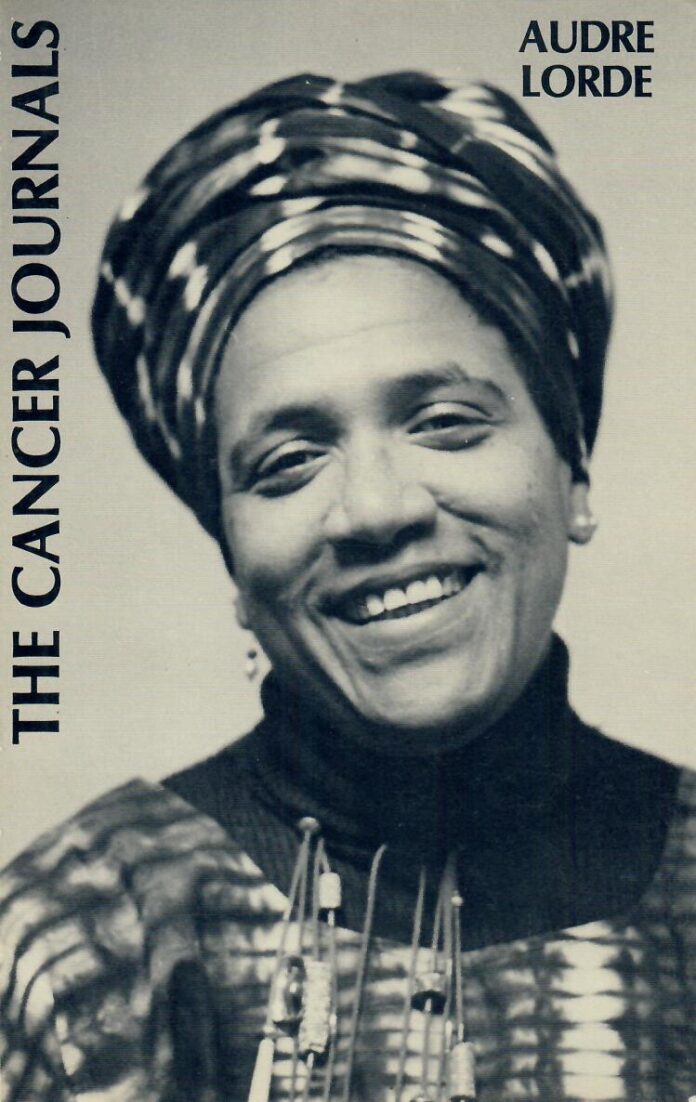

Audre didn’t do secrets. In “The Cancer Journals” she wrote out the experience of cancer — of breast cancer, of a Black lesbian with breast cancer — and it was revolutionary. She wrote about the radical decision not to wear prosthetics post-mastectomy: “Prosthesis offers the empty comfort of ‘Nobody will know the difference.’ But it is that very difference which I wish to affirm, because I have lived it, and survived it, and wish to share that strength with other women. If we are to translate the silence surrounding breast cancer into language and action against this scourge, then the first step is that women with mastectomies must become visible to each other.”

Visibility and breaking silence were constant refrains interwoven throughout Audre’s voluminous work, but they were most pivotal in her discourse on cancer and its impact on her life. She wrote in “The Cancer Journals” that “silence and invisibility go hand in hand with powerlessness.”

Audre wrote so much lesbian feminist theory that her work on cancer is often a footnote rather than a headline. But her speaking out on what it means to have breast cancer, from biopsy to mastectomy and beyond — to be breastless in a society obsessed with breasts — was and still is groundbreaking.

In “The Cancer Journals,” Audre writes about how she was urged to use a prosthetic. She wrote about how Israel’s Defense Minister, Moishe Dayan, who famously wore an eye patch due to losing an eye in World War II, was never told to get rid of the patch and get a glass eye: he was a warrior.

Audre wrote, “Well, women with breast cancer are warriors, also. I have been to war, and still am. So has every woman who has had one or both breasts amputated because of the cancer that is becoming the primary physical scourge of our time. For me, my scars are an honorable reminder that I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2, but the fight is still going on, and I am still a part of it.”

In an interview with the New York Times less than a year before her death about mastectomy and femininity, Audre told the Times, “The social and economic discrimination practiced against women who have breast cancer is not diminished by pretending that mastectomies do not exist.”

It’s impossible to determine the importance these words and ideas had 40 years ago when Audre wrote them. But when I was diagnosed with breast cancer at 26 and again at 28, enduring two lumpectomies and reconstructive surgery, Audre’s words were essential aftercare. The template she laid out for other women in “The Cancer Journals” on how to rage and mourn and forge ahead is perhaps her least appreciated work.

Audre challenges us in “The Cancer Journals” to do the hard work of interrogating our bodies and spirits and how they intersect. She asks: “What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence.”

That cold winter night, snow still on the Manhattan ground, I danced with Audre Lorde. And she taught me, in that moment and in the years to follow, how to think and feel and be in the world, breaking silence, speaking truth to power, and tempering rage with words that propel us forward.