“I wanted to do a political action that was active and visible in the community and not just sit around and discuss political theory,” said Kathy Hogan, who was part of the radical lesbian activism group Dyketactics!. The group was active from 1975-1978.

They described themselves as “lesbian-feminists committed to actions which will raise public consciousness and electrify the imaginations of gay and women’s committees.” But the members of Dyketactics! considered their work intertwined with other groups fighting for civil rights and equality.

Member Paola Bacchetta, now a professor in the department of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in an essay on Dyketactics! that “Most members had come out of prior social movement formations that were not LGBTQI+ specific and remained closely aligned with them or simultaneously within them: black liberation, socialist, communist or anarchist, Native American, student, Puerto Rican independence, and more.”

Like the social movements they fought for, the group’s membership was diverse – they were African American, Chinese, Latinx, mixed race, Native American and of Irish and Italian heritage. As for religion, the women of Dyketactics! were Baptist, Catholic, Buddhist, Jewish and Protestant, and they ranged in age from teens to late twenties.

“We were definitely about promoting lesbian visibility,” said Sherrie Cohen, another member of the group. “We were about taking action against any injustice where we thought our presence would be useful, whether it was from the Church, the state.”

The work of Dyketactics! manifested as involvement in court cases, creative forms of protest, and fighting against their “slumlord” to improve living conditions for their neighbors. To amplify some of their messages, the group sometimes resorted to “graffiti zaps” on billboards, subway walls and ceilings.

The members of Dyketactics! also prioritized “development of a specifically lesbian-and-queer-situated critical analysis of settler colonialism, genocide, slavery, racism and capitalist exploitation,”

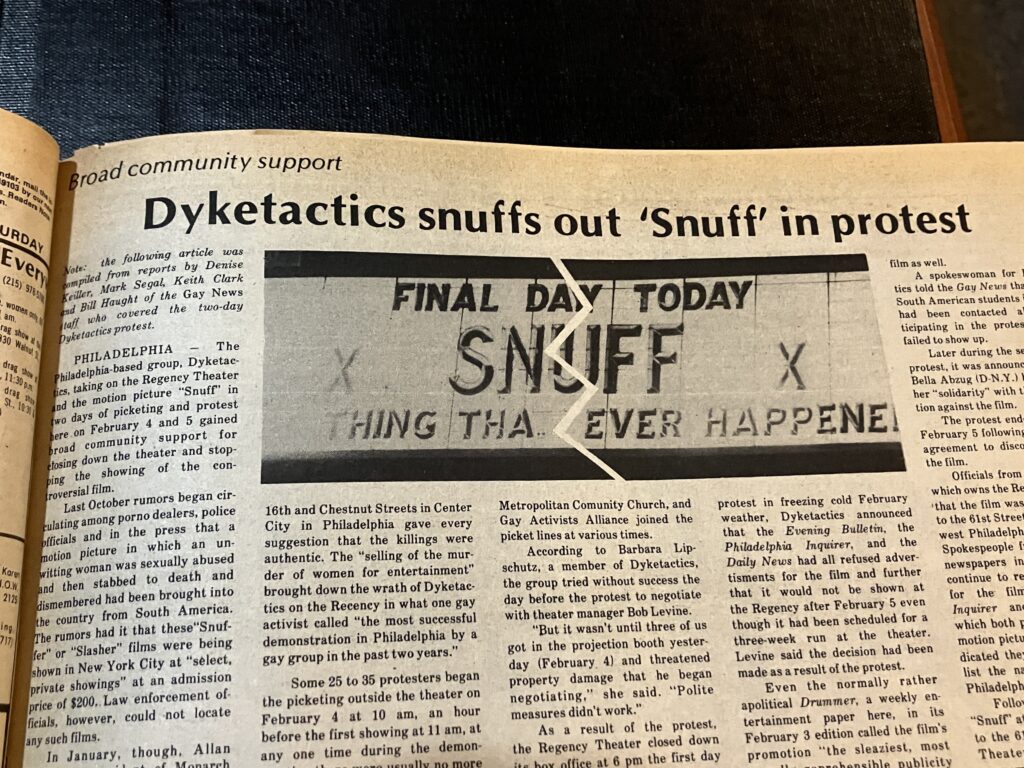

Dyketactics! organized a citywide strike in protest of working women’s double work days, unequal pay and high unemployment rates; they fought back against a local porn theater’s screening of snuff films in which women of color are tortured and killed; and in 1976 they demonstrated at Philadelphia High School for Girls, where the administration pushed back against students who were fighting to have LGBT education included in the school curriculum (not just in health class), and to go to their upcoming prom with their same-gender dates.

The students at Girls High learned that the school had a policy where alumni were allowed to attend prom and bring their dates. Cohen, an alumna of the school, was planning to go to prom and bring a date. But the school administration heard about the gay students’ plan to attend prom, and the school’s vice president told Cohen that there was no such policy.

The school administration’s inaction on the students’ demands inspired the students and members of Dyketactics! to protest.

“I felt that was an important protest to show the school that their actions were heard beyond the halls of the school and the impact of their hostility toward lesbian students,” Cohen said. “That there would be action taken by the community.”

Dyketactics! began in December, 1975, at an action at Philadelphia City Hall. Six queer women, Hogan and Cohen included, made their voices heard at a Philadelphia City Council session in which bill 1275 — which sought to add sexual orientation to the city’s Fair Practices Ordinance — would be voted on in committee.

Phone calls from fellow activists who were planning to attend the Council meeting set things in motion. Before long, Hogan, Cohen and a few of their comrades planned out everything they were going to do at the meeting to speak out for lesbian and gay rights.

In the event that Councilmembers did not vote on the bill, the feminists who made up Dyketactics! planned to stage a kiss-in “to demonstrate the affectional preference for which we were being discriminated against,” Cohen said. At the Council meeting, they held signs that read “You shall never have the comfort of our silence again,” “Lesbians Ignite,” and “Bill 1275, come out.”

“I was going to get a bullhorn and go on top of Billy Penn and say ‘[Councilman] Melvin Greenberg, set a date,’” Hogan said. “That’s how they were blocking the gay rights bill, they wouldn’t set a date to have a hearing for it.”

“We were just upset and irate,” Cohen said. “We were angry dykes who were mad that there was not even going to be a vote on whether or not our community should have legal civil rights in Philadelphia.”

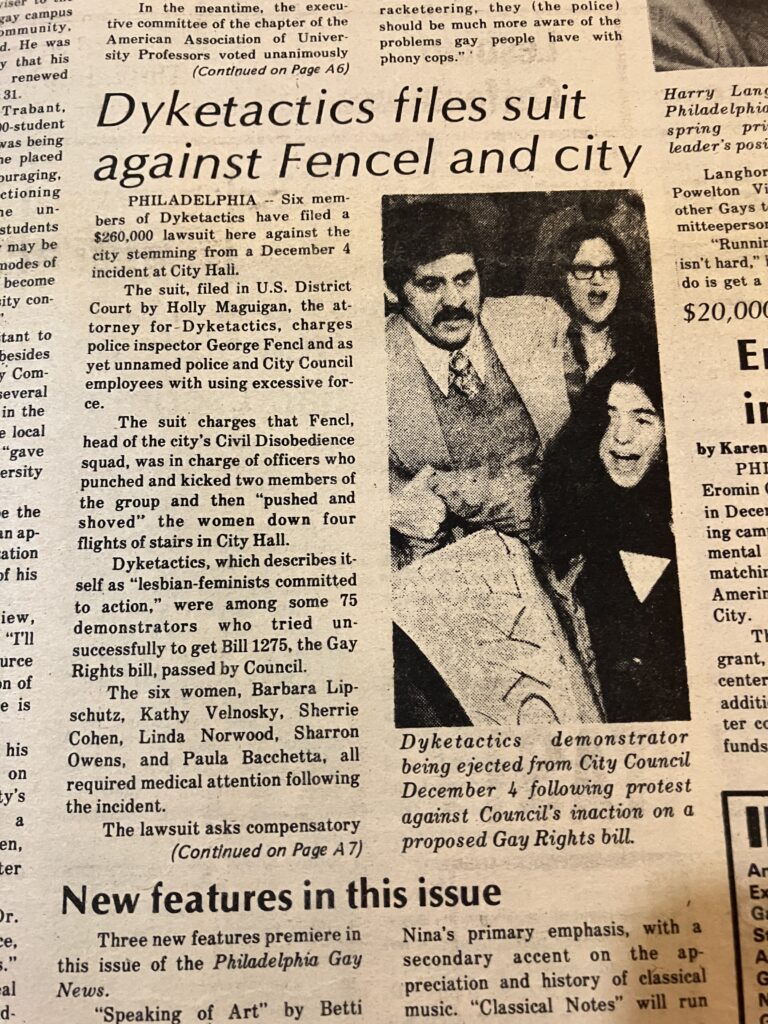

When the members of Dyketactics! began chanting “free bill 1275” in City Council chambers, Council president George X. Schwartz called the police. Before long, the Sergeant at Arms and members of the Civil Affairs Police Unit came into City Council, violently pulled the women from their seats, and dragged some of them by their hair across the floor.

“Some women reported being stomped on or kicked,” Cohen said. “This is still inside City Council as we were being pulled out of the chambers into the hallway. Women were saying they felt injured or bruised, and they were hurting after that.”

After the incident, members of Dyketactics! sued Mayor Frank Rizzo, the City Council Sergeant at Arms, and the Civil Affairs police officers who attacked them. They were the first group in the U.S. to file a federal suit against police brutality aimed expressly at queers, according to Bacchetta’s essay.

Although Dyketactics! did not win the suit, they used the high profile trial that took place to increase mainstream visibility about gay and lesbian people and issues, including the need for sexual orientation to be a protected class.

When the police officers were being questioned in the trial, they were asked whether they were married and about their families. When members of Dyketactics! were questioned, they were asked whether they were lesbians, “as if that was supposed to be an indictment of our humanity,” Cohen said. But the plaintiffs responded with “yes, I am a lesbian and so is 10% of the population of Philadelphia and the U.S.” The women also referenced statistics about crimes against LGBT people, as well as police brutality toward Black and Brown people.

The trial became a “coalitional site” where some of the most radical Philadelphia lesbian and queer activists came together, Bacchetta wrote in her article. Some of those people were Tommi Avicolli Mecca, known for his involvement in the Radical Faerie movement and Gay Liberation Front, and Cei Bell, who worked in the Black trans movement.

Rosalie Davies, who worked on LGBT parental rights cases and founded Custody Action for Lesbian Mothers in 1975, was also involved in Dyketactics! and the police brutality trial.

“Dyketactics was important in a way because this was the most radical extreme we finally went to,” Davies said in a 1993 interview with historian Marc Stein. “It’s very important that, even though you’re going to lose the case, what you’re doing is making a political statement. You’re making a political statement by even calling the word dyke and bringing it into the courtroom.”

Another significant set of protests that Dyketactics! led occurred around the Bicentennial celebrations in Philadelphia in 1976. In addition to participating in mass protests, Dyketactics! organized their own actions. They wanted to orchestrate a large demonstration protesting the perpetuation of homophobia by the church and the state. But because of their upcoming trial at the time and negative image in the eyes of the police, the City refused to grant Dyketactics! a permit. In order to circumvent that, the women formed a subgroup called Dykes for an Amerikan Revolution (DAR).

They drew up a declaration that conveyed their view that America was founded on genocide, subsidized through slavery and preserved through the oppression of women. Such atrocities were those “that have been sanctioned by men’s religion,” according to another of Bacchetta’s articles, “Dyketactics! Notes Toward an Un-Silencing.” The declaration also condemned sexism, homophobia, poverty, racism, imperialism, war and environmental destruction.

For their first part of their three-tiered protest, DAR visited the residence of Cardinal Krol, the Archbishop of the Diocese of Philadelphia at the time. Members of DAR left copies of their declaration in the spokes of Krol’s gate, and spoke through a megaphone about their criticism of the church’s complicity in the state’s support of homophobia and other forms of bigotry on national and global scales.

After that, DAR protested at two churches in Philadelphia’s wealthiest suburbs: the First Presbyterian Church and St. George’s Episcopal Church.

The Bicentennial sermon at the First Presbyterian Church was called “present threats to priceless freedoms,” and included queer people as one of the threats. In response to that, Dyketactics! members performed a guerilla theater outside of the church to an amassing crowd, where they dressed up as personified characters like the patriarchy, the church, the state, and the lesbians.

“Our goal was to make the point that people cannot run away into the suburbs and not feel the impact of what their disinvestment in the city means to the majority of the people of our city,” Cohen said.

By 1978, the members of Dyketactics! could no longer meet on a regular basis, according to Bacchetta, but many of its members continued to do political activism. Cohen became a lawyer, stayed active in LGBTQ organizing, worked with Black liberation movements and unions, ran for City Council twice, and walked on the Longest Walk, in which several hundred Native American people and supporters trekked from San Francisco to Washington D.C. to bring light to threats to Native American rights. Hogan also became a lawyer and did pro bono legal work for people living in poverty. She also amassed and digitized the constitutions of all native nations in the U.S., making them accessible via the internet so the nations could learn from each other.

As for whether she thinks Dyketactics! moved the needle of social change at the time, Hogan said, “I think probably what we did the most good with was moving ourselves. All of the people who were activists that I know of at that time, we sort of radicalized ourselves. We permanently changed how we looked at the world. Regardless of anything we did with the rest of our lives, we brought those attitudes and perspectives with us to whatever work we did and the people that we interacted with in our lives. Hopefully, that had some impact with how we lived our lives.

“Did we actually change anything in the social agenda in the world? I’m not arrogant enough to think that we did, but we sure tried. All you can do as a human being is have a true little heart and have principles and morals, try to leave the world better.”