When you ask about or search for the murders of gay men in Montreal in the ‘90s, it all leads to the podcast “The Village: The Montreal Murders.”

LGBT advocates encouraged me to listen to the CBC podcast hosted by gay French Canadian journalist Francis Plourde. Prior to its release, only a handful of news stories talked about the murders.

“Since the podcast was released, I got quite a few people who lived in Montreal and were in their early 20s when all that happened and many of them had no idea this was happening,” he said. “That’s how segregated things were in Montreal.”

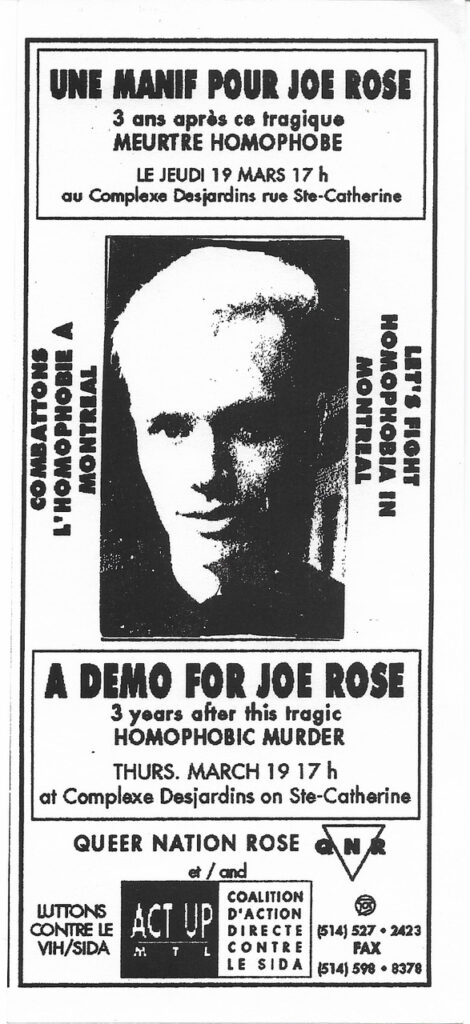

Over seven episodes, the third season of “The Village” investigates the murder of 18 gay men during the HIV/AIDS crisis, starting with the murder of 23-year-old gay activist Joe Rose in March 1989. He was known for his pink hair, “Silence = Death” pin, and snappy comebacks, with a friend telling Plourde that Rose once said, “If you can’t stand the fruits, get out of the orchard.”

Rose was diagnosed with AIDS at age 19 after donating blood, but he never hid his status and his goal was to start a chapter of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in Montreal. He never got the chance.

While riding a bus home to the HIV/AIDS hospice where he was living, four teens yelled homophobic slurs at him, then beat and stabbed him to death. The oldest of the group, a 19-year-old named Patrick Moise, was only sentenced to seven years in prison. The public blamed gang violence because the teens were Black. Others said it was a lack of bus safety. But the LGBT community stood up and said what no one wanted to hear: it was homophobia.

Rose’s story became folklore and the LGBT community in Montreal and beyond rallied for justice, but unfortunately, his murder would not be the last. The same night, Richard Gallant, 28, was found stabbed to death in his home in The Village. Then 16 other gay men were murdered in Montreal between 1989 and 1993.

South Florida Gay News had the chance to talk to Plourde about making “The Village: The Montreal Murders” and bringing to light a piece of Canada’s LGBT history.

This season doesn’t have a single “villain.” How did that complicate things?

For a long time, there were fears that there was a serial killer in Montreal, in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s. Turns out there was one, but that was not the only reason why gay men were dying in The Village in Montreal. So it was a bit of a challenge in terms of, like, so many of those cases were different and in terms of how they happened, the background of the individual. There were things in common, but there were also big, big differences as well.

So in this case it was a challenge, yes, for research and for storytelling. But at the same time, we wanted to do something a bit different with that season. We wanted to look at the broader context of Montreal and what it was to be queer in Montreal in the early ‘90s. So the series became focused on those crimes that happened in Montreal, but it was also about the AIDS crisis that was happening at the same time, which was kind of fueling the homophobia that we saw in Montreal in those days. And we wanted to show that it was also a story about the empowerment of a community, a community rising together.

What response did you get from sources 30 years later?

On one hand, there was this eagerness to share their story because they knew it was important for so many reasons. But it was also challenging … we also met people who were not willing to engage or to do interviews with us because they lost a loved one, like 30 years ago. In many cases, the case is still unsolved. And there was this double pain, the loss of an individual, but also the context; in some cases people had double lives, they were not disclosing their sexual orientation to their family, right?

And memories can change decades later.

Yeah, it’s the challenge with interviewing people who will remember things from 30 years ago. Like if you ask anyone what they did last week or a month ago, often they won’t even remember accurately. Imagine 30 years. But I was still surprised by how much people remember and I think that’s also because it was so impactful. Like in their life, it had so much impact. So I think that’s why they had such vibrant memories of what happened.

I couldn’t help but notice the parallel between the attacks on gay men, who were blamed for the HIV/AIDS crisis, and the anti-Asian hate we’ve seen during the COVID pandemic. Was that something that struck you?

Oh, yes, that was so obvious. It was so obvious to me because I live in Vancouver and there’s a big Asian community and I was seeing the same thing in the early days of COVID. I mean, so little was known about the disease. There was this perception that it came from Asia and as such, people were targeting Asian people, trying to avoid Asian markets.

When [Rose] was attacked on the bus, a friend was with him and the first thing he told first responders was that he had AIDS so they would take precautions … but there were so many wrong ideas about protections for the diseases, like you avoid The Village, you don’t touch gay people, and all those those kinds of like misconceptions. It kind of fueled the homophobia that we noticed in Montreal and elsewhere as well; I don’t think that was specific to Montreal, but yeah, it was kind of impossible not to make the connection.