Much of the narrative around drug-related harm reduction is focused on initiatives that provide needle exchange and/or safe injection spaces, but local advocates are working to spread awareness about and help people who engage in other methods of substance use.

“What happens if you’re only focusing on syringe exchange, you’re missing people who don’t use syringes,” said Adrienne Standley, who does harm reduction work in Philadelphia and housing-related activism with the local chapter of ACT UP.

Standley and a group of people from ACT UP and other organizations co-created the harm reduction initiative SOL Collective in 2017, which works to “end the racist war on drugs, the overdose crisis and advocate for overdose prevention sites,” according to the collective’s Facebook page. The initiative formed around the time that City officials evicted people from “El Campamento,” a site where heroin users would inject drugs along the Conrail railroad tracks in Kensington. “The City evicted everybody and people got scattered, and the need for supplies grew pretty quickly,” Standley said.

According to the organization Addiction Center, a projected 20-30% of the LGBTQ population abuses substances, as opposed to 9% of the general population.

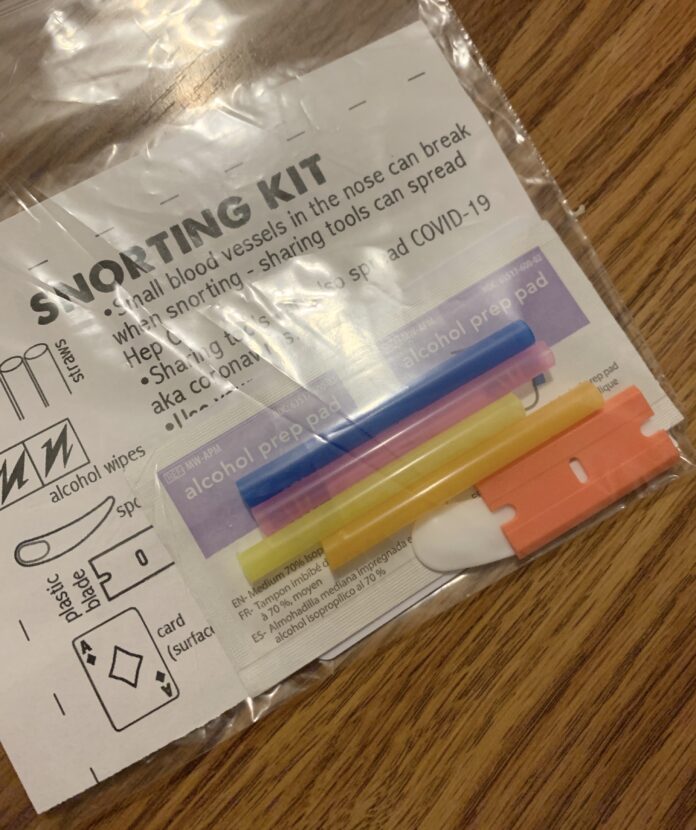

One aspect of Standley’s harm reduction work manifests in making kits that people can use to snort drugs more safely. They contain cut up plastic straws, a plastic razor to cut drugs, a card that serves as a clean surface, an antibacterial wipe and a plastic makeup spatula for snorting smaller amounts of drugs instead of doing lines. The clean, single-serving aspect of the safer snorting kit provides a barrier to spreading diseases like hepatitis C, which is a blood-borne disease, and COVID-19.

“We can avoid and prevent a lot of other harms, like using a straw instead of a dollar bill,” Standley said. “Dollar bills are not super clean.”

Although the team that runs SOL Collective started distributing safer snorting kits at one point in time, Standley started making her own when she began volunteering at the Free Market, a mutual aid market that takes place monthly at Malcolm X Park in West Philly. “They wanted to have narcan and harm reduction supplies,” she said.

As increased amounts of a potent tranquilizer called xylazine, also known as “tranq,” started showing up in dope (what used to be pure heroin but is now typically fentanyl or a melange of drugs), more and more people have started to snort it instead of inject it, Standley said.

“Tranquilizer when injected has led to some really bad abscesses,” she explained. “We’re not 100% sure why, but people have been getting so many more wounds, abscesses and injuries from injecting. So people have started switching to snorting sometimes to avoid that. Any method of ingestion that you can offer people a safer way to do it, allows you to talk to more people. Moving from injecting to snorting in this case is indeed harm reduction on its own.”

Another harm reductionist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, distributes Standley’s safer snorting kits, as well as narcan and fentanyl test strips, in queer nightlife spaces and parties in Philadelphia. The snorting kits have become increasingly popular, they said.

“I started giving them out to people and they were like, ‘wow, we f***ing love these,’” the anonymous source said. “I’ll go out myself and I’ll be at these bars, and somebody will be like, ‘I’m going to do coke in the bathroom.’ I’ll be in the bathroom and people pull out these snorters kits and it’ll be people I haven’t even met.”

In addition to distributing harm reduction materials, the harm reductionist works as a kind of medic for multiple event coordinators who run large indoor and outdoor events. They trained themself in first aid and have a background as a street medic.

“It’s rave culture — everybody’s dancing, it’s really hot and everyone’s on drugs or drinking,” they said. “It just kind of boggled me because it is so dangerous. I was like, ‘everybody here’s on ecstasy and there’s not one person just kind of checking on people.’ They had staff who were paying attention, but they didn’t have someone specifically to be eyes.”

Both Standley and the anonymous harm reductionist pointed out that harm reduction has deep roots in LGBTQ communities.

“It’s important because LGBTQ people are already at risk,” the harm reductionist said. “As a baseline, even if you’re not a party-goer or involved in nightlife. Finding yourself in nightlife culture is a really important part of the LGBTQ community. All of these ravers and people who throw events do it for each other. It’s just another thing to have each other’s back, to do harm reduction.”

The Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, which is based on responses from 34,000 LGBTQ youth 13-24 years old, reveals that 45% of LGBTQ youth seriously considered suicide in the past year, 14% attempted suicide in the same time period, and 73% said they experienced symptoms of anxiety.

Standley framed the importance of harm reduction as having a prominent place in the HIV/AIDS crisis “whether it was distributing condoms, or establishing syringe exchange programs, or all the other things people were doing to keep each other alive.”

“Keeping each other alive in community-based systems is always something that the community has done. I think that the distribution, dissemination and sharing of harm reduction supplies is part of that practice.”