In Spring 2022 I won another journalism award for my Covid coverage. With that humbling and welcome recognition, I thought my pandemic beat was drawing to a close. I’d written about every aspect of that killer virus, including the mass disabling event of Long Covid that has yet to be addressed by the Biden administration through either HHS or the CDC. PGN, which has long been on the cutting edge of coverage of medical issues impacting the LGBTQ community, allowed me to explore Long Covid in-depth in a three-part series for which I interviewed both experts and sufferers.

Then monkeypox happened.

Déjà vu. Times two.

Those of us who were activists during the AIDS pandemic went through an auto da fé: Our response to our friends, lovers and colleagues dying of the disease was forged in rage and heartbreak.

When I began reporting on HIV/AIDS for both the queer and mainstream press, little was known about the disease. It was the early years of discovery. And in that time, AIDS was a death sentence that took the lives of close friends, acquaintances and colleagues as well as the rich and famous.

Among the latter, men in their 30s, 40s and 50s who were prominent in a plethora of fields from politics to the arts were dying. Their obituaries listed pneumonia or cancer as the cause of death, but from the front lines of reporting on the epidemic, we learned to read the code: a Philadelphia City councilman; a well-known Philadelphia journalist; a news anchor, a restaurateur.

The door of the gay closet was still tightly closed, but the door to the AIDS closet was bolted.

These were the years of media referencing “innocent victims” of AIDS — the hemophiliacs and babies and those who got AIDS from transfusions, while villainous descriptions of gay men as deliberate and predatory purveyors of a fatal disease many saw as one they “chose,” were rampant.

When I was tasked with reporting on monkeypox back in May, I thought everything we’d learned from two pandemics decades apart (yet overseen by the same infectious disease specialist, Dr. Anthony Fauci) would facilitate a rapid and smart response. The Biden administration was a far cry from the previous one that had caused so much illness and death with its anti-science response to Covid-19.

Also, monkeypox had hit the U.S. before, in 2003, in an animal-related outbreak, localized to the Midwest. The government responded with speedy testing and vaccinations. It was over quickly and expeditiously, without community spread.

As the CDC told us in May, monkeypox isn’t Covid. It is “transmitted from one person to another by close contact with lesions, body fluids, respiratory droplets and contaminated materials such as bedding.”

It isn’t readily transmissible. It is rarely deadly. It’s been around for decades and we know almost everything about it, including how to test for it, how to treat it and how to contain it.

So why didn’t we contain it? Why did monkeypox explode? Or rather, why was it allowed to?

It seems simplistic to say it was because of who was getting the disease, but those of us who were AIDS activists recall the back-to-back administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush refusing to discuss AIDS. Reagan did not even mention the word AIDS until September 1985, when he responded to reporters’ questions. His first speech about the disease was delivered to the College of Physicians in Philadelphia in 1987 — six years into the pandemic.

Activists also remember what a seminal moment it was for a young President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton — both the same age as many of the dead — to walk the Capitol Mall examining the AIDS quilt.

Yet President Biden had spoken about monkeypox in May, soon after the outbreak began when there were still no reported cases in the U.S. So why did Biden wait to appoint a monkeypox team until this week, months after he first mentioned the outbreak? And where have HHS and the CDC been all this time? Other than assuring the cis-het public that they were ostensibly safe from getting the disease, that is?

Problematic too has been a lack of testing which in turn means a lack of accurate numbers. Together this paints a picture of less virulence — when in fact there is a fulminating pandemic.

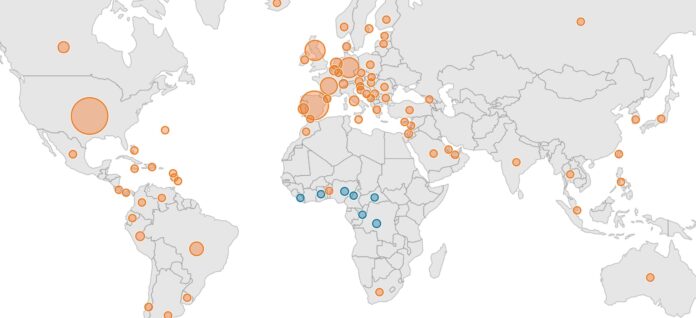

Add to that muted response of government and healthcare agencies a mainstream media slow to report on what is now a global health emergency. While I’m in month three of reporting on monkeypox every week, the newspapers and news outlets of record have been intermittent in their reportage as the U.S. climbed from one of the lowest global case loads to the highest in the world.

As The Atlantic’s Katherine Wu, who chronicled Covid for the magazine writes this month, “Although the U.S. might have once seemed like one of the nations best equipped to stop and prevent outbreaks, it is, in actuality, one of the best at squandering its potential instead.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) is not blameless here, either. The organization, which received harsh criticism over their handling of Covid-19, has dithered over declaring the outbreak a health emergency.

Yet the WHO knew there was potential for just this kind of outbreak because there had been a smaller and quickly contained outbreak among young gay men in Nigeria in 2017.

Again the answers to why this outbreak was allowed to spread circle back to those getting infected. People in historically marginalized communities like Black and Latinx people during Covid and gay and bisexual men during monkeypox have never fared well in the U.S. during times of disease outbreaks. Just as we saw limited testing and treatment for communities of color during the height of Covid, now we are seeing the same for people with monkeypox or at high risk of monkeypox.

Fold into that last part the fact that we are now in a heightened and truly dangerous period of anti-LGBTQ backlash, as I have been reporting for PGN and elsewhere. I just wrote about Ron DeSantis’s war on LGBTQ people. How long before he declares gay men suspect in the current monkeypox outbreak?

Yet as AIDS activist and writer Steven Thrasher wrote in June for Scientific American, “Blaming Gay Men for Monkeypox Will Harm Everyone.” Thrasher notes, “MPX has been popping up all over the world the last couple of months, with at least two strains in the U.S. alone, suggesting undetected global spread has been occurring for some time.”

So why did we ignore it while African nations — with so far fewer available tools for healthcare crises — consistently control and contain outbreaks in affected countries where the disease is endemic? Why did it take three months to even appoint a monkeypox team?

Stigma, lack of resources for sexual health clinics, failure to alert impacted communities, a long incubation period, Covid pandemic fatigue — all of these things have played a role in why gay and bisexual men were failed again by federal and state agencies tasked with protecting people, all people, from infectious diseases.

And now here we are.

Is it fair to say that no one considered the pain and suffering of gay and bisexual men with monkeypox to be worth addressing, since it is so rarely fatal? Perhaps it’s an unfair assessment. But it is, from all we have witnessed since May, also accurate. And there is absolutely nothing to suggest that approach will ameliorate any time soon.