This is part one of a three part series.

Masks came off a few weeks ago: a harbinger of Spring. On February 25, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officially made mask wearing a personal assessment of risk among the vaccinated and boosted. Yet a third of age-eligible Americans have yet to get a single shot and fewer than half have gotten a booster. The unvaccinated have resisted masks throughout the pandemic, a stance defined early in 2020 by Donald Trump.

Republican lawmakers have protested mask and vaccine mandates nationwide ever since President Biden made vaccines available and free to everyone and imposed a federal mask mandate and masking for companies with more than 100 employees. In the Pennsylvania Senate race, the top GOP candidate, Dr. Mehmet Oz, is running against masks. Oz has signaled “fire Fauci” — Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the Chief Medical Advisor to the President — as a top priority for him as a senator.

As the Omicron wave abated in March, vaccine and mask mandates ended in most public places. Predictably, COVID cases have been on the rise ever since: New York City Mayor Eric Adams, New Jersey governor Phil Murphy, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Attorney General Merrick Garland are among a myriad of high-profile politicians who have tested positive.

Clinically, there’s a correlation between masking and not getting COVID. Yet being vaccinated and boosted has proven to prevent serious illness and hospitalization. Even the Speaker, who turned 82 last month, has only mild symptoms.

As so-called COVID fatigue swept the nation, Americans have been eager to get back to pre-pandemic life. Warmer weather, baseball and concert season, and restaurants and bars reopening have all lured big crowds. Philadelphia’s shopping districts and restaurant sectors like Rittenhouse Square and Old City have been packed. The Gayborhood looks like there was never a pandemic. But within this celebratory exercising of masklessness and relaxed vaccine requirements, Philadelphia health commissioner Dr. Cheryl Bettigole made national headlines this week by reinstating the city’s mask mandate effective April 18, noting that “cases have increased by more than 50 percent in the previous 10 days.”

“This is our chance to get ahead of the pandemic,” Bettigole said in a news conference April 11. “Knowing that every previous wave of infections has been followed by a wave of hospitalizations, and then a wave of deaths, then it will be too late for many of our residents,” she said, explaining what would happen if the city waited until cases exploded again to impose the mandate.

Bettigole also cited Philadelphia’s history of racist response to health crises, a significant issue in a city that is 70 percent people of color and is also the poorest big city in the country.

“We’ve all seen here in Philadelphia, how much our history of redlining, history of disparities has impacted particularly our Black and brown communities in the city,” Bettigole said at the news conference. “And so it does make sense to be more careful in Philadelphia, than, you know, perhaps in an affluent suburb.”

Though the numbers are still low, Bettigole’s caution is not misplaced. While the latest B.A.2 Omicron surge isn’t causing a glut on healthcare services like the holiday Omicron wave did, and among the vaccinated symptoms appear minor, there’s another aspect of COVID that is rarely discussed: Long COVID.

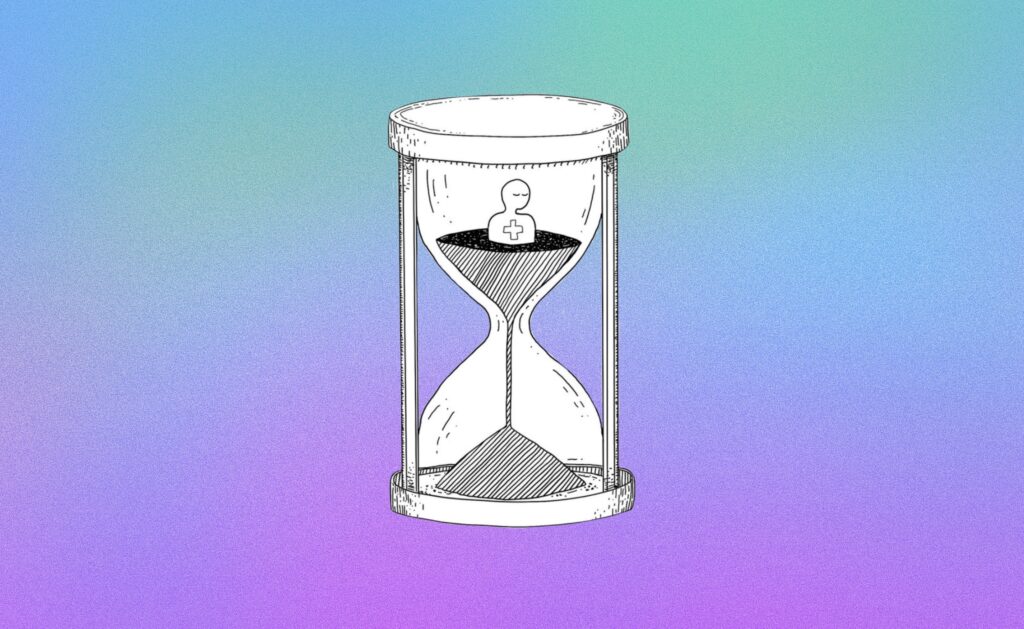

Long COVID has become the shadow pandemic with an alarmingly large swath of Americans reporting varying degrees of the disabling syndrome. On April 12 a Yahoo News/YouGov poll revealed 7 percent of American adults say they have experienced long COVID: 18 million people. Yet that’s an under-estimate according to other research. The New York Times reports “studies estimate that 10 to 30 percent of people infected with the coronavirus may develop” long COVID.

And April 12, two other researchers presented data saying “Long COVID affects 1 in 5 people following infection.”

They add that “Long COVID is much more than a collection of symptoms. Rather, it is a recognizable clinical syndrome (or set of syndromes) with well described underlying pathology.”

On April 12, Dr. Tom Frieden, former Obama CDC director and New York City health commissioner, tweeted in response to a new study,

“Estimates suggest 10-30% or more of people who get infected with Covid develop long-term symptoms. We’re continuing to learn more about long Covid, but there’s still a lot we don’t know about the condition and how to help people who are suffering.”

Equally disturbing is there is no clear indicator of who will develop this syndrome, although more women than men and more people under 50 than over 50 seem impacted, with people in their 20s, 30s and 40s bearing the brunt of this secondary epidemic. Long COVID is also not defined by how severe one’s case of COVID was nor, most alarmingly, if one was vaccinated or not.

Two years into the pandemic there have been one million American deaths and 82.1 million reported cases of COVID. Pennsylvania ranks sixth among cases, with 2.8 million, and deaths, with 44,442.

Pam Belluck, a Pulitzer Prize-winning health and science reporter for the New York Times detailed long COVID in a March 25 story, “Understanding Long Covid.”

“It involves a very varied constellation of symptoms, and it’s still quite mysterious,” said Belluck. “But a growing number of studies are shedding light on the range of symptoms and what they look like. And we’re getting some scientific clues about what seems to be happening in the body.”

What is known clinically about long COVID is limited, though studies are slowly coming to light that signal systemic inflammation as a major culprit. Bob Woodward first mentioned long COVID in one of his recorded interviews with Donald Trump in February 2020. Ross Douhat, longtime New York Times columnist and former senior editor of The Atlantic, revealed his own long COVID diagnosis in a column titled simply and despairingly, “How I Became a Sick Person.”

Unlike the virus that spawned it, long COVID is a chronic illness with a range of symptoms and there is no clear test for it. Like COVID, it’s systemic, impacting major organs, notably brain, heart, lungs and kidneys as well as the vascular system. Symptomology is varied among sufferers, as is the degree of illness. Some who develop the syndrome, which can appear weeks and even months after even a COVID case where the person was asymptomatic, are very sick, others more mildly so.

Several factors are now known to increase the chances of developing long COVID, but there could be more. And not everyone who has these risk factors gets long COVID and some who get it have none of these factors. Many people with long COVID have the following: high levels of viral RNA early in the period of initial infection; the presence of certain auto-antibodies; reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus which nearly everyone carries; Type 2 diabetes.

Several studies out this month, like that in Nature on April 5 indicate that many will never fully recover from whatever long COVID is.

Taryn Talley fears she is one of those people. In a phone interview with PGN, Talley, 44, detailed how long COVID took over her life and that of her wife, Erika. Charming, engaging, funny and empathic, it’s obvious that Talley’s life was incredibly full and focused prior to the case of COVID from which she never recovered. A design engineer for a utility company, Talley continued to try and work for a couple months after her allowable COVID sick leave ended, but when “I was lying on the floor of my office, vomiting into a trash can while sending an email,” she knew she had to go home and stay there until she was better.

That was in the summer of 2021. She’s still no better.

So sick that she was granted Social Security Disability (SSDI) on the first application, Talley suffers from the most common long COVID symptoms — and the most debilitating: migraine headaches, shortness of breath, crushing fatigue, brain fog, muscle weakness and pain. When her wife leaves for work she lines snacks up at the bottom of Talley’s bed in case she can’t get downstairs to get food for herself.

Most disturbing in Talley’s story is that she got sick in 2021 after being vaccinated and being “meticulous” about masking. In June, Talley and her mother took a trip to Texas to visit her grandfather, who was ill and wanted to see them. Talley had avoided travel throughout the pandemic, but said she thought her biggest risk would be the airport. Once in Texas, she would be staying with her elderly grandparents and going nowhere.

Talley didn’t count on her sister infecting them all with COVID, later revealing she hadn’t been masking. Talley’s sister had come by to visit with all of them. Talley hadn’t seen her family since the beginning of the pandemic; but her sister looked ill. She claimed to have a sinus infection, a life-long problem. Yet the morning Talley was scheduled to return home, she had begun to feel sick. Had she contracted her sister’s infection?

By the time Talley arrived home, she said she was devastatingly ill, describing her swift decline like the opening scenes of the pandemic thriller “Outbreak.”

Days later, her sister tested positive, as did Talley’s mother. Her grandfather was hospitalized with COVID and died of the virus. Yet that crushing loss was just the beginning of Talley’s story and the havoc long COVID would wreak on hers and her wife’s lives. And Talley is far from alone. Long COVID has hit America hard, and as with COVID itself, it has hit the LGBTQ community harder still.

Next week: How has long COVID hit the LGBTQ community harder than most, and what clinicians and researchers are doing to aid treatment and recovery.