James Baldwin, one of the most famous gay writers in America, said “If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.”

Quotes from Baldwin are endemic — particularly now as liberal white America struggles to wake up yet again to Black oppression and systemic racism. But for many, Baldwin’s explosive language about racism and his unflinching discourse on the politics of race are as unsettling in 2022 as they were in the 1950s and 1960s, when Baldwin’s writing was first published for a wide audience in the U.S. Reading and reciting Baldwin’s quotes is less harsh than reading his excoriating essays on why he had to flee the U.S. for Paris and an expatriate life at the age of 24 in 1948.

Born to a young single mother in Harlem, New York, Baldwin never knew who his birth father was. When Baldwin was a toddler, his mother, Emma, married a much older man, David Baldwin, a Baptist preacher who raised James as his own. Emma had eight children with David.

James Baldwin’s early life was defined in part by opposition to his stepfather, who hated white people and hated James’s intellectuality as well as James’s white friends. Biographers of Baldwin state that the relationship was fraught and that it came close to physical violence. And while James referenced David as “father” in his writing, there was no fealty in that relationship. James would find that later in relationships with his early male mentors, including Black painter Beauford Delaney and author Richard Wright, to whom he was compared by critics.

Baldwin’s early years were filled with poverty, discrimination and conflict. As the oldest child he left school early to help support the family, but it was grueling labor and no job lasted very long. He experienced racism at every level of his life and credits a white teacher and mentor, Bill Miller, as the reason he “never really managed to hate white people.”

It was while still a student that Baldwin would begin to thrive as a writer, first under Miller’s tutelage and later under that of Bill Porter, a Black teacher at Harlem’s Frederick Douglass Junior High School. At that school, Baldwin was first published in the newspaper. At the prestigious DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, Baldwin became immersed in the school’s magazine, The Magpie, on which he worked with fellow student, Richard Avedon.

Baldwin wrote constantly after that, and it was his driving ambition to be a writer, finally finding the connections he needed to do so in Greenwich Village. There he socialized with the white literati at left-leaning publications like The Nation and Partisan Review, and it was then that Baldwin began to be published regularly. In his essay, “The Preservation of Innocence,” Baldwin deconstructs violence against homosexuals in American society as an element of American society’s failure to mature on issues of sexuality and masculinity — what he termed “the protracted adolescence of America as a society.”

From his earliest junior high years, Baldwin was having relationships with other males, and in his twenties he had a succession of brief liaisons and a longer relationship with Eugene Worth. He had also had strong attractions to some men with whom he became friends, not lovers, like Marlon Brando. But it wasn’t until he moved to Paris and met Lucien Happersberger, a young painter with whom he fell deeply, and biographers say, obsessively, in love, that Baldwin was fully and comfortably out as a gay man. Happersberger was 17, Baldwin 25. The relationship lasted three years until Happersberger married, and it took some years for Baldwin to rekindle the friendship.

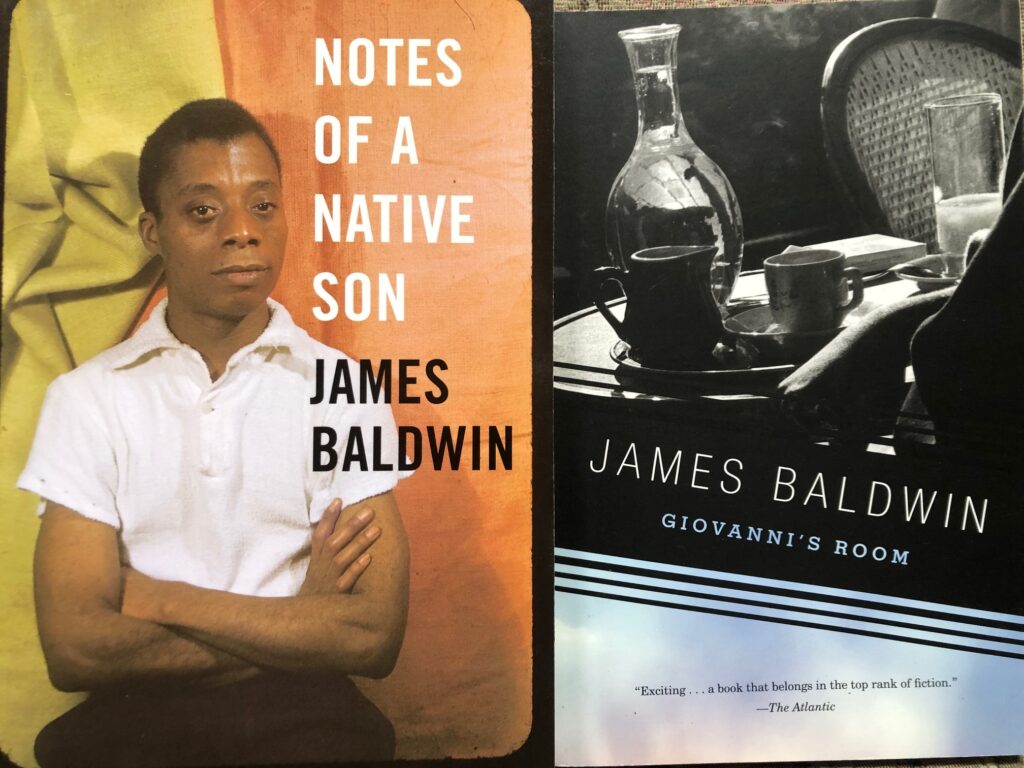

Baldwin wrote provocatively about men in his essays and novels and is widely credited with bringing a strong neo-realism to the depiction of gay and bisexual men in his fiction. But critics of his work at the time were uncomfortable with homosexuality, and that criticism devalues the relationships between and among the men in Baldwin’s novels, most notably “Go Tell It On the Mountain” (1953), “Giovanni’s Room” (1956), “Another Country” (1962), and “Just Above My Head” (1979). As Baldwin wrote: “Love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” And even more provocatively, as a man whose great loves were white men, “Nakedness has no color: this can come as news only to those who have never covered, or been covered by, another naked human being.”

Baldwin also explores what is now termed “toxic masculinity” and his deep delve into how men struggle to find their way to their own hearts and their own desire is a key element of that work.

While Baldwin expanded his literary oeuvre in Paris, his writing on race was becoming more and more influential in the U.S. as the nascent Black Civil Rights movement became more central to American politics. In “Notes of a Native Son” (1955), “Nobody Knows My Name” (1961), and “The Fire Next Time” (1963), Baldwin was writing about racism in the U.S. and Europe in ways that no one else was. Those essays are extraordinary for their incendiary exploration of what it means to be Black in a fundamentally racist America built on the blood and sweat and tears of slaves. As Baldwin would later write in “No Name on the Street,” “People who treat other people as less than human must not be surprised when the bread they have cast on the waters comes floating back to them, poisoned.”

Baldwin wrote extensively about how Black people in America were expected to assimilate into white society. “To become truly human and acceptable, [they] must first become like us. This assumption once accepted, the Negro in America can only acquiesce in the obliteration of his own personality.”

For Baldwin, the issue of racism toward Black Americans was very much the argument now being promulgated about Critical Race Theory: Baldwin saw American racism as emblematic of self-loathing and denial of the import of slavery, and this was layered onto Black people so that in order to be accepted by white people they had to be less Black. “One may say that the Negro in America does not really exist except in the darkness of [white] minds. […] Our dehumanization of the Negro then is indivisible from our dehumanization of ourselves.”

On May 16, 1969, Baldwin was a guest on “The Dick Cavett Show,” a cerebral late night talk show. The country had mourned two assassinations the previous year: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. Baldwin was on the show to talk about race in America and he touched on these themes of what white expectations were for Black people to be allowed full agency.

Baldwin is extraordinary and unflinching in his responses to Cavett, who asks well-intentioned questions about the “progress” Black Americans are achieving and the role of the Black Civil Rights movement.

“I don’t want to be given anything by you. I just want you to leave me alone so I can do it myself,” Baldwin says. “Perhaps I don’t think that this republic is the summit of human civilization. Perhaps I have another sense of life… Perhaps I don’t want what you think I want.”

Cavett asks Baldwin about Black radicalism — the Civil Rights leaders like Stokely Carmichael, who were less accommodating and who, as Cavett noted, “frighten us the most.” The “us” being white liberals like himself, trying hard to be hip to embracing Black people — at least intellectuals like Baldwin — as equals.

Baldwin is succinct as he says, “[When] any white man in the world says ‘Give me liberty, or give me death,’ the entire white world applauds. When a Black man says exactly the same thing, word for word, he is judged a criminal and treated like one.”

These comments about racism (there is much more in the segment) are peak Baldwin. His calm, forthright answers are discomfiting. He doesn’t care if he upsets white people; he was asked the questions and he answered them. As Baldwin wrote so succinctly, “I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do.”

Other videos of Baldwin talking about racism and about being a Black gay man resonate still; he says things that could have been said right now, or during the George Floyd summer of protest. A two-hour interview Baldwin gives with poet and activist Nikki Giovanni in London in 1971 is in large part about police violence and the assault on Black bodies. As Baldwin says, “…You always told me ‘It takes time…How much time do you want for your progress?” He also defines white liberals as “someone who thinks he knows more about your experience than you do.”

Another long talk with lesbian writer and activist Audre Lorde at Hampshire College is titled “Revolutionary Hope: A Conversation Between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde.” The talk, published in part in Essence Magazine, “discusses gendered difference between Black women and Black men against the larger stage of American racism.”

The work and words of James Baldwin are deeply and inextricably part of the American literary canon, even as his work still scares some white people as it addresses racism and some straight people as it addresses homosexuality and masculinity. Yet those works and words resonate and reverberate through our current reckoning on race and on queer ascendancy. As Baldwin wrote, “You have to decide who you are and force the world to deal with you, not with its idea of you.”