In the March 1977 issue of Philadelphia Gay News, Harry Langhorne wrote, in the boldly titled article “Temple Approves Gay Rights,” about how the university was set to be the first in the country to address marital status and sexual orientation in its Affirmative Action Plan. The plan, which was relayed in a letter from Temple President Marvin Wachman to Governor Milton Shapp, was approved in 1978.

One of the staff who was there in 1977 was Sandra A. Foehl, Temple’s current Director of Equal Opportunity Compliance. “One of the first meetings I ever came to at Temple, as a new employee, was on the issue of including sexual orientation and marital status in Temple’s Affirmative Action,” Foehl recalled.

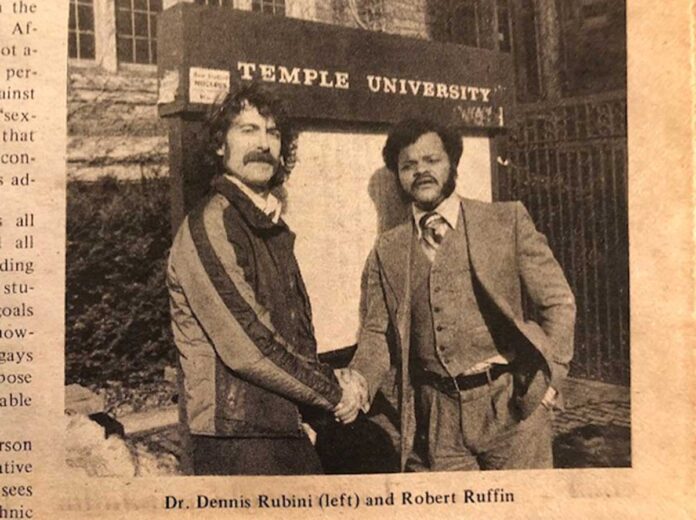

Foehl remembered the dedicated faculty at the time, especially Dr. Dennis Rubini, the professor and advocate who passed away in April 2012. Rubini wrote the original affirmative action proposal and, along with Gays at Temple, worked to push it through the university bureaucracy and get it signed by Wachman. Foehl acknowledged that faculty, then and now, oftentimes leads the demand for equal opportunities.

While Wachman stated in his letter to the Governor that he was “not aware of any instance where a person has been discriminated against because of marital status or sexual orientation,” he intended “that lack of discrimination shall continue to be the policy of this administration.”

Robert Ruffin, the head of the Affirmative Action committee at the time, told PGN that he hoped the decision reflected the university’s greater sensitivity to minority issues. “If you’re going to discriminate against gays, you’re going to discriminate against women, against blacks…this is a giant step in the right direction,” Ruffin said in 1977. Ruffin also said he thought Temple’s decision could lead to acceptance of gay people at other campuses.

The decision was not without skepticism, however. Then-chairperson of the President’s Affirmative Action Advisory Committee at Temple, Philip Schaeffer, drew a parallel between ethnic minorities and sexual orientations. Schaeffer skeptically argued that there has never been a demand for “a certain number of Germans or Irish.”

Another complicating factor, one which delayed Wachman signing off on the guidelines, were reservations stemming from the university’s legal counsel. Counsel told Wachman that because the university had a small number of students under 18, the open hiring of “admitted homosexuals” could potentially be seen as “violating the Commonwealth’s statute on corrupting the morals of a minor.” Wachman had also expressed concern that the term ‘sexual orientation’ was too vague. Both of the issues were ultimately allayed.

Seven years after the Action Plan passed, two Temple Law students successfully complained against another Temple University practice. Students Richard Brown and Loretta DeLoggio felt discriminated against as the university aided the military — which banned homosexual people from enlisting — to recruit on campus. The city Commission on Human Relations ruled in favor of the students.

More than two decades later, in 2000, the Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force published a yearlong study on LGBTQ+ experiences in the workforce. The study revealed that members of the community still felt discriminated against due to their sexual orientation. Larry Gross, the coauthor of the study and professor for communications at the University of Pennsylvania, told the Philadelphia Inquirer, “On the whole, the message is that there is a continuing, serious problem.”

Today, the faculty conversation concerning equal opportunities for all people within the LGBTQ+ community at Temple has lessened. The Temple University Faculty Senate Committee on LGBTQ Issues is on hiatus and has not been active since at least 2016, according to their website.

Dr. Tiffenia D. Archie, Associate Vice President and Chief Inclusion Officer, explained that there are several committees on hiatus and acknowledged that there is no malintent on the part of the institution. Dr. Archie added, “There’s a handful of faculty who is really interested in doing this work and the capacity is so minimum.”

The committee presented its last resolution on April 21, 2016. The resolution was a response to anti-LGBTQ measures from North Carolina and Mississippi and a sign of solidarity. It had been approved unanimously by the Temple University Senate.

Dr. Adrienne Shaw, a full-time faculty member at the Klein College of Media and Communications, pointed out that “LGBTQ+ and marginalized faculty are often asked to do a lot of service and unofficial advising/mentoring generally, and thus might be why it is hard to find faculty to serve on the committee.”

Nu’Rodney Prad, Director of Student Engagement for Temple’s Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity, Advocacy, and Leadership said that disclosing sexual orientation may be more difficult for staff and faculty than it is for students.

Prad said “This ‘coming out culture’ in itself is even being challenged. People are just being who they are and not necessarily seeking out those opportunities but being unapologetic for it.” Foehl added that faculty and students had a great sense of empowerment, yet staff had a greater sense of vulnerability to speak out.

Dr. Archie, when comparing the 1978 Action Plan to today’s practice at Temple University said, “The policy is the policy. It’s there. It’s the context that changes around the policy.”

Foehl is interested in seeing what the future may bring. She said, “There’s always a new avenue that our efforts can move along, it’s evident in the file. I am wondering what still might be coming along that will need a clear eye and some thoughtful examination.”

The President’s office, as well as the Temple Association of University Professionals, did not respond for comment.