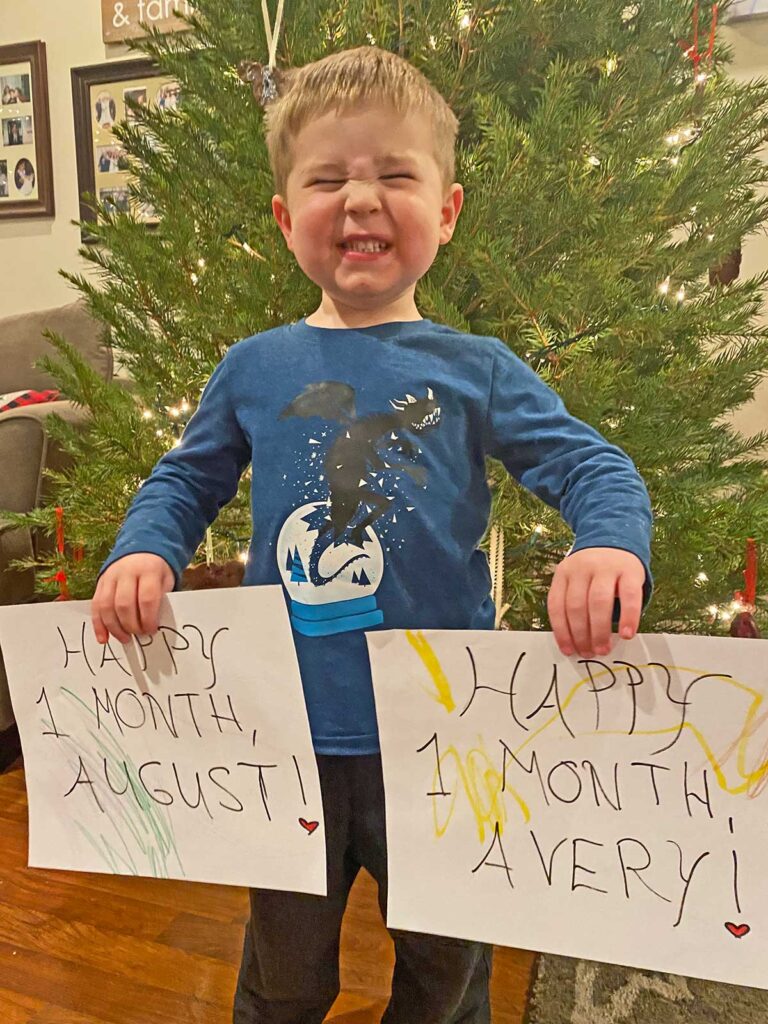

I gave birth to our twins, August Joseph and Avery Faith, on Nov. 11, at 9:18 p.m. and 9:20 p.m., respectively, with August clocking in at 2 pounds, 15 ounces and his sister weighing just 1 pound, 2 ounces. They arrived about 2.5 months early, after I was hospitalized with cord flow issues and pre-eclampsia, with my skyrocketing blood pressure the factor that eventually prompted an emergency C-section. With a high-risk, twin pregnancy, we knew that a stay at the neonatal intensive care unit was likely — but we really had no idea what it would look like, both for the babies and for us.

It was a whirlwind from the first minute. As soon as August was born, we cried in relief as we heard his wails, and the doctors brought him around to our side of the curtain so we could see him for about two seconds before he was whisked away to the waiting NICU team. When it was Avery’s turn, we didn’t hear any crying, and our panic was dialed up when the doctors got to work before we could even see her. Ashlee got to hold and take a quick picture of August while they were putting me back together but there was no cord-cutting, cuddles or any of the usual memory-making that accompanies a baby’s entrance into the world.

After my time in the recovery unit, the nurses wheeled my bed down to the NICU, where we got to see Avery for the first time and reach into both babies’ isolettes for a first touch, through a maze of wires, tubes and blinking lights. The ensuing month has itself been a maze, as we navigate a cascade of new medical lingo, routines we could have never prepared for, bonding with our babies through plexiglass, healing from surgery and, perhaps the biggest unexpected and complex aspect of all, caring for two babies in two separate NICUs in two separate states.

The routine

After about a week of August and Avery being in the Abington-Jefferson NICU, we were starting to feel like we could get a handle on the new routine. We knew where to park, the many hallways to turn down that would take us to the NICU and the tedious checking-in process: filling out a COVID screener, disinfecting our phones in a microwave box and scrubbing in, which involves soap and water up to the elbow for 20 seconds, followed by three rounds of antibacterial soap.

After being buzzed in, we would head straight to the end of the NICU to the twins’ “pod,” with two other babies, head-nodding to the same nameless parents we would see each day along the way. Then, we’d awkwardly linger outside their isolettes until whichever nurse was assigned to them recognized us, took my freezer bag of milk and updated us on their conditions: how many “Bradys” (a common preemie problem where they stop breathing momentarily and their heart rate drops) they’ve had, what their feed level is at, what percentage oxygen they’re getting. Often, we would be there when the physician team would round and would get the full run-down, complete with every blood work result and plans for upcoming imaging or other testing. Any visit would be planned around my pumping schedule, which has to happen every two hours and which itself is a complex routine of hooking up the machine, sorting and assembling all the parts, trying to keep my eyes open for 20 minutes and then cleaning the supplies, measuring the milk and storing and logging it in the hospital app. But the highlight of any visit was, of course, getting to hold the babies.

I say all of this in past tense because this routine was upended when the twins were just a week old: We got a late-night call that Avery had an intestinal perforation and had to be taken via ambulance to Nemours Children’s Hospital in Delaware, where she’s been since—through two intestinal surgeries, the placement of a brain shunt and more medical ups and downs than most adults, let alone a one-month-old, has or should have to face. The babies are now in their second month in both NICUs and, while we initially tried to visit both of them every single day, we knew we’d reach burnout level too quickly. We knocked it down to seeing each of them every other day, although when coupled with an hour-plus commute between the hospitals, a 3-year-old, two work schedules and Ashlee’s senior year of nursing school, any semblance of a normal routine is out the window.

An unnatural environment

Normalcy is hard to come by in the NICU, as just about everything you know or anticipate about having a baby is entirely backwards. It starts, of course, with the fact that after you give birth, you just leave the hospital and go back to your home and life that look the same as they did before — but they are anything but.

When Jackson was born, we had no idea what we were doing but we knew that he was entirely our responsibility — sleeping, diapering, feeding, bonding; we had to just figure it out. In the NICU, as the babies’ nurses are the ones with them in 12-hour increments, and we visit in blocks of a few hours, the nurses take the lead and parents may often feel like bystanders; as our parking pass and badges say, we’re “visitors.”

Apart from rattling off the babies’ medical stats as soon as we arrive, the nurses often share what their temperament has been like (we haven’t yet met a nurse who hasn’t called Avery feisty, while August gets rave reviews for his good behavior), which is an odd feeling to hear a stranger know how your baby acts better than you do. Every few hours they do what’s called “cares” — diaper change, adding milk to their feeding tube, taking their temperature — and ask us to join in, which we were initially terrified to do, as changing the diaper of a baby who’s barely the size of your hand and covered in wires and tubes is beyond daunting. It’s an uncomfortable juxtaposition to be afraid to care for your own baby and to be coached through it by someone you barely know.

That feeling is magnified whenever we hold the babies. We were apprehensive to even ask to hold Avery the first time when she was almost a week old, as she was still intubated and hardly more than a pound, but the nurses have been incredibly gracious and patient, walking us through the many steps of getting the little ones out of their incubators and into our shirts for skin-to-skin or what’s called kangaroo care. It’s a dizzying dance (sometimes literally) that involves the nurses hooking and rehooking, adjusting and readjusting, alarms going off — but it’s one of the few ways NICU parents have to bond with their babies. Despite wires being clipped to shirts and nurses repositioning their heads every few minutes if their vitals are off, that hour of closeness is like a salve for parents so deprived of that normal exchange of closeness with their babies.

Yet the environment in which you enjoy that growing bond is again out of the ordinary. Initially, I felt so awkward doing the usual cooing and shushing and telling the babies how beautiful their eyes are whenever they open them, as I always felt like I had an audience of nurses, doctors and even other parents. While I’ve gradually realized no one is probably listening to nor cares how I talk to my babies, it’s still an experience that can definitely make you self-conscious.

The tiny milestones we’re getting to witness are also happening amid the backdrop of a busy intensive care unit. Earlier this month, I arrived to visit August and saw shades pulled around the isolette next to him and heard sobbing; the nurse whispered to me that the baby next to him, who had arrived 10 days after he did, had just passed away. I felt like an intruder on the parents’ grief as I unwillingly listened to the doctors explaining the autopsy procedure and a priest delivering last rites; all the while, I was holding August’s hand through the incubator and witnessed his smile for only the second time, a moment that in other circumstances would have been a cause for celebration but, in this often-awful environment, seemed to clash with reality.

That all of this is happening at Christmastime also presents an unsettling dichotomy. Both hospitals are done up in their holiday finest with “Jingle Bells” and other tunes piping through the hallways but the jolly setting doesn’t mesh well with the machine beeps and crying babies.

And then there’s the complicating factor: COVID. Because of the pandemic, only parents are allowed into the NICU, which makes the experience even weirder, as family and friends only get to know your newborns through photos (although thankfully, Avery’s hospital allowed us to add two more family caregivers to our list once she was there for two weeks, so the grandmothers have gotten to meet her). However, earlier this month, both babies were without visitors for a week because of several COVID exposures we had; while we’re triple vaccinated and had no symptoms, we couldn’t risk a visit until we waited the incubation period and got our negative tests — and Ashlee had to spend that time at a hotel so as to not risk exposing me and Jackson from a separate encounter. Even though a week doesn’t sound like a long time, it was one-quarter of the babies’ lives at that point that we missed: August’s first bath and the first time he got to wear clothes, and we came very close to not being able to be there for Avery through her brain surgery. It’s an experience that has now filled me with blind rage any time I see people claiming the “freedom” argument in social media debates about vaccines and masks; I would hazard a guess that such individuals have never walked through a NICU in a pandemic and seen the rows upon rows of infants whose tiny lungs are working as hard as they can to keep them alive.

One day at a time

When I was initially discharged from the hospital, we tried to turn to our calendar to stay organized with visits, my doctor’s appointments, Jackson’s schedule — yet the newness of the entire NICU experience and all of the worry, fear and confusion that it brings make any kind of coherent thinking nearly impossible. Every time one of the babies, particularly Avery, has had a setback, it’s sent us into a spiral of meetings and calls with the doctors, googling diagnoses and prognoses, and being racked by anxiety about all the what-ifs and the hope for long-term health — which barely leaves any room to think ahead, let alone plan what Jackson will have for dinner that night.

We saw pretty fast that we’re not alone in this phenomenon. There’s a local nonprofit called Today Is A Good Day that supports NICU families and whose motto is “One day at a time” — as the sheer feeling of overwhelm all NICU parents experience makes it hard to look beyond those 24 hours. We’re taking this slogan to heart and have started planning out our lives one day at a time through a note on my phone — who’s visiting which hospital, who’s picking Jackson up, food shopping, our work schedules, Ashlee’s classes, the babies’ medical procedures. And when it comes to their health, we’re doing our best to step back from the big picture and celebrate the small wins, focusing on those days that are good days — when Avery was extubated (for the third time) or when August hit four pounds.

However, even taking it just one day at a time doesn’t stop the emotions: The fear is constant. At the hospital, there’s little else to do when we’re holding the babies than stare at the monitors, and whenever we see the heart rate drop quickly, ours skyrocket until a nurse comes in. And when we’re home, if a phone rings, we drop whatever we’re doing and run to it, terrified it could be another emergency call.

On top of fear, being a NICU parent means constant guilt. Any time I leave either hospital, I worry I wasn’t there long enough or that the baby will struggle to bond with me since he or she spends more time with the nurse. We decided to give ourselves a break on Thanksgiving and see August in the morning and then spend the rest of the day with Jackson, making me feel awful that Avery didn’t have any visitors. We changed Jackson’s part-time preschool schedule to full-time and every morning when he whines “Am I going to school again?,” it breaks my heart. When I’m holding August, I’m often on my phone checking the video feed from Avery’s hospital of her isolette or when I’m holding Avery, I’m scrolling through the photos Jackson’s school sent over that day. Ashlee and I know it’s impossible to be in three places at once, but that doesn’t stem the worry that we’re not living up to what our kids need — because right now their needs are so new and so foreign to us.

But, like many NICU parents, we’re trying to just focus on what we do know we can provide: an endless amount of love and a willingness to use this experience for good. The NICU brings with it a lot of hard times, but I can already see the beginnings of NICU lessons that are going to impact how we parent these three: not sweating the small stuff, having patience with yourself and others, the healing power of generosity. We may rack up a lot of therapy bills one day because of this experience but I’m hoping it will also make us better parents — and ultimately shape the lives of our kids and those whom their lives touch for the better.