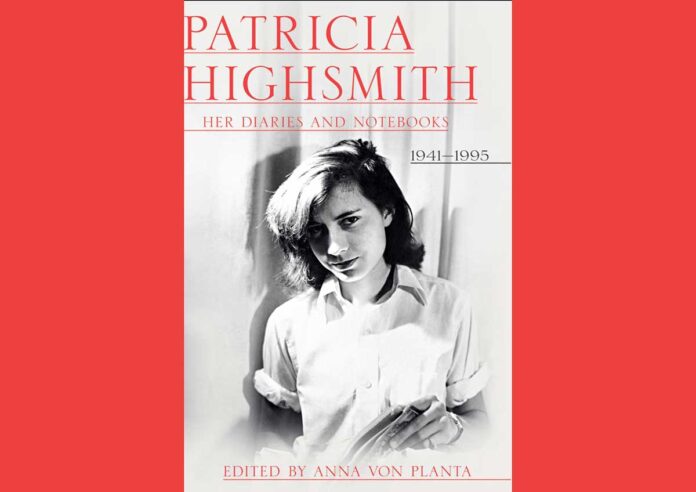

Patricia Highsmith would have been 100 years old this year. Marking her centenary year is the publication of “Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks, 1941-1995,” an intimately detailed exploration of a half century of the life of the iconic lesbian writer.

Joan Schenkar, author of “The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith,” wrote the afterword for the collection. Schenkar said, “Highsmith’s astonishing candor in the witness stand of her personal notebooks, and heartbreaking self-exposures in the jury box of her diaries, are like nothing else in American confessional literature.”

That is a most accurate assessment. At 999 pages, this is absolutely Highsmith’s masterwork. She delves deeply into her own psyche on page after page, and within that she explores a panoply of topics, from her own voracious sexuality to her writing to, later in life, a complicated and often unpleasant personal politik, which was socialist Democrat yet included venomous anti-Semitism and blatant racism.

Highsmith wrote 22 novels and numerous short stories throughout her career. Graham Greene said of her taut, tantalizing thrillers that she was “the poet of apprehension rather than fear.”

Michael Dirda of the New York Review of Books said of her bisexual antihero-cum-sociopath, Tom Ripley, “‘The Talented Mr. Ripley’ and its companions should at least rank among the most perversely entertaining novels of our time.”

Highsmith’s work has been adapted for films over a dozen times. Her most famous work is her first novel, “Strangers on a Train.” That book was adapted for both the theater and the movies. The 1951 Alfred Hitchcock film, with a screenplay by Raymond Chandler, is considered a noir classic and ranks among the best of Hitchcock’s films. The Ripley books have also been adapted.

Writing under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, Highsmith published “The Price of Salt,” in 1952. The lesbian pulp classic was republished in 1990 as “Carol,” this time under Highsmith’s own name. As the diaries reveal, this was a book very much written about her own experiences as a young lesbian in New York City drawn irrevocably to older women.

The 2015 film adaptation of “Carol,” with an Oscar-nominated screenplay by Phyllis Nagy, and starring Oscar-winner Cate Blanchett, garnered numerous awards and has been ranked by the British Film Institute as the best LGBT film of all time.

Throughout her diaries, Highsmith writes about writing. She teases out the meaning of Ripley as a character and how fascinated she is by getting readers to root for the monster — the man who is actually and willfully evil. On October 1, 1954 she writes, “What I predicted I would once do, I am doing already in this very book (Tom Ripley), that is, showing the unequivocal triumph of evil over good, and rejoicing in it. I shall make my readers rejoice in it, too. Thus the subconscious always precedes the conscious, or reality, as in dreams.”

But while many will read these Highsmith diaries to get a sense of her motivations as a writer, what is most compelling for the queer reader is Highsmith’s open and uncensored detailing of her sexual escapades and her volatile relationships with women. Highsmith was very much in love with love — and sex — as a young woman. At 20, she writes, on August 7, 1941, “Sex, to me, should be a religion. I have no other. I feel no other urge, to devotion, to something, and we all need a devotion to something besides ourselves, besides even our noblest ambitions. I could be content without fulfillment. Perhaps I should be better off in such an arrangement.”

She writes on September 24, 1943, “Sexual love is the only emotion which has ever really touched me. Hatred, jealousy, even abstract devotion, never — except devotion to myself. But love touched me willy-nilly.”

The early decades of these entries (the 1940s through the early 70s) are dominated by Highsmith’s love affairs and sexual affairs with other women. It is these entries that are perhaps the most revelatory as they are so broadly removed from how women wrote about love and sex. Lesbian writing of that period had been especially hidden from view. But Highsmith writes about it with excitement and joy.

Yet Highsmith worked to maintain her privacy. She wrote her entries in a multiplicity of languages, all painstakingly translated and decoded by her long-time editor, Anna von Planta, who edited this massive book.

The entries range from 1941, when Highsmith was a student at Barnard College and right before the U.S entered World War II, to 1995, the year Highsmith died in Switzerland of lung cancer and aplastic anemia at 74.

As von Planta details in her introduction, the book is culled from 8,000 pages of handwritten entries in 56 notebooks and diaries by Highsmith. These were written in English, German, French, Spanish and Italian to keep them private during the decades that Highsmith was so openly out as a lesbian, while having to maintain a professional decorum for the homophobic publishing industry.

These conflicts weighed on Highsmith, who suffered from bouts of depression throughout her life and frequently questioned her own stability as well as what her life was about and what her relationships have meant.

Highsmith talks episodically about being a lesbian and how that has impacted her life. On October 16, 1954, she wrote, “On the grudgingness of my chosen partners, and my consequent low estimation of myself, I believe this self-depreciation partly due to my evil thoughts, of murder of my stepfather, for example, when I was eight or less. Also the realised taboo of homosexuality, my realisation, even at six, and at eight, that I dared not speak my love, and of course this persisted with its adult ramifications of social life, guilt. Unfortunate that this is so buried, for consciously I am not in the least ashamed of homosexuality, and if I were normal, and equally imaginative, I should probably consider it very interesting to be homosexual, and wish I’d had the experience. Attitude toward money (and in the 20s, on my own) and recent one of overspending and carelessness. Also toward food during these years. Saving part of anything, living like a rat. Self-depreciation. Lack of food intake in adolescence, to get attention of parents, also to punish myself, for sex reasons, etc.”

That need to punish herself, those bouts of what we would now term self-loathing, start to define her relationships as she gets older. Her relationships, like her long-term affair with Marijane Meaker, who wrote lesbian pulp fiction under the pseudonyms Vin Packer and Ann Aldrich and young adult fiction as M.E. Kerr, falter and dissolve.

After writing for 20 years about her love affairs, Highsmith begins, at middle age, to question her priorities.

On May 29, 1961, at 40, she wrote, “What is life all about? It is the futility and the hopelessness that obsesses and overwhelms the philosophers. If I am lucky, when the darkness closes in, and the senses drop out one by one, there will be a couple of friends standing by, who knew me. This is what life is all about. It’s no different if one has children and passes on the race or the family. Life is about nothing but hopes of contacts. Friendships are the most durable, and really the most profound contacts, though people are often deceived into thinking that the sexual is the most profound. It is pleasurable and it appears to rearrange the emotional structure, but it does not.”

There is so much more to be said about this compendium of Highsmith’s most intimate work. It is immensely readable, always fascinating and well worth your time.

“Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks, 1941-1995” is available at booksellers nationwide.