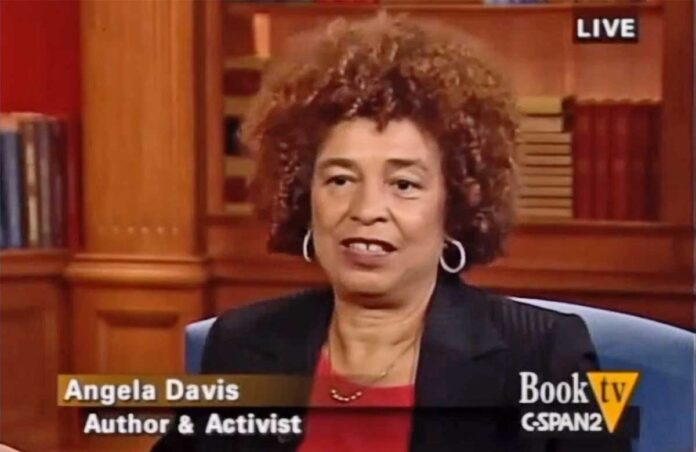

“You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.” So said Angela Davis, 78, America’s most famous living revolutionary. She was born in Birmingham, Alabama, one of the most incendiary of the racist Jim Crow southern cities, in a neighborhood called “Dynamite Hill,” due to attacks on Black people by their white neighbors. Davis would rise to become an international beacon of anti-racist and feminist radicalism over decades, expanding her vision to include LGBTQ civil rights, Palestinian rights and her life’s work against America’s carceral system.

A radical political activist and theorist, Davis gained fame in the 1960s and 1970s as a leader in the Black Civil Rights, Black Power and Black and feminist liberation movements. Pivoting off the Serenity prayer, Davis’s most famous quote is the one that threads through all her activism: “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.”

Davis continues to do that work now, 60 years after enrolling at Brandeis University as one of only three Black students. After graduating from Brandeis, Davis studied with Frankfurt school philosopher Herbert Marcuse in Berlin. In a 2007 television interview, Davis said, “Herbert Marcuse taught me that it was possible to be an academic, an activist, a scholar and a revolutionary.”

Davis was and is all those things. In 1969, while a professor in the philosophy department at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and already a world-renowned activist, Davis was fired for being a Communist and for her “inflammatory language.” Davis was also a member of the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panthers at that time and identified as a radical feminist. Her firing was both urged and lauded by then Gov. Ronald Reagan, despite national support for her. UCLA’s Board of Regents was censured by the American Association of University Professors for firing Davis.

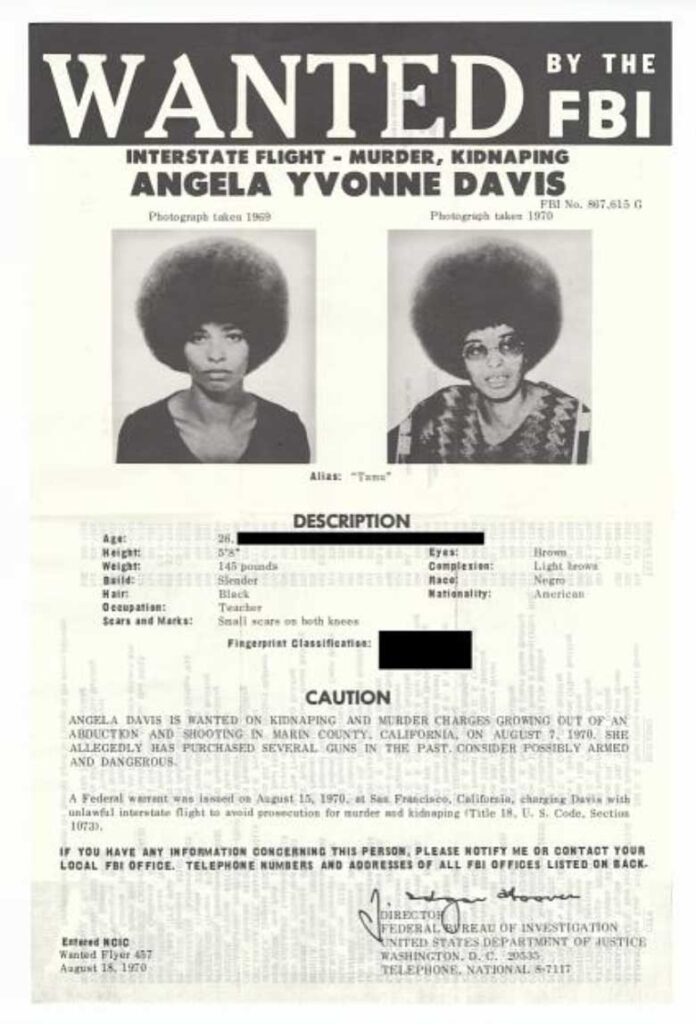

The following year, Davis was listed among the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted, the first Black woman to be on the FBI’s fugitives list, personally chosen by J. Edgar Hoover. The listing and subsequent manhunt came after guns Davis had purchased were used in an August 1970 shooting at the Marin County courthouse in California related to the Soledad Brothers, whom she supported as political prisoners.

The manhunt for Davis was massive, but it took several months to track her down, eventually resulting in her arrest in New York City. When Davis was apprehended, President Richard M. Nixon congratulated the FBI on its “capture of the dangerous terrorist Angela Davis.”

But Davis was no terrorist and was acquitted of all charges after a 16-month prison stay without trial. An all-white jury deliberated for only 13 hours before finding her not guilty on June 4, 1972.

Davis’s arrest and imprisonment were focal points for other activists and heightened her political profile and activism. Black writers formed a committee called the Black People in Defense of Angela Davis which grew to hundreds of chapters in nearly 70 countries. John Lennon and Yoko Ono wrote a song, “Angela,” in support.

Davis’s incarceration — much of which was in solitary confinement — was a pivot for her own work on prison abolition, a central focus of her political activism over decades. But Davis’s work has also been informed by her feminism and her time in Europe studying in Germany and working with activists there. She also visited Eastern Bloc countries in the 1970s and studied in East Germany.

Davis came out formally as a lesbian in 1997 in an interview with Out magazine. Her life partner is fellow professor and scholar Gina Dent, with whom she has collaborated on several projects.

A lifelong Communist, in 1980 and 1984 Davis was the Communist Party’s candidate for vice president. She subsequently split from the Communist Party and in recent years supported Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden for president, noting that it was essential to vote against the Republican Party leadership and oust them from the White House.

On prisons, Davis’s writing is succinct as she links a series of social issues to America’s carceral system which fosters racism and in which LGBTQ people are disproportionately imprisoned. She argues, “Prisons do not disappear social problems, they disappear human beings. Homelessness, unemployment, drug addiction, mental illness, and illiteracy are only a few of the problems that disappear from public view when the human beings contending with them are relegated to cages.”

In a 2020 interview, New York Times reporter Nelson George wrote of Davis, “Before the world knew what intersectionality was, the scholar, writer and activist was living it, arguing not just for Black liberation, but for the rights of women and queer and transgender people as well.”

George also detailed Davis’s focus on prisons, prisoners and abolition. A co-founder of Critical Resistance, an organization dedicated to abolishing the prison system, Davis has also written extensively about abolition and prisoners rights. In her 2003 book “Are Prisons Obsolete?” Davis argues for “decarceration” and “for the transformation of the society as a whole.”

In that book Davis writes, “The most difficult and urgent challenge today is that of creatively exploring new terrains of justice, where the prison no longer serves as our major anchor.”

It is a revolutionary concept.

Davis has adapted her argument to describe “the abolitionist imagination” and “the mentality needed to see beyond how law enforcement works versus how it is currently.”

Collaborating with her partner Gina Dent, and Erica R. Meiners and Beth E. Ritchie, Davis wrote “Abolition. Feminism. Now.” which comes out in January 2022 from Haymarket Books.

In her interview with George, Davis talked about the protests in the summer of 2020 and made another causal link between police violence — which also spurred gay and trans people at Stonewall: “The abolitionist imagination delinks us from that which is. It allows us to imagine other ways of addressing issues of safety and security. Most of us have assumed in the past that when it comes to public safety, the police are the ones who are in charge. When it comes to issues of harm in the community, prisons are the answer. But what if we imagined different modes of addressing harm, different modes of addressing security and safety?”

Over the decades since her formal coming out, Davis has worked with and supported LGBTQ activists and activism. She frequently references the perils of “hetero-patriarchy” and lauds the work of the queer and lesbian women who founded Black Lives Matter in 2013.

In a 2004 in an interview on C-SPAN, Davis spoke about the Black Civil Rights movement and parallels to the LGBTQ civil rights movement. She said that the Black movement “created a terrain” for both second wave feminism and LGBTQ rights movements.

Archivist Lisbet Tellefsen, a longtime friend of Davis’s, asked her if she preferred to be labeled as queer or lesbian while working on a project highlighting the activist’s life: “Angela Davis: OUTspoken at the GLBT Historical Society Museum.” Tellefsen said in an interview with KQED, “She’s like, ‘I don’t mind it.’ I’d prefer anti-racist, anti-capitalist.”

While Davis demurs from speaking directly about her own experience as a lesbian, she is often in concert with Dent in interviews and lectures. And other Black lesbian and queer women are determined that Davis be recognized as gay, as several pieces during Pride 2020 proclaimed. One of these had the in-your-face title: “Angela Davis Is a Dyke and Don’t You Forget It,” and argues that there is an investment in de-gaying Davis for that hetero-patriarchy Davis herself calls out.

In 2019 Davis was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and in 2020, she was listed as the 1971 “Woman of the Year” in Time magazine’s “100 Women of the Year” edition, which covered the 100 years that began with women’s suffrage in 1920. Davis was also included in Time’s 100 Most Influential People of 2020.

In “Freedom Is a Constant Struggle,” Davis gives a template for activism and recording our own stories. She writes, “Our histories never unfold in isolation. We cannot truly tell what we consider to be our own histories without knowing the other stories. And often we discover that those other stories are actually our own stories.”