In July, 2021, members of the local iteration of AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) convened for a peaceful action outside of Mayor Kenney’s Old City home to demand stronger housing resources. Before they could even start, Philadelphia police officers on the scene became abrasive when one ACT UP member was allegedly standing on a private driveway. ACT UP organizers disputed police claims that an officer merely placed their hands on the individual’s back to escort them off the property, saying that the officer forcefully pushed the person. Violence broke out from there, culminating in the hospitalization of four ACT UP members, two of whom were arrested for assaulting a police officer.

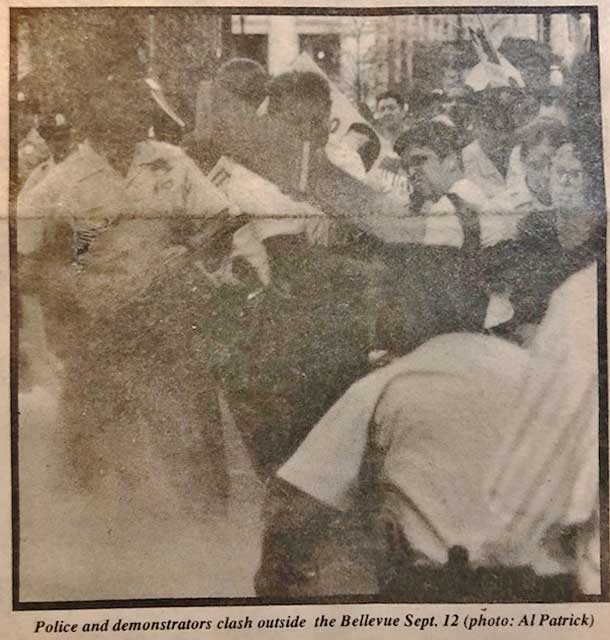

This is not the first time that Philadelphia police officers have violently intervened in an ACT UP protest. On Sept. 12, 1991, members of ACT UP and other activists, including the National Organization for Women and the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Savador, organized a protest against George Bush while he attended a fundraiser at the Bellevue Hotel for Republican senatorial candidate Richard Thornburgh.

At the time, PGN reported that police beat ACT UP organizers with night sticks and black jacks as protesters tried to stage a “die-in” in front of the Bellevue. Eight people were arrested on several charges, including disorderly conduct and rioting.

“As I recall, they just sort of came at us with batons and grabbing people, throwing people, hitting people, yelling at people, calling people faggots,” said former ACT UP Philly member JD Davids. “There was one person [living with AIDS], when he was knocked to the ground he started bleeding from the head and no one was allowed near him to assist him.”

Peg Conway, executive director of the Mayor’s Commission on Sexual Minorities in 1991, was one of the people who tried to help the injured man. PGN reported that when Conway approached a police officer telling them that she was an employee from the Mayor’s Office, the officer pushed her and knocked her to the ground more than once. When she attempted to ID the officer, he covered his badge and avoided identifying himself. Conway told PGN, “what sense is it to have a liaison from the Mayor’s Office if the liaison is treated like this?”

Police also knocked a TV cameraman to the ground, and at least one person who was arrested sustained a head injury bad enough to need four stitches.

At a press conference following the incident, Police Commissioner Willie Williams said that protesters throwing bottles at the police may have instigated the violence. However, protesters and eye-witnesses contradicted this claim.

“They have to pay for this,” ACT UP member Helen Kollenda told PGN. “We were protesting within our bounds as protected by the first amendment.”

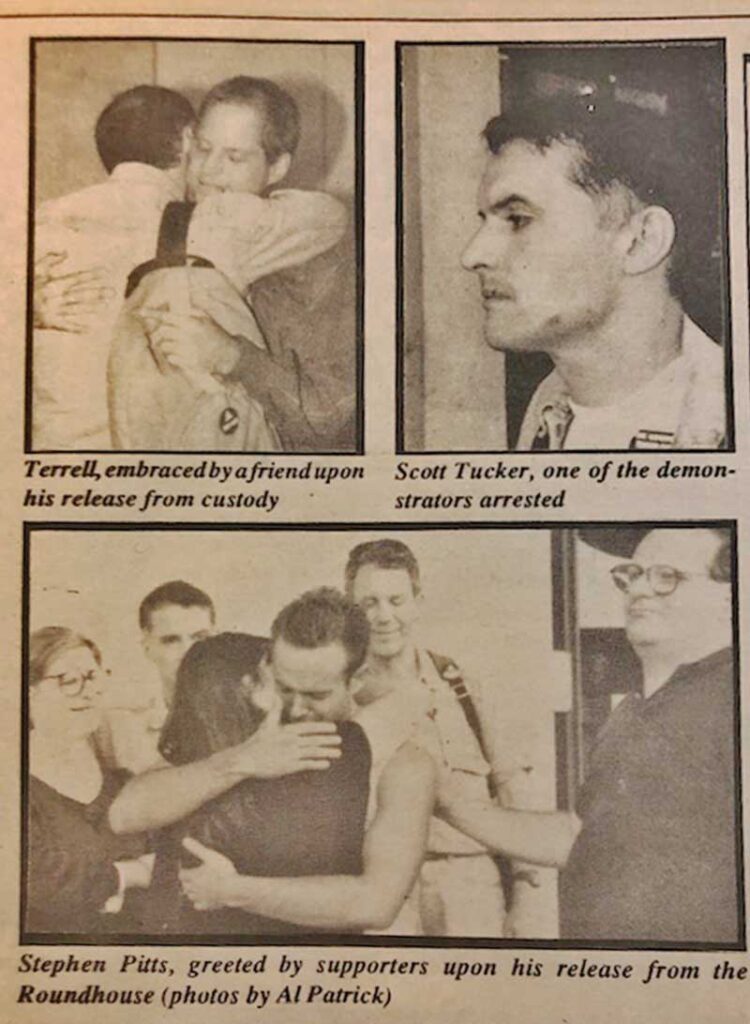

Police arrested ACT UP members Paul Arcure, Coleman Terrell and Stephen Pitts on several charges including aggravated assault, simple assault, reckless endangerment of another person, riot, failure to disperse and disorderly conduct. Terrell was further charged with escape and hindering apprehension. All three were later released on bail. Several other ACT UP organizers were arrested for disorderly conduct, but were issued citations and released.

Williams told PGN at the time that he would carry out an internal police investigation, and that “if we need to have more sensitivity training the department, it will come out in this investigation. We’ve had [sensitivity training] for 10 years.”

In a response to Williams, Scott Tucker, one of the arrested, said at the time: “What does sensitivity training mean? Does it mean that they beat us up but don’t call us faggots?”

Davids and his comrades were told that misinformation from the Secret Service fueled police bias toward ACT UP in addition to existing institutional prejudice. “The Secret Service was saying that ACT UP threw infected blood,” Davids said. “There was a lot of bias around not just queer people, not just people with AIDS, but also ACT UP in particular as a sort of militant force.”

Davids added that police specifically went after ACT UP members despite the presence of many other organizers in the crowd of about 7,500 people. “It was very clear that we were targeted, and we were targeted because we were queer and we were people with AIDS.”

Following the 1991 incident, ACT UP members and members of other social justice organizations sued the City of Philadelphia and individual police officers for unlawful conduct and violating their first amendment rights, and won. The suit included monetary compensation, an injunction against the police, barring them from intervening in ACT UP demonstrations for 10 years, a statement from the courts declaring the police behavior unconstitutional, and attorneys fees.

“That’s pretty funny because they already aren’t allowed to violate the civil rights of protesters, that they would have been in violation of an injunction if they had done so,” Davids said.

In less than two decades, this was the fifth suit brought against the City and the Philadelphia Police Department for infringing on protesters’ constitutional rights, PGN reported.

“What we hope to accomplish with this suit is that some elected official will say this is enough and something has to be done [about police brutality in this city],” Stefan Presser, one of the attorneys who represented ACT UP and the other plaintiffs, said at a 1991 press conference.

Davids emphasized the solidarity within ACT UP Philadelphia, that its members experienced the events of the 1991 protest together and were there for one another.

“We were there to support each other before, during and after, and that’s the importance of being in our movement groups that are rooted in love and caring for one another. Part of what we do is go through trauma together rather than alone. It was a bad experience but it was also a group experience.”