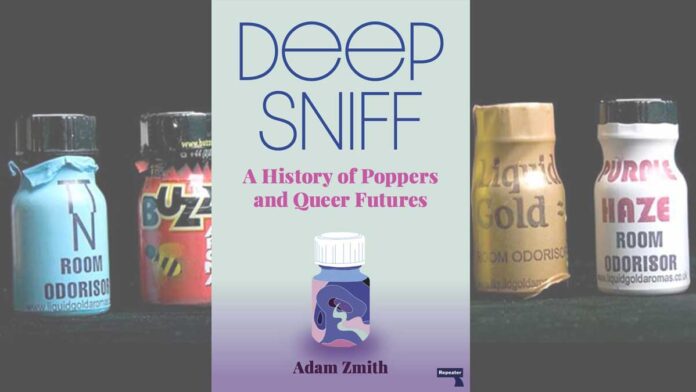

“Deep Sniff: A History of Poppers and Queer Futures” is a timely new book by queer British author Adam Zmith.

Poppers, those tiny bottles of amyl nitrite with lurid brand names like Jungle Juice and Premium Iron Horse, are in the news again.

This past June, the FDA issued an advisory urging people not to purchase or consume poppers. Meanwhile in Canada, liberal and conservative politicians are currently considering a review of the government’s policy on amyl nitrite products, which have basically been banned since 2013.

Zmith’s heady paean to poppers is unlikely to offer any guidance to sober-minded policymakers, but that’s not his aim. His intended audience is what he calls the QUILTBAG, “people who are queer, undecided, intersex, lesbian, transgender, bisexual, asexual and/or gay.”

Zmith’s goal is twofold. First, he’d like to liberate his peers from narrow and constricting labels like “gay” and “masculine.” “When we press beyond the limits of a category,” he says, “we find we have very promiscuous desires and erotic imaginations.”

Transcending those categories, Zmith believes, will enable us to imagine a truly emancipated future, or queer utopia. It’s not an actual place or a particular time but rather a state of mind. As he describes it, “Queer utopia is the feeling that your body is yours, it’s free and full of potential, and it’s not poisoned by anyone or their ideas.” Taking poppers seriously is one way he hopes to achieve that goal.

Zmith considers 1867 crucial. That’s when Thomas Lauder Brunton, a Scottish doctor, published a paper detailing his successful use of amyl nitrite to treat patients suffering from angina pectoris. It’s also the same year that the German jurist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, an early gay rights pioneer, publicly declared that it was perfectly fine for one man to love another.

What links them, according to Zmith, “is that the same year they both saw the potential of our bodies to be eased from suffering and to live fuller lives.”

It helps that Zmith isn’t a disinterested observer; in fact, he’s a poppers enthusiast. When he considers so-called “popperbator trainer videos” on Pornhub, for example, he doesn’t prudishly dismiss them as absurd or demeaning. On the contrary, he says, “These artists are building their own sexual utopias, filling them with the bodies, actions and music they like.”

Throughout “Deep Sniff,” Zmith’s approach is allusive, not argumentative. He’s especially alert to coincidences and often juxtaposes two seemingly disparate events or figures to illuminating effect.

Consider his discussion of Pacific Western Distributing Corporation. The company, which makes poppers brands that still exist, including Rush and Locker Room, was founded in 1976. “It was the same year that other durable US brands were founded: Microsoft, Apple, Starbucks,” Zmith notes.

It’s a clever riposte to people who dismiss poppers as trivial. Other parallels that Zmith notices are even more thought-provoking. Chapter three begins with an examination of masculinity in 1950s America.

Zmith considers fictional characters like Frank Wheeler in Richard Yates’s novel “Revolutionary Road” representative of the limited options available to men returning home from World War II: faithful husband, dutiful father, and conscientious employee.

By the 1970s, Zmith points out, the pages of gay male porn magazines are filled with images of musclebound, cigar-chomping men, often wearing blue-collar clothes or military uniforms. An advertisement like the one gay artist Rex drew for Bolt poppers, “The product specially manufactured for Heavy Duty,” is typical. It shows two hot studs with ample bulges at their crotch pumping gas for a bare-chested motorcyclist.

As Zmith explains, “These images, names and slogans drew on concepts that were associated with strength and the supposedly butch pursuits of fixing things or blowing them up.” In other words, they’d be instantly recognizable to Frank Wheeler.

By the end of the 1970s, public perception of poppers started shifting. What began as a life-affirming enhancement of sexual pleasure quickly became associated with certain death. In the early 1980s, when the first reports of gay men experiencing an outbreak of rare cancers emerged, doctors and scientists suspected a correlation between poppers and what became known as AIDS.

“The dream that gay sex was a valid way to live was turning into a nightmare,” Zmith says. “Suddenly, it was a way to die.” Scientists eventually established that HIV causes AIDS, not poppers, but negative associations with amyl nitrite linger.

Despite that, Zmith still sees enormous potential for this disreputable, hedonistic product. Its evanescent form — a liquid whose vapor is sniffed to provide an ephemeral feeling of euphoria and momentary loss of self — points to a fluidity that reaches far beyond heteronormativity.

Perhaps queer filmmaker Drew Gregory put it best: “I want to live in that moment I inhale chemicals out of a bottle. I want to live in those forty-five seconds when it all feels possible.”