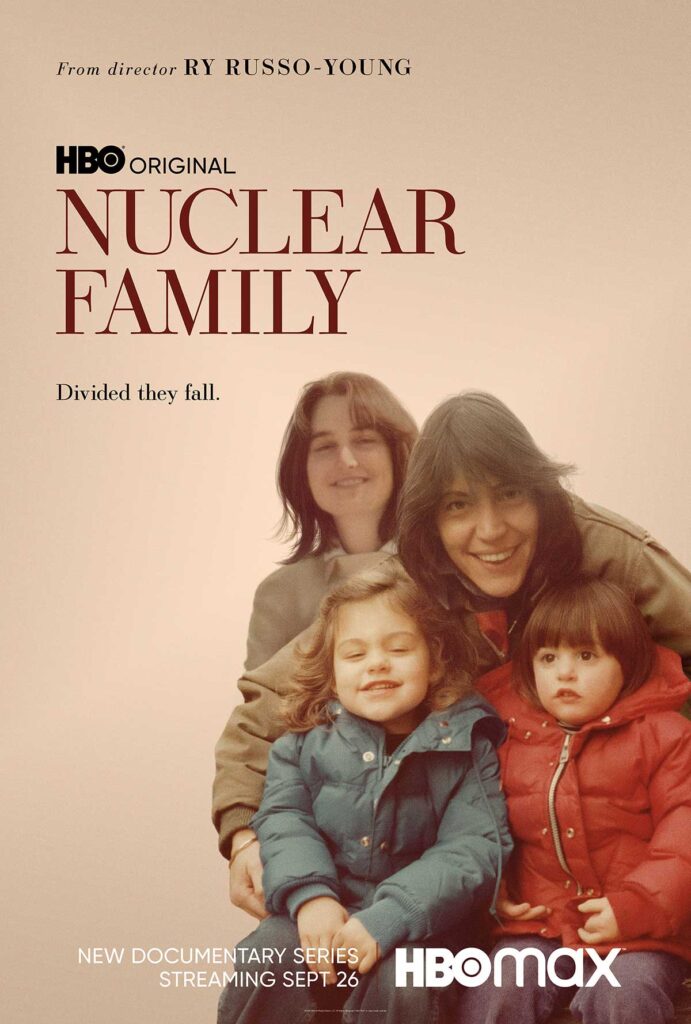

It is many a queer parent’s nightmare: your child’s sperm donor sues for paternity. When it happened to Robin Young and Sandy Russo in 1991, it precipitated a landmark four-year court battle that indelibly marked 9-year-old Ry Russo-Young and her 11-year-old sister Cade. Yet Ry, now an award-winning filmmaker, had never been able to really process her feelings about what happened. Her quest to do so, and to understand the other side of the story, led her to create “Nuclear Family,” a three-part documentary that premieres this week on HBO.

The film is a family story, a personal quest for understanding, and a piece of LGBTQ parenting history. Ry weaves segments of home videos together with interviews of her moms, friends of the family and the donor (including the mutual friend who introduced him), and lawyers on both sides, along with television clips, her own commentary, and more, to create a film that offers a nuanced look at what it means to form, nurture, and protect our families.

Young and Russo told me via e-mail, “Ry’s film shows how important it is to know our own history and to live our lives openly and honestly so others have the courage to openly live their truths.”

Their family’s story begins in 1979, when the two women met, fell in love, and got an apartment in New York City. They were among the first wave of lesbian couples to start families together, when there were almost no medical or legal supports. They learned how to do at-home insemination by reading a hand-drawn, mimeographed pamphlet from a women’s bookstore.

The couple thought that a gay donor would be sympathetic to what they were trying to do, but did not want him to have any rights over or responsibilities for the child. A friend suggested someone she knew. Russo got pregnant on the first try, and she and Young welcomed their first child, Cade. They chose a different donor for their next child, though, so that no one man would have too much potential power over their family. The same friend suggested another man she knew, attorney Tom Steel. Soon, Young was pregnant, and gave birth to Ry in 1981.

The family was in many ways very traditional; Russo worked, Young stayed home with the kids, and there was a lot of fun and a lot of love. Russo and Young were always honest with the children about how they were created. When Cade was in preschool, she said she wanted to know more about her donor. The moms were amenable; Russo was especially willing to help them connect because she had never known her own father and didn’t want her children not to know the men who helped create them, even if they didn’t think of them as fathers.

Both donors became friends of the family and would visit occasionally. Cade’s donor faded from their lives, but sometimes Steel, the moms, and kids would rent a vacation house together. Eventually, though, as Russo and Young tell it, the relationship became tense as the moms grew afraid of Steel’s deepening closeness with Ry to the exclusion of other family members.

In 1991, Steel unexpectedly sued them for paternity and visitation rights over her.

The lawsuit, court appearances, psychological evaluations, media scrutiny, and potential for family upheaval that followed were traumatic for both children and underscored the fragility of their family at a time when lesbian mothers were still often seen as unfit by the courts. Russo had no legal rights over Ry and was not even allowed into the courtroom. It would be easy to view Steel in purely unflattering terms.

In the film, though, we see Steel’s friends, colleagues, lawyers, and partner’s son (from a previous relationship) paint a picture of a man who genuinely loved Ry and wanted to maintain their relationship, especially after his health began to deteriorate from AIDS complications. (He died in 1998.) Ry herself had “fond memories” of his visits. Simultaneously, though, her moms were understandably protective of the family they had worked so hard to build and afraid of how the lawsuit could destroy their identity as a family of four.

One message of the film, then, is that while we may not always agree with someone — may even have anger towards them — we can always seek to understand them better. In doing so, we might also come to better understand ourselves.

Russo and Young have been changed by the film, too. They told me, “Our conversations with Ry and her sister Cade have always been open and loving. In the process of making the film, we came to a deeper understanding of both Ry and Cade’s experiences around the lawsuit and we all grew even closer.”

On a broader level, Nuclear Family reminds us how much positive change there has been for queer families over the past four decades—but also why we need to keep addressing the inequalities that remain. As Russo and Young said, “We think the important message in Ry’s film is that all families deserve respect, recognition, and legal protection. Families come in all shapes and sizes and it is our right to self-define these relationships.”

“Nuclear Family” is highly recommended viewing not only for queer people but for anyone interested in what it means to be a family. Watch on HBO and HBO MAX, starting Sunday, September 26 at 10 p.m. ET and then weekly.

Dana Rudolph is the founder and publisher of Mombian (mombian.com), a GLAAD Media Award-winning blog and resource directory, with a searchable database of 750+ LGBTQ family books, media, and more.