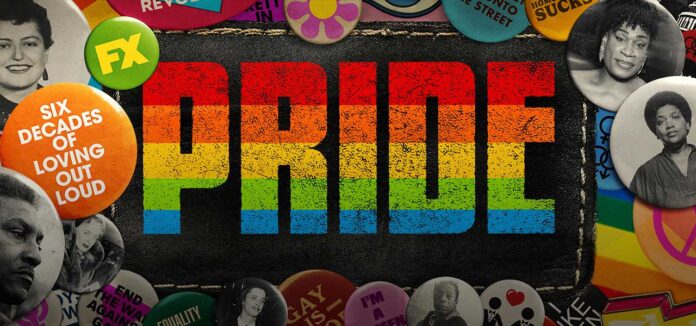

FX’s documentary series “Pride” is above all things a labor of intense love and devotion to LGBTQ history. Six documentaries by seven filmmakers cover each decade from the 1950s through the 2000s, with the last film covering the present as well.

The series is produced by Vice and lesbian filmmaker and producer Christine Vachon’s Killer Films. The films are 1950s: People Had Parties, by Tom Kalin; 1960s: Riots & Revolutions, by Andrew Ahn; 1970s: The Vanguard of Struggle by Cheryl Dunye; 1980s: Underground by Anthony Caronna and Alex Smith; 1990s: The Culture Wars by Yance Ford; and 2000s: Y2Gay by Ro Haber.

These are intriguing evocations of the time before and after Stonewall. As one historian notes in Kalin’s powerful look at 1950s queer life, LGBTQ people didn’t all hate themselves and hide their existence from the world and each other before Stonewall.

In fact, Kalin’s re-telling of the Lavender Scare period is immensely engaging and feels like a look behind doors that have been closed to us in previous histories. The archival footage of gay men having fun at parties and at the beach is somehow freeing: knowing these people weren’t living in abject misery as we’ve been told by mostly straight historians is a relief.

But it’s not all fun and frolic. Along with the sweetness of photos of Black and white servicemen posing in loving embraces and kissing for the camera in those old photo booths are the stories of the McCarthy era and President Eisenhower’s horrific Executive Order 10450.

Kalin details two stories to explicate the impact of the Lavender Scare and the power of Sen. Joe McCarthy (R-WI): Madeleine Tress and Sen. Lester Hunt (D-WY). Tress was fired from her government job for being a lesbian. Hunt committed suicide in his office in 1954. Hunt had been blackmailed by McCarthy after his son was arrested in a gay sting in Lafayette Park.

Kalin balances re-enactments of these two stories with interviews from Lester Hunt’s granddaughter and Tress’s gay younger brother. This is history made deeply personal. Also in this segment is Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), the first out lesbian senator who now sits in McCarthy’s old seat.

“Pride” is told from a different vantage point from most documentaries of LGBTQ history. While three of the filmmakers are white gay men, the other filmmakers are all people of color. In addition, Ford is a trans man, Haber is non-binary. Dunye, who lived in Philadelphia for long enough for many to claim her as our own, is the only lesbian filmmaker.

(One overall complaint is there should have been more lesbians and female perspectives in these six films. Also the 2010s to the present would have benefitted from its own film — a lot happened between 2000 and 2021.)

Those used to viewing the LGBTQ movement through the eye of whiteness and maleness may be discomfited by a lot of what is seen here. But this series is an opening up of our collective story as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer and non-binary people and as such is more inclusive of the range of our radical history.

As a consequence, in the 1960s story, the link between the Black civil rights movement and the gay liberation movement is made by through the story of Bayard Rustin, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s lieutenant and an openly gay man. Rustin was the architect of the 1963 March on Washington. But because Rustin had been arrested for indecency after being caught in a car with another man, he was relegated to the background.

Also in this segment is a series of actions by unnamed gay and trans activists who fought back against police — including in Philadelphia at Dewey’s.

On April 25, 1965, the first of two historic sit-ins occurred at the popular after-bar hangout, Dewey’s restaurant at 17th and Chancellor. One of the earliest demonstrations advocating for the LGBT community in U.S. history, it began as a fight with police over dress codes among lesbians and trans women.

Ahn’s 1960s film also focuses on drag and ball culture, using a lot of found footage from the 1967 film The Queen. Philadelphia’s own Harlow is a figure in this sequence. Other Philadelphians who appear in this film are Barbara Gittings marching for gay rights and historian Marc Stein whose work is archived at the William Way Community Center.

Dunye uses her film to tell the story of how lesbians built second wave feminism and then were excised from it by Betty Friedan and other straight women. Her film is one of the most cohesive, using archival footage and interviews to tell the stories of renowned filmmaker Barbara Hammer and poet and essayist Audre Lorde and what their work means.

Dunye frames these two iconic figures amid interviews with women of that era like writers Barbara Smith and Cheryl Clarke, historian and activist Karla Jay and Hammer’s wife, human rights activist Florrie Burke.

Friedan isn’t the only villain of the piece. Dunye uses compelling archival footage of Phyllis Schlafly and Anita Bryant to highlight how lesbianism was linked to feminism and the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and how that led inevitably to anti-gay initiatives in California and Florida.

There is satisfying footage of Bryant getting a pie in the face and weeping as she prays for the gay activist who did it and deeply moving footage of the vigil for Harvey Milk where the candles seem to go on forever.

Found footage in Ford’s film pivots out of that rise of the religious right that began in the 1970s and blew up in the 1980s and 1990s. There is a stunning segment with gay director Todd Haynes and Christian Coalition leader Ralph Reed, moderated by Bryant Gumbel on the “Today” show.

This is such a compelling history with Haynes, an out gay director debating with Reed, who was obsessed with the “obscenity” of openly queer depictions in film and other popular culture. Reed was such a pivotal figure in 90s politics. All this on morning TV.

The 1980s film utilizes extraordinary footage — culled from over a thousand hours — shot by New York gay scene videographer Nelson Sullivan from 1982 until his sudden death from a heart attack on July 4, 1989, at 41.

Sullivan filmed his cross-dressing drag queen friends as well as his friends in gay New York like RuPaul, Lady Bunny, Michael Musto and Keith Haring.

AIDS is the main story of the 1980s and it is an unrelenting tragedy, so these other pieces gleaned from Sullivan’s footage read as a relief as well as their own historical context.

The final film by Haber ends with scenes from the march for Black trans lives in Brooklyn last summer. This takes the viewer far from the opening scenes in the 1950s and also makes it abundantly clear how LGBTQ people are still fighting for our very lives.

Compelling as it is, “Pride” should be viewed in bites rather than as a binge-fest so as not to miss anything. There are myriad interviews with historians, writers, activists and victims of homophobia and transphobia. Some of the films are more successful than others, and not all of the techniques work. Some voices are far too present (Republicans, Bill Clinton and some historians) and others not present enough (lesbians, Latinx people).

Yet this is a series that takes the viewer on a journey that is largely new. These are not santitized nor wholly cisgender takes. The sometimes uneven content and storytelling of these films speaks to the fact of our disjunctive and often disconnected quest for civil rights, which makes it an honest tale of our authentic lives.

“Pride” airs on FX and Hulu.