The 2003 landmark Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas struck down sodomy laws nationwide and decriminalized private sexual conduct between same-sex people in all 50 states. But as early as 1962, individual states, starting with Illinois, began their own dismantling of sodomy laws. Pennsylvania’s sodomy laws were struck down in 1980, over twenty years before Lawrence. Yet the case that spurred the state’s decision to decriminalize private same-sex sexual activity, Commonwealth v. Bonadio, isn’t what one might have expected: it involved sexual activity between heterosexuals.

In March 1979, police raided the Penthouse Theater in Pittsburgh and arrested two dancers, Mildred Kannitz and Shanne Wimbel, who engaged in oral sex with members of the audience. Two theater staff, Patrick Gagliano and Michael Bonadio, were also arrested. The staff members were charged with criminal conspiracy and the dancers were charged with voluntary deviate sexual intercourse, which was defined as “sexual intercourse per os or per anus between human beings who are not husband and wife.” Many in the gay community had also been charged with the same crime.

Attorneys for the four filed a motion in the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas to dismiss the case, arguing that the voluntary deviate sexual intercourse statute was a violation of privacy. The judge, George Ross, dismissed the case in July 1979. Ross found the statute unconstitutional on two grounds: it violated an individual’s right to privacy and it denied equal protection of the law to unmarried people.

Soon after Judge Ross’ dismissal of the case, Robert Colville, the district attorney of Allegheny County, appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, who heard arguments in March 1980. The American Civil Liberties Union, the National Committee for Sexual Civil Liberties, and the Eromin Center submitted amicus briefs in support of the case’s dismissal.

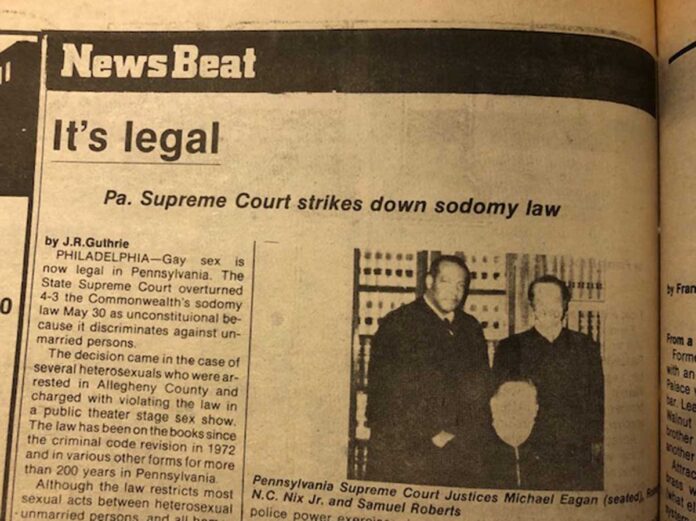

Two months later, the Court, in a 4-3 decision, ruled the sodomy law unconstitutional.

Justice John Flaherty was joined by Justices Michael Eagan, Rolf Larsen and Bruce Kauffman in the majority. Justices Robert N.C. Nix, Jr., Henry O’Brien, and Samuel Roberts dissented.

In the majority opinion, Flaherty wrote “The Voluntary Deviate Sexual Intercourse Statute has only one possible purpose: to regulate the private conduct of consenting adults. Such a purpose, we believe, exceeds the valid bounds of the police power while infringing the right to equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States and of this Commonwealth.”

Flaherty went on to write that “to suggest that deviate acts are heinous if performed by unmarried persons but acceptable when done by married persons lacks even a rational basis, for requiring less moral behavior of married persons than is expected of unmarried persons is without basis in logic. If the statute regulated sexual acts so affecting others that proscription by law would be justified, then they should be proscribed for all people, not just the unmarried.”

Flaherty also noted that the sodomy laws should not be used “to enforce a majority morality on persons whose conduct does not harm others,” and he called out people who enforce similar laws on moral or religious grounds.

“Many issues that are considered to be matters of morals are subject to debate,” Flaherty wrote, “and no sufficient state interest justifies legislation of norms simply because a particular belief is followed by a number of people, or even a majority. Indeed what is considered “moral” changes with the times and is dependent upon society background. Spiritual leadership, not the government, has the responsibility for striving to improve the morality of individuals. Enactment of the Voluntary Deviate Sexual Intercourse Statute, despite the fact that it provides punishment for what many believe to be abhorrent crimes against nature and perceived sins against God, is not properly in the realm of temporal police power.”

It is worth noting that Flaherty did provide a slight wiggle room for those who wanted the laws to be upheld: ban the same sexual activities for married people. However, no such endeavor was ever conducted.

In his dissenting opinion, Nix wrote: “Concern over the marital exception contained within the voluntary deviate sexual intercourse statute is misplaced, for the heart of this exception is the intimacy and warmth of a private marital sexual relationship. Here, the sexual acts were performed in public and in return for monetary compensation. It is therefore clear that the marital status of the participants in this conduct would not have affected their culpability. To suggest that the marital exception was intended to insulate a marital couple who performed deviate sexual acts for public display for pay would distort the obvious legislative objective in providing for this exception. The marital exception was designed to protect the intimacy and privacy of the marital unit. It did not give married couples the license to publicly engage in lewd and lascivious public acts.”