The modern LGBTQ civil rights movement was born out of police harassment and brutality against a group of gay men, butch lesbians and trans women of color. Most queer and trans people know about the Stonewall Uprising in June 1969; it’s why we celebrate Pride Month.

We know that some leaders of that event were regular targets of police violence. Stormé DeLarverie was the butch lesbian whose scuffle with police was, according to eyewitnesses and noted in many histories of the event, the spark that ignited the Stonewall riots, spurring the crowd to action. As a lesbian of color who was gender nonconforming, she said she faced police harassment often.

Trans women Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera have recently been memorialized for their later role in the uprising with a statue in New York City — the “first permanent, public artwork recognizing transgender women in the world,” according to the Smithsonian. Johnson and Rivera were both arrested often, and Johnson spoke at length about her experiences with law enforcement.

The history of police violence against LGBTQ people in Philadelphia is long and ugly. Nearly every LGBTQ person I know, regardless of age or identity has experienced it in some form, either in dismissive responses to reports of hate crimes to just casual comments while on the street in the Gayborhood or elsewhere. From the 1960s to 1980s, police raids on the bars were frequent and brutal.

Several investigative series I have reported in recent years for PGN have highlighted how LGBTQ people in mental health crises or trans women of color sex workers who have been attacked by clients have been treated by police. It’s a grim picture — and it’s not a moment in past history: these series are from 2020, 2019 and 2016.

My own early experience with police as a teenager in the local gay bars and clubs around 13th and Locust was fraught with harassment and violence. And as an AIDS activist in the 1980s and 1990s, I experienced abusive treatment by police on a regular basis, as did most of my fellow activists.

After I was brutally raped a few years ago by a serial rapist preying on women during his lunch hour in my neighborhood, I wrote about my shocking experience with SVU detectives for Huffington Post and Curve magazine.

The harassment and violence against LGBTQ people by police certainly didn’t stop at Stonewall. We just stopped talking about it. Study after study has shown that LGBTQ people — particularly gender nonconforming lesbians, trans women and queer people of color — face continued harassment and violence from law enforcement.

Gay men I have interviewed who have reported their experience with hate crimes attacks have disclosed abusive and dismissive treatment by law enforcement that has ranged from insensitive remarks to outright hostility and an attitude that they brought the violence on themselves.

Stephanie Schroeder, a lesbian who has written extensively about mental health issues in the LGBTQ community, told me in a series of interviews for PGN and other publications about the layers of abuse and violence mentally ill LGBTQ people have experienced from law enforcement. And an investigative piece I did for the Stanford Social Innovation Review in 2019 enumerated how mentally ill LGBTQ and people of color are warehoused in jails and prisons.

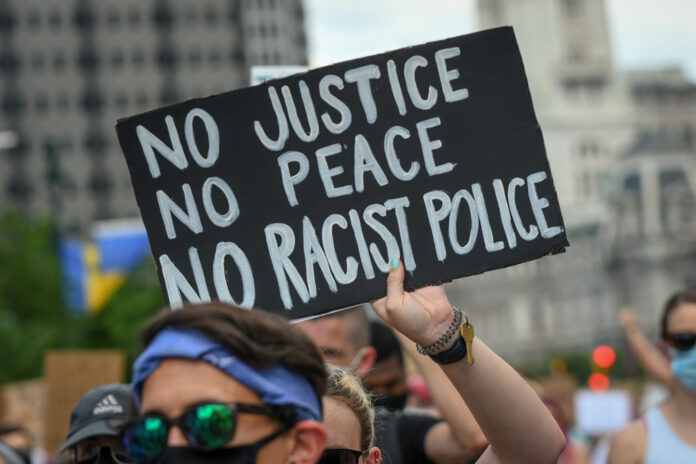

Police have a long history of targeting queer and trans people and invading LGBTQ spaces to harass and harm us. The reckoning those of us who are racial justice activists hoped would come from the summer of 2020 protests has not materialized.

Structural racism and structural misogyny are built into policing. How else to explain that in a country known for being carceral, with more than two million people in jails and prisons in the U.S., fewer than five percent of rapists are prosecuted and only one percent are convicted, yet one in five women — with LBT women disproportionately represented among them — is a rape victim?

The 2020 protests didn’t just detail how much violence is perpetrated by police against marginalized groups — it replicated that violence. How many Philadelphians marching for justice were pepper sprayed, tear gassed and beaten by police? How many were young queers of all races?

If we weren’t there in person during the protests, we witnessed these events on our local TV news every night. Yet was anyone prosecuted, fired or even suspended? No.

The failure of law enforcement to protect LGBTQ people against violence from the community is also a failure to police themselves. The protests sparked by George Floyd’s murder and the killing of Breonna Taylor exposed decades-long patterns of police brutality and how marginalized groups are disproportionately harmed by the criminal justice system.

On April 13, Rep. Malcolm Kenyatta, who is running for Pat Toomey’s U.S. Senate seat next year, and who is one of only two out gay members of the Pennsylvania state assembly, tweeted, “It’s traumatizing to see so much Black pain. These tragedies aren’t sad hypotheticals for me. They’re the reality I grew up and live in.”

On April 12, Michigan Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib said, “Policing in our country is inherently and intentionally racist…. I am done with those who condone government funded murder. No more policing, incarceration, and militarization. It can’t be reformed.”

Tlaib, a staunch progressive, has gotten pushback on that messaging, but for many LGBTQ people, it sounds accurate and true to our experience. Reports from the ACLU and Lambda Legal, as well as studies from HRC and the Williams Institute at UCLA all concur: LGBTQ people aren’t safe from police and experience harassment and mistreatment, including violence, from law enforcement.

Part of that violence against LGBTQ people means we are overly incarcerated, often for minor crimes. LGBTQ people are targeted by police, and that often lands them in jail or prison. Gay and bisexual men are disproportionately represented in the prison population. More than 40 percent of women who are incarcerated identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, compared with only 5.1 percent of all US women.

The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey found 2 percent of the transgender population had been to prison or jail — nearly double the share of cisgender people in the U.S.

Less than 10 percent of all American youth identify as queer, but in 2017, 20 percent of youth in juvenile justice facilities were LGB. Eighty-five percent of incarcerated LGBT and gender nonconforming youth were people of color.

According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, while incarcerated, more than 30 percent of LGBTQ people experience sexual victimization, compared with only 8 percent of heterosexual people.

Transgender people who are incarcerated are five times more likely to be assaulted by correctional staff and nine times more likely to be assaulted by other incarcerated people.

Although there are not clear data on the exact rates of infection among LGBTQ people who are incarcerated, many are likely exposed to the coronavirus because of their overrepresentation in prisons and jails and LGBTQ people have more fragile health than their non-LGBTQ peers.

In a tweet on April 13, Kenyatta said, “It’s okay to be scared, sad, angry, or depressed. In moments like this we need community more than ever. You aren’t alone.”

We indeed have each other — and elected officials who care about us like Kenyatta, Tlaib and others — but as these stories illumine, we need so much more.