We’re coming off a historic year in 2020. A year that devastated us and empowered us. A year that tested us and made us stronger. A year that put systemic racism and health disparities front and center for the world to see. It reminded us that there is still much work to be done in the fight for equality and equity, and it also inspired us to act toward progress.

We are still in the middle of a pandemic that has claimed the lives of over 500,000 Americans, but amid the struggle we are beginning to see a light at the end of the tunnel. As the COVID vaccine allows us to feel hope, I reflect on what this feeling must be like for long-term survivors of HIV. Many remember when a new unknown virus emerged that was claiming the lives of their loved ones. A virus that they still live with today.

As we work to manage the current pandemic, many who have been living with HIV for decades once again find themselves losing loved ones. Reliving the past, grateful for what science has brought so quickly, and cautious to not let history repeat itself.

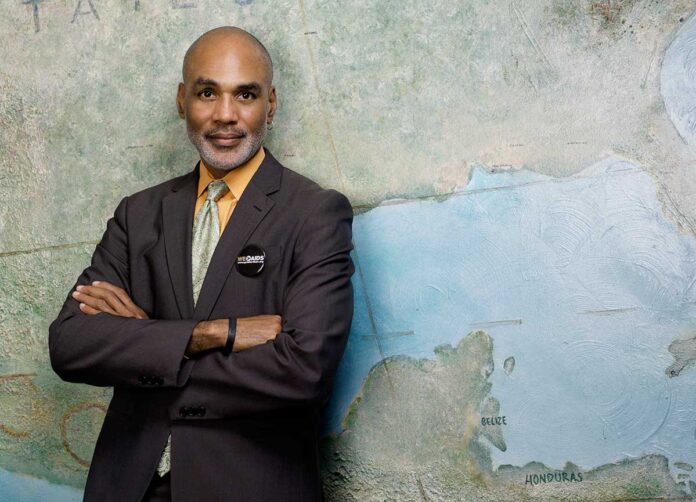

I recently had a conversation with Phill Wilson, founder and former CEO of the Black AIDS Institute. As many know, Phil is a gay Black man who has been living with HIV since 1981. He has been a champion and leader in this work for decades and understands better than anyone the concerns facing people living with HIV and the parallels to COVID, especially in Black communities. He says:

“This experience presents both an emotional as well as a physical health risk. We’re living dual experiences because we’re not yet finished with the HIV pandemic, and we’re now living with COVID. There is kind of a painful déjà vu going on as COVID-19 is manifesting itself in our communities in the way HIV continues to manifest itself in our communities. Chief among them are the disparities. Black communities were slow to respond to the HIV/AIDS pandemic while we were disproportionately impacted, and policy makers were not sufficiently concerned about our needs. That is being replayed with COVID-19 as well.”

It should be very apparent at this point that ending HIV and COVID-19 is about more than just access to medicine and vaccines. It’s about dismantling the systems of oppression that allow these viruses to thrive and recognizing that Black and other marginalized communities have a long history of distrust of the medical system. Many remain traumatized by the Tuskegee experiment, Henrietta Lacks, the experimental procedures performed on enslaved women, and the list goes on.

“Black people have very legitimate reasons to have medical mistrust because the medical community has not always been responsive to our needs,” Wilson says. “The most dominant way we have been mistreated by the medical community is by them withholding treatment from us.” Tuskegee is an example of that, as the Black men involved received no treatment for syphilis, and Wilson believes that is exactly why we should be fighting for information and access to the vaccine now.

I wholeheartedly agree with him and at the same time understand that as much as I urge Black communities to get into HIV care, utilize PrEP and take the COVID vaccine, I know it’s not that simple. Medical racism is real, and the challenge is on America to overcome it. We can urge people to take this vaccine without shaming them or judging them for being skeptical. It’s not Black people’s fault that they don’t trust the medical system. America has been medically unethical since the founding of this country. That legacy never goes away.

Therefore, my job and that of everyone who calls themselves an advocate or is a part of the medical system in any way is to improve trust by providing equitable care and accurate information that allows people to make informed decisions about their health. We need all of us collectively working together. So many people have already lost their lives. Wilson cautions us to not repeat past mistakes, saying:

“These are lessons that we’ve learned and, frankly, the consequences of screwing up. I’m hoping we can take the lessons of HIV/AIDS, apply them, and come up with more equitable solutions as we fight the pandemic. And one of them is making sure that medicine, vaccines, and prevention tactics and strategies are open and accessible to Black, brown and other marginalized people.”

Simply put, we honor the past by fighting for the now, fighting for the future. Let’s ensure we all survive.

Ashley Innes is a writer and HIV advocate. Follow her on Twitter @Ash_Innes. This column is a project of TheBody, Plus, Positively Aware, POZ and Q Syndicate, the LGBTQ+ wire service. Visit their websites – http://thebody.com, http://hivplusmag.com, http://positivelyaware.com and http://poz.com – for the latest updates on HIV/AIDS.