In this era of so-called “cancel culture,” and one in which news outlets close every day, the 45th anniversary of an independent newspaper is, as President Biden might say, a “big f-ing deal.”

I have been working for PGN on and off since I was a 17 year old college student — as a freelancer, as a staff reporter and as an editor. PGN is where I learned how to be a reporter. Working for PGN as a staff reporter in my early 20s, doing both beat reporting and investigative work, is also what propelled me into mainstream journalism as a reporter for daily newspapers and national magazines.

Yet some of the award-winning work I have done at PGN has been among my very best. There are investigative series I’ve done for this paper that I am deeply proud of, which were groundbreaking journalism and which illumined crucial LGBTQ stories no one else was telling.

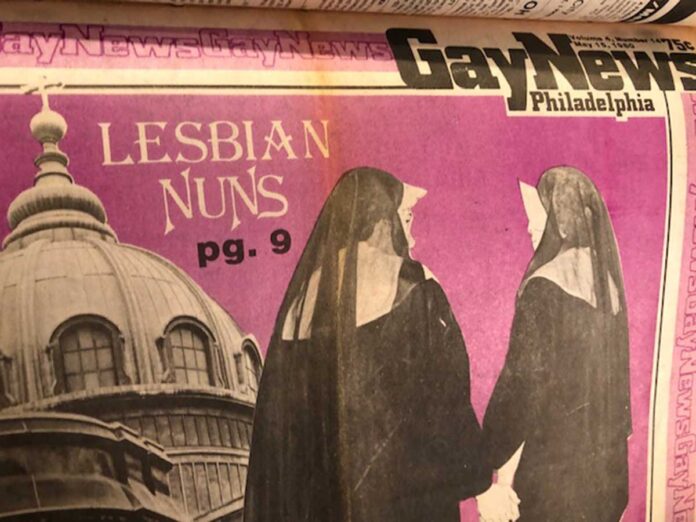

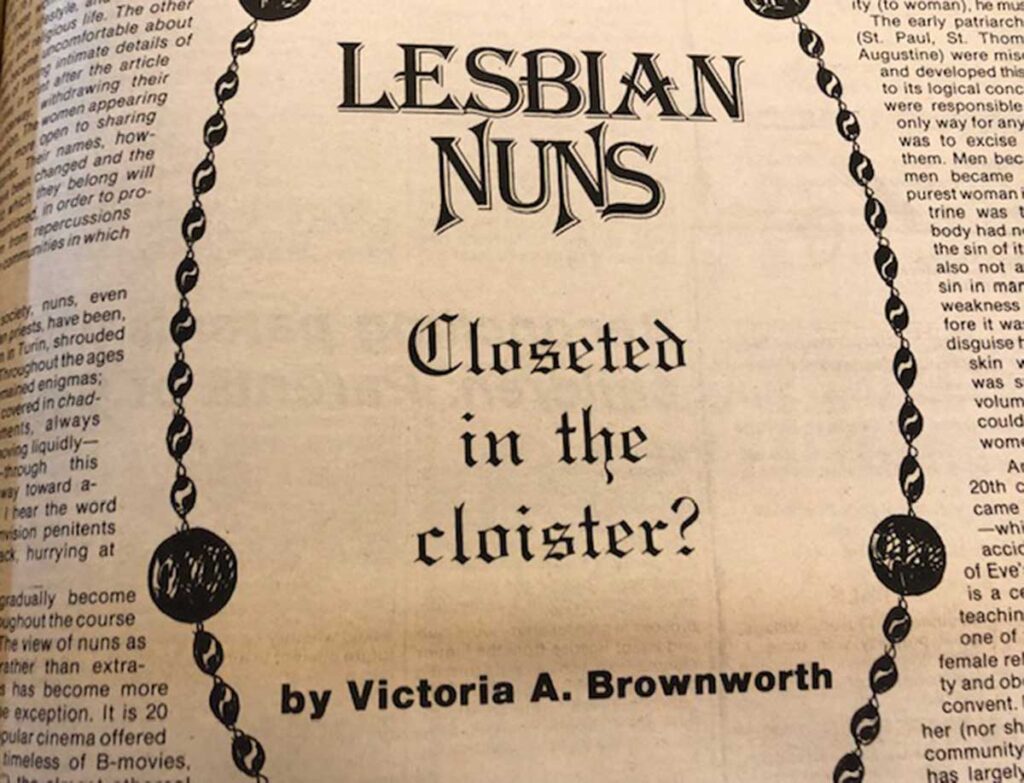

Lesbian Nuns

I had just moved back to Philadelphia from a stint in the domestic Peace Corps when Mark Segal approached me to do what he thought — rightly — would be a groundbreaking series: lesbian nuns. It was pure Mark Segal: “You’re a Catholic, right? You must know some lesbian nuns. Write a story about it. I may have a contact.”

The series is footnoted in the highly controversial 1985 book “Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence,” edited by former nuns Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manahan. Manahan said at the time that the series helped propel the book.

Among the women I interviewed was a nun who had taught me in Catholic school. Another was lesbian activist and Chicana writer Jeanne Córdova. The controversy spawned by my series and later, the book, pushed me into the TV talk show circuit as what producers began to call The Lesbian in a Dress.

Exodus and the Ex-Gay Movement

Throughout the 1980s I appeared on myriad local and national TV talk shows as a PGN reporter, because the work I was doing was pushing buttons as well as envelopes. I covered the burgeoning “ex-gay” movement — a movement former Vice President Mike Pence supported. TV producers were only too happy to stoke ratings by putting a pretty 20-something lipstick lesbian who was happily gay on TV with “Philadelphia Gay News reporter” under her name on the chyron and pit her against dour, unsmiling ex-gay men and women claiming homosexuality could be “cured.”

At PGN I exposed a lot of the ex-gay crowd, like those running the group Exodus, and their pattern of using the dangerous pseudoscience of conversion therapy, also called reparative therapy.

As recently as 2019, I covered the Philadelphia Archdiocese — emboldened by the Trump administration and still led by the virulently anti-LGBTQ Charles Chaput — featuring an ex-gay ministry through its education services. In the past couple years I have written about how conversion therapy is still legal in most states and all but six countries in the world.

It was the lesbian nuns series that had led me back to PGN where I had been a freelancer during my college years. In the early 1980s, after my Peace Corps stint where I also freelanced for daily newspapers in Louisiana and Mississippi, I became a staff reporter at PGN. I was doing local and national stories, working with legendary editor Stan Ward and one of the best beat reporters I’ve known over the years, Tommi Avicolli Mecca. Tommi had originally introduced me to PGN when we were both students at Temple University.

AIDS

At PGN in the 1980s, AIDS was the story. I was reporting on every aspect of the AIDS crisis when AIDS was still considered mostly a niche gay story. I was literally the only woman reporter covering AIDS at that time, frequently the only woman in the room at major events.

For PGN I covered the press conference for the announcement of AZT, the first drug in the AIDS arsenal. But because my editor wanted to change things up and have PGN do stories no one else was doing, I was also at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, holding AIDS babies in their special unit. I was talking to people with AIDS in Belle Glade, Florida, which in 1985 had the highest per capita number of AIDS cases in the world.

Locally, I was holding hands covered with Kaposi’s lesions as I interviewed people with AIDS in a hospice I was investigating for abuse, trays of open rat poison positioned all over house where gaunt men in their final months and weeks were dying, talking to me about all the abuses there in the place that was supposed to be their refuge.

I also interviewed many of the major American players in the AIDS fight, among them AZT co-creator Dr. Sam Broder, San Francisco AIDS researcher and iconoclast Dr. Paul A. Volberding, AmFar founder Dr. Mathilde Krim, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. C. Everett Koop, and ACT UP founder Larry Kramer. Throughout those early years of the epidemic, I wrote obituaries of men who were famous and men who weren’t, but all of whom had died of the disease.

I reported on that darkest of times in queer history as both a journalist and an activist. I covered AIDS conferences in New York, Washington D.C., Boston, Miami, Los Angeles and San Francisco even as I was a member of ACT UP and participating in die-ins and other protests.

No other newspaper would have let me do both things; PGN did and it made my reporting better, richer, more vivid. Laying in the street, chanting in front of the Reagan White House, being put in police vans by cops wearing blue gloves afraid to touch us, you see a different side to the story you are reporting.

And conversely, covering the stories I did — like the investigation of that hospice for people with AIDS in West Philly — made me all the more devoted to AIDS activism.

U.S. Supreme Court

Stan Ward also assigned me to cover the U.S. Supreme Court. For three years I was the first out queer reporter covering that beat. I sat in the press box with the mainstream press heavyweights and witnessed the iconic Thurgood Marshall, William Brennan and Harry Blackmun on the bench. The U.S. Supreme Court did not allow cameras — it still doesn’t — which made our role as reporters all the more critical. And my press credentials around my neck read “Philadelphia Gay News” at a time when the queer press was yet to be acknowledged by the mainstream. The LGBTQ perspective was new and crucial.

I spoke with Harry Blackmun briefly after the pivotal Bowers v. Hardwick case in 1986, which upheld the Georgia sodomy statute and thus all sodomy statutes. Blackmun was furious about the decision, which he thought was wrong and which he also thought undermined his 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade.

Blackmun insisted that the court — the majority opinion was written by Justice Byron White — was “almost obsessively focused on homosexual activity.”

Blackmun said in his dissent, “Only the most willful blindness could obscure the fact that sexual intimacy is ‘a sensitive, key relationship of human existence, central to family life, community welfare, and the development of human personality.’” He echoed those points in talking about the case outside the court that day in the blazing heat.

Eromin Center

A story that signaled PGN as one of the most vital and serious newspapers of record for the LGBTQ community was the Eromin Center scandal. I was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for my investigative reporting of the story, my first nomination for the prestigious award. It began one weekend when I was with friends at a restaurant in New Hope. A woman came up to me and asked me if I was Victoria Brownworth, the Philadelphia Gay News reporter. She had seen me on TV.

She was a whistleblower who wanted to tell me a story of financial mismanagement, kickbacks and other, darker corruption at the Eromin Center, which provided mental-health services for sexual minorities and crucial care for LGBTQ youth.

Founded in Philadelphia in 1973, the Eromin Center was one of the first organizations in the country to provide non cure-driven mental health services to sexual minorities. But the story I broke was one of fiscal misappropriation and skimming, as well as rumored juvenile prostitution.

The shockwaves through the community as I investigated the story, interviewing myriad off-the-record sources, went wide and deep. One afternoon, a couple of well-known members of the community, checkbooks in hand, came to a meeting they’d requested at the PGN office.

Once again I was the only woman and the misogyny ran thick as they offered to buy out the issue of PGN where my sprawling 8,000 word story was scheduled to headline the paper. They also threatened to sue me — “that woman, that yellow journalist” — and the paper (one of the people later did sue me for slander and lost).

Needless to say, Mark Segal refused their offer.

The story was huge, as was the impact. As a result of my work, Eromin Center fired its executive director, Tony Silvestre, on Aug. 29, 1983. The board later cited “financial-management problems” and went on to fire its administrative director, Lisa Segal.

My investigative series found the agency owed back taxes of more than $50,000 and was facing an IRS lien. The center’s members voted out the board’s executive committee in September. In the ensuing months, the city launched an audit of the organization’s finances and subsequently suspended its city contract, as another aspect I uncovered was so-called “double dipping” between City Hall and Eromin. The agency closed the following year.

Homeless LGBTQ Youth

Some stories are brutal to cover. In 2008, while I was working for a daily newspaper, a close friend who was a social worker said I should be writing about homeless LGBTQ youth, a problem she said was “exponential” in Philadelphia. It wasn’t a story my straight editors were interested in covering. Queer stories had remained largely niche in mainstream journalism, outside the battles for marriage equality and serving openly in the military, both stories that were heating up in 2008, an election year.

My four-part series, Hiding in Plain Sight, begins:

Justin is cold.

It’s past midnight and we are sitting on a bench in Washington Square. His hands are clasped around the coffee I bought him at the convenience store a few blocks back.

‘In the summer I always thought it was too hot at night,’ he says ruefully. ‘Now it’s going to be too cold. Too cold already. I gotta get out of here.’

But Justin doesn’t really have anywhere to go, tonight or any other night, regardless of the weather. Justin is homeless.

For weeks I camped out nights in Washington and Rittenhouse Squares, walked through the then-open subway concourse and along the pathways of Judy Garland Park, and bought a lot of meals for teens with nowhere to go. A few dawns I found myself waking up on a park bench where I had fallen asleep myself. Other nights I spent talking to people in the dank, urine-soaked catacombs of the concourse.

Young queer girls were working in massage parlors while boys were hanging out on the Center City Merry-Go-Round and Judy Garland Park and the Squares. The story was one of despair and danger, with kids living any way they could as they struggled to survive after being rejected by their families of origin for being queer or trans. Some already had HIV, others were substance abusers. Some local social services organizations tried to help, but the need was great and the services limited.

The series won first place for enterprise reporting from the PA Newspaper Publishers Association Keystone Press Awards and remains one of the most haunting I have covered. It also led to a series on LGBTQ suicide for which I won the NLGJA Award the following year. Those kids will never recede from my memory. We still have so much work to do within our own community.

I have written well over a thousand stories for PGN since the late 1970s, some of them uniquely powerful. I returned to PGN a few years ago after a long hiatus where I was writing books and reporting for the mainstream press. In this latest iteration I have done stories on the hidden horrors of LGBTQ domestic violence and LGBTQ poverty. I have exposed the disgraceful treatment of disabled LGBTQ people in another series that was nominated for several national awards. I have written about LGBTQ elders, and for the 50th anniversary of Stonewall I did a 12-part series on 12 groundbreaking Philadelphians and others who changed history in the early pre-Stonewall years.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and USAID

In 2019 and 2020, after having been assigned the international beat, I wrote a series of stories exposing how then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was remaking and reframing the State Department and USAID as anti-LGBTQ agencies and influencing geopolitics in that radical evangelically driven direction.

With a budget of $42 billion, this was a major enterprise, and Pompeo commissioned studies, enjoined panels and even created his own anti-LGBTQ position papers signed onto by some of the worst anti-LGBTQ countries in the world.

While PGN has focused mostly on local stories, this international story of Pompeo using his power to advance his anti-LGBTQ agenda was major news, and covering it was crucial. As recently as Nov. 4, 2020 — Pompeo was doing this work right up to the election — I reported on Pompeo’s Geneva Consensus Declaration. Pompeo engaged 32 member states in the United Nations, many of which are authoritarian regimes or considered flawed democracies, as signatories in a dangerous anti-LGBTQ agenda that the Biden administration will have to rescind.

45 Years Later

The stories I have covered in PGN over decades, only a handful of which I have written about here, have been defining. Last week I wrote three stories: about the impact of COVID on poverty in the LGBTQ community; about the plethora of bills in the states to undermine LGBTQ equality; and the way the GOP legislature in Pennsylvania is attempting to suppress our votes. These stories are as critical to our LGBTQ lives as the stories I first covered nearly 40 years ago as a budding reporter when the AIDS epidemic was just beginning.

The need for independent journalism in the U.S. has never been greater. And the need for an LGBTQ press has never ceased to be critical in the decades since Stonewall. PGN continues to prove that necessity every week — and those of us reporting on the stories of our queer and trans lives are still working to meet that challenge.