The day Peggy Caserta took acid for the first time changed her life – and that of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood – forever.

“They told me it’d help me learn a book I was reading for class,” Caserta told the Bay Area Reporter in a recent interview. “I came off it and said ‘I don’t want to be a flight attendant anymore.’ I wanted to open a store. Walking down Haight Street – which wasn’t known at all at the time – I was looking for cheap rent and boy, did I find it: $87.50 a month.”

Caserta found that price at the storefront of 577 Ashbury Street, at the corner of Haight Street. The building is a city landmark and is on the National Register of Historic Places. The iconic intersection was named a national treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation in May 2019, and has a rich LGBTQ history stretching from Caserta’s days as the lover of Janis Joplin to the time it spent as the residence of Norm Larson – a prominent gay conservative who used it to host parties for the Log Cabin Republicans, home to the Grand Old Party’s LGBTQ members.

According to Mike Buhler, the president and CEO of San Francisco Heritage, the house has been singled out for preservation because of its significance to the countercultures that have defined much of San Francisco history, including the Summer of Love in mid-1967 in the Haight district.

“What happened in the 1960s is often derided as not ‘real’ or ‘significant’ history,” Buhler said. “Norm, when he was alive – in 2017, the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love – wrote his personal story of how he came to purchase the building. He would be delighted to have it more publicly available. There are several important aspects to the building’s history, as far as LGBT history.”

‘Front-row, center-seat’

Caserta, now 79, identifies as a lesbian, and said she set up the store at 577 Ashbury in 1965 “to appeal to gay women.”

“Women, especially gay women, were buying men’s jeans,” Caserta said. “So that was where we could hit both sexes – and we did.”

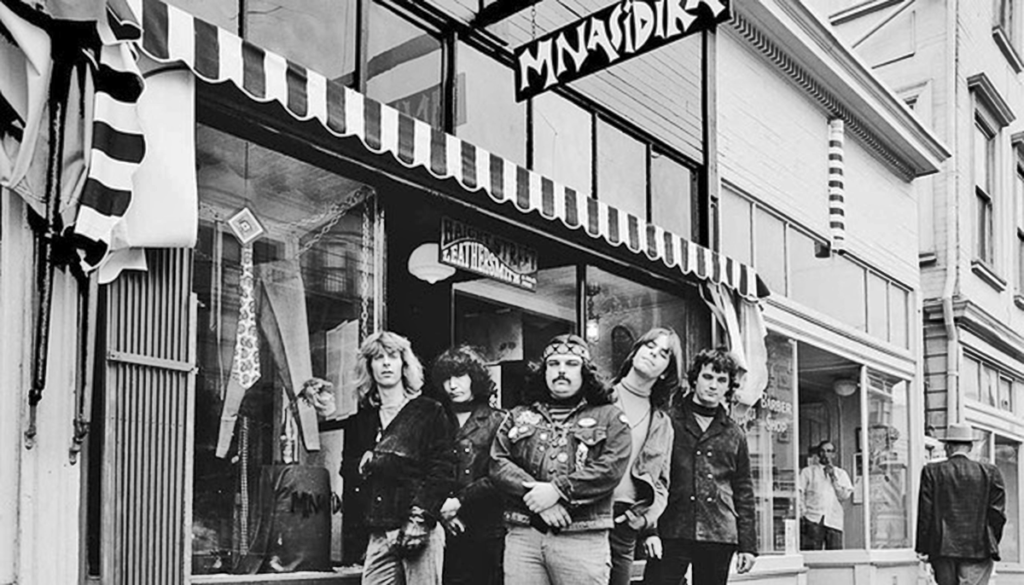

Caserta’s store, Mnasidika, shares a name with a character in the ancient Greek erotic lesbian poetry collection known as “The Songs of Bilitis,” from which the historic lesbian activist group the Daughters of Bilitis founded by the late Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin took its name.

As the Haight filled up with people from the world over coming to turn on, tune in, and drop out, Caserta’s store became popular as a place to buy denim, particularly bell-bottom jeans. Caserta’s mother made the jeans in the South and had them flown to San Francisco, where Caserta had them sold for $4.98.

Caserta eventually convinced Levi Strauss & Co. to make its first bell-bottom jeans, and she had an exclusive arrangement on selling them at Mnasidika for half a year.

A Levi’s spokesperson responded that Tracey Panek, Levi’s historian, wrote a blog post in late 2019 with more details on Caserta and her story.

Panek was unable to find any specific documentation of the monopoly (e.g. a contract or related papers with Caserta), however, her story checked out in terms of timing and the person she met, etc. Caserta and the man she met at Levi’s Valencia Street factory (believed to be salesman Joe Frank) worked out an exclusive arrangement for six months that Levi’s would only sell the style at her boutique. “Monopoly” suggests others may have tried to do it at the same time and couldn’t, but the company was not able to confirm this. It’s more that Levi’s didn’t produce and sell the style to anyone except Caserta for six months.

“For six months, I had the only Levi bell-bottoms in the world,” Caserta said. “I was successful beyond my wildest dreams. … The place exploded. The psychedelic revolution exploded literally in my doorway. All of the folks started moving in there and I had a front-row, center-seat.”

The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane stopped by – and so too did a singer-songwriter who moved in across the street from Caserta’s residence.

Caserta had first seen Janis Joplin in the neighborhood soon after she moved in.

“I had heard her sing at a dive on the waterfront and she knocked me off my chair,” Caserta said. “I thought ‘My God – that’s the girl across the street.’ She was unknown and was singing $5 a night for all the beer she could drink.”

Then, Joplin came into Mnasidika.

“She walked in one day and asked if she could put down 50 cents on a pair of Levi’s,” Caserta said. “The feminist popped out in me and I thought ‘if that were a guy singing like that, he’d have the $5 [to buy the jeans]’ so I thought I’d level the playing field.”

Caserta gave Joplin the jeans for 50 cents but the iconic singer worried Caserta would be fired.

“She came back and said ‘I know why you weren’t fired – this is your store,’” Caserta recalled.

The two became lovers. Joplin died October 4, 1970 of an accidental heroin overdose, the year Caserta said she closed shop and moved to Polk Street. (Caserta publicly disputes this, however; in spite of a coroner’s report, she insists Joplin tripped and fell.)

“It got dark and bad,” Caserta said. “You can’t have too much fun – you attract too much attention. People come in, and it’s not always fun-loving people.”

A different counterculture

The building at 577 Ashbury became kind of a flophouse for hippies before Larson bought it.

Larson, a graduate of Stanford University and Harvard Law School, taught English to military personnel in Iran, narrowly escaping the fall of the shah and the rise of the Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979. One year later, Larson bought the house and began a painstaking restoration process. In 1985 he moved in after evicting a tenant – leading protesters at the time to hang him in effigy.

Larson represented a different counterculture to the Summer of Love as a member of the Log Cabin Republicans.

As the B.A.R. reported on the occasion of the group’s 40th anniversary, the San Francisco chapter of Log Cabin began in 1977 as Concerned Republicans for Individual Rights to fight the Briggs initiative, a statewide ballot proposition that would have banned homosexuals and their supporters from teaching in public schools. (It was defeated in 1978.) Larson was a longtime member.

Chris Bowman, a gay man who is now semi-retired but ran in gay Republican circles years ago, was on the board of the San Francisco Log Cabin chapter from 1980 to 2005. He first met Larson in the 1970s.

“When he bought the place it was kind of a mess,” Bowman recalled. “He restored it and tried to be faithful to the original house. It was always a work in progress that was never fully finished. He had various artwork from the period of 1906-1910 and there were quite large windows overlooking Haight Street.”

Fred Schein, a gay man and a former president of both the San Francisco and Marin Log Cabin chapters, told the B.A.R. in great detail about his times at the house.

“I first met Norm eight or nine years ago,” Schein said. “Soon after that, I started going to his home at the northwest corner of Haight and Ashbury. That was where he lived. There was a business on the first floor and he was above it.”

Schein said that Larson threw parties and had gatherings at the home, which is a colonial revival built at the start of the 20th century.

“It’s fun to be in such an old place,” Schein said. “We had events there two to four times a year: chapter meetings, Christmas parties, guest speakers. It was a go-to place. If those people at the Summer of Love had known that same place was filled with gay Republicans it’d shock them.”

Schein said that Larson’s Christmas party was “one of the best in town.”

“We were supposedly rich Republicans and gay so of course it was,” Schein asserted, adding that the holiday menu often consisted of Chinese food.

“I’d sneak in Christmas cookies and stuff like that,” Schein said. “Norm was very hospitable and proud of his home. He had researched it and could talk about what happened in each room 80 years earlier. He’d rattle off names of old politicians. He knew them – we didn’t.”

Michael Gallardo, also a past president of the San Francisco chapter of Log Cabin, helped put together the parties.

“He agreed to host the party at his house if I did the organizing,” Gallardo, a gay man, said. “Norman was an excellent host. He had a huge collection of wine glasses. We always enjoyed having parties there. He footed the bill for the catering and was a generous contributor to Log Cabin on a yearly basis.”

Bowman agreed that Larson “loved showing off the place.”

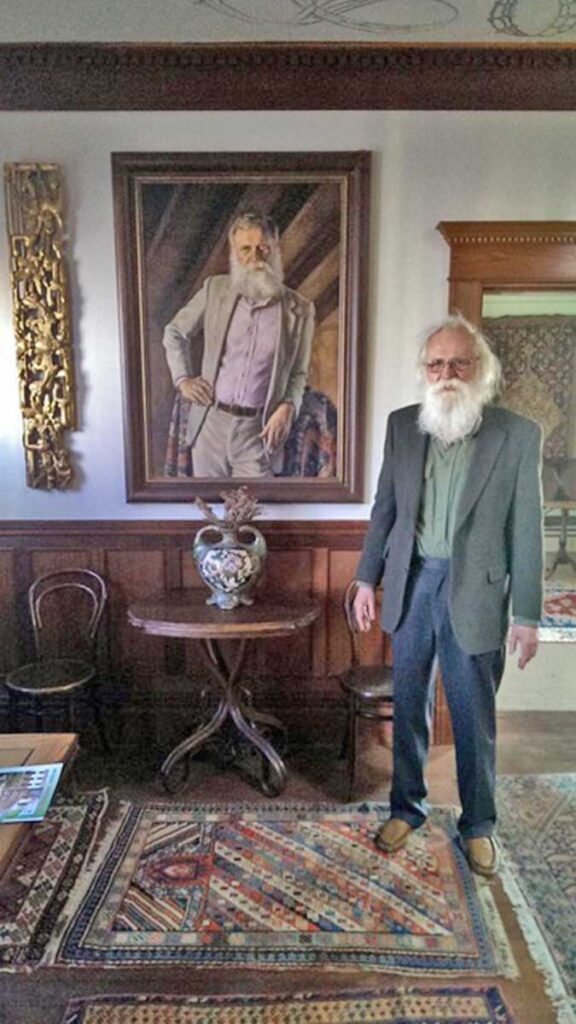

“When you entered the house, you entered a new world,” Schein recalled. “Quite dramatic, quite antique, heavy wood, a lot of redwood. We always had a lot of fun going up and down the staircase. Norm had a dramatic painting of himself that confronted you, with his grand, white hair and white beard looking like Colonel Sanders.”

One feature of the house Schein described was a heavy antique lead-lined icebox. Others included a mosaic Larson was putting back together, and large windows Schein said were evocative of Paris.

Schein said that Larson, a patron of the San Francisco Symphony, the San Francisco Opera, and baroque music, often invited the American Bach soloists to sing there.

“He got on every board he could get on,” Schein said of Larson, who, at the time of his death two years ago was called the “Duke of Haight Street.”

“I don’t know if I’ll meet anyone quite like him,” he added. “You never missed an opportunity to be there. He had a library in front of a cracked plaster wall with a whole cabinet of Iranian literature. I looked at it because I was fascinated by it.”

Upon his death, Larson bequeathed the building to San Francisco Heritage. (It is officially known as the Doolan-Larson Residence and Storefronts.) Buhler said that a team of experts is working with the national trust “to convert the building into a cultural destination.”

When asked how LGBTQ history would be featured when it becomes a destination – the San Francisco Chronicle ran a story about the house last year referring to Larson as an “eccentric bachelor” – Buhler affirmed that the LGBTQ story of the building is essential to its history.

“It’s difficult to say without an interpretive plan, but the building’s LGBTQ associations are an essential part of its story, from Peggy Caserta and her hip clothing boutique, Mnasidika, to its namesake, Norman Larson,” Buhler stated. “Sexual liberation is a central theme of the counterculture movement and San Francisco’s heritage, and will be prominently highlighted in any future cultural destination at the corner of Haight and Ashbury.”

Gallardo had fond memories of Larson and the house.

“It goes without saying that we miss Norm,” Gallardo said. “He was such a good man and we miss his company. I’d pick up a nibble or two at Gus’s Market and then stop at the house for baroque and great conversations. Norm was very well-liked, I’d say beloved.”

Schein, too, says he misses going to Larson’s home and said he knows if Larson threw a party in the era of COVID-19 he would have masks and a protocol at-the-ready.

“You felt special in that house,” Schein said.

John Ferrannini is an assistant editor at the Bay Area Reporter.