The number of LGBTQ-inclusive picture books has grown exponentially over the past decade, particularly in the last couple years. There are some topics and types of representation that are still lacking, however, so instead of reviewing existing books this week, I want to discuss some of those gaps.

First, we need more picture books that show LGBTQ characters and their families but whose main focus is not the LGBTQ angle. There is a slowly growing number of such titles, but far from enough. Sometimes a family with LGBTQ parents just goes to visit grandma; sometimes a transgender or nonbinary child has an intergalactic space adventure that has nothing to do with their gender identity.

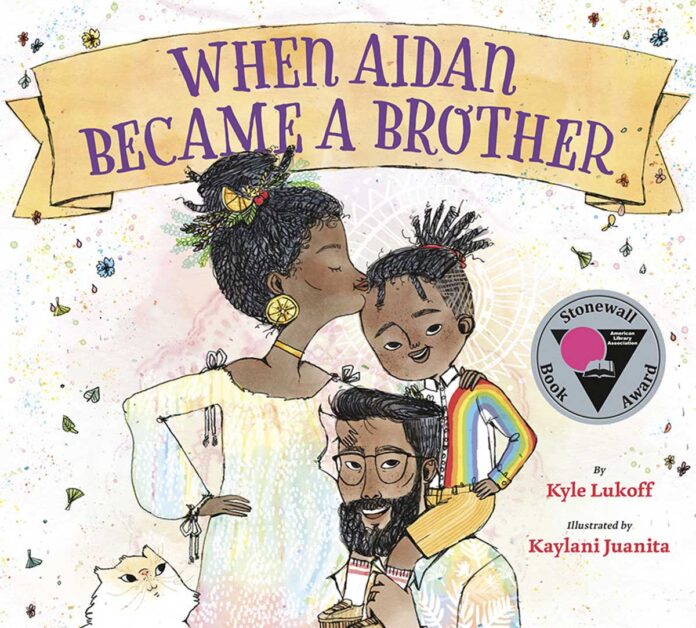

At the same time, such books don’t always have to completely ignore the characters’ LGBTQ identities either. Kyle Lukoff’s “When Aiden Became a Brother” and “Max on the Farm” are masterful examples of how to achieve this balance, bringing up the characters’ gender identities when relevant to a specific situation, but not focusing the stories on them.

We also need far more books centering the experiences of LGBTQ people of color and their families. Most LGBTQ-inclusive picture books of the past few years do indeed show people of color, but the vast majority of them involve making one parent a person of color (usually Black) and the other one White, or showing a classroom of children with various racial identities. It’s great to see this representation of multiracial families and schools, but we also need more books where the protagonist and their entire family are people of color. (There are a few, but not many.) Also sorely lacking are picture-book biographies of famous LGBTQ people of color.

I would like to see more LGBTQ-inclusive picture books that reflect the characters’ ethnic and/or religious heritage. There are none, to my knowledge, that show LGBTQ people or families celebrating Hanukkah, Easter, Kwanzaa, or Diwali, for example, and very few for other holidays. Such content would help show that LGBTQ people’s lives do indeed intersect with the many communities of which we are part and that LGBTQ identities and religious faith is not mutually exclusive.

Creating this content in authentic ways, however, also means engaging “own voices” creators who share identities with their subjects. Smaller independent publishers such as Flamingo Rampant, Reflection Press, and My Family Products are leading the way here; larger publishers would do well to follow their examples.

There are also no picture books that show clearly bisexual parents. I think there are ways for writers to make a parent’s bisexuality visible and still avoid centering the book on it as an “issue.” A parent could mention or encounter a person they dated in the past, of a different gender than their current spouse/partner, or a single parent could convey an interest in marrying someone of any gender, for example.

We also need more picture books that feature kids with transgender or nonbinary parents, in addition to the growing number with trans and gender creative kids. Gayle Pitman’s recent “My Maddy” stars a child speaking lovingly about her nonbinary parent, and the upcoming “She’s My Dad!” by Sarah Savage will help fill the gap, but there are many more stories to be told.

Despite the need for more “non-issue” books, children can still benefit from thoughtfully written titles that do address some of the specific situations that kids of LGBTQ parents and LGBTQ children may encounter. There are many such topics that have not yet been covered extensively in picture books, such as a parent’s gender transition or how queer families form, especially from the perspective of a child watching their LGBTQ parents bring a new sibling into the home, whether through assisted reproduction, fostering/adoption, or other means. A few mostly self-published books exist, but given the variety of queer experiences, there is room for many more.

Children could also benefit from picture books about other potentially puzzling or difficult family moments — like when parents are divorcing, dating someone new, or remarrying — told through the lenses of LGBTQ families. There are a couple of self-published works that cover these topics (and the very first LGBTQ-inclusive picture book in English, Jane Severance’s 1979 “When Megan Went Away,” was about parental separation), but again, there are many possible situations and stories that have not yet been covered.

It’s worth noting that many LGBTQ-inclusive kids’ books have been self-published and often stem from the authors’ own families. They deserve our praise for taking the time to write themselves into these stories. Yet self-published books can be a mixed lot, quality-wise, and often don’t get the marketing required to become known to the readers seeking them.

We should therefore support independent authors, not only by purchasing their books but also by finding ways to help them hone their craft (e.g., constructive but kind feedback in online reviews) and to share it widely when we enjoy it. Highlights Foundation last year held a workshop on writing LGBTQ-inclusive picture books, with instruction from published luminaries, which was another step in the right direction.

At the same time, we should push larger publishers to seek out diverse talent across many dimensions, to bring out additional LGBTQ-inclusive picture books on the topics above, and to reach out to LGBTQ organizations, journalists, and other writers to help spread the word. Children of LGBTQ parents and LGBTQ children will benefit, and so will their peers. Everyone enjoys an intergalactic space adventure now and then.

Dana Rudolph is the founder and publisher of Mombian (mombian.com), a GLAAD Media Award-winning blog and resource directory for LGBTQ parents.