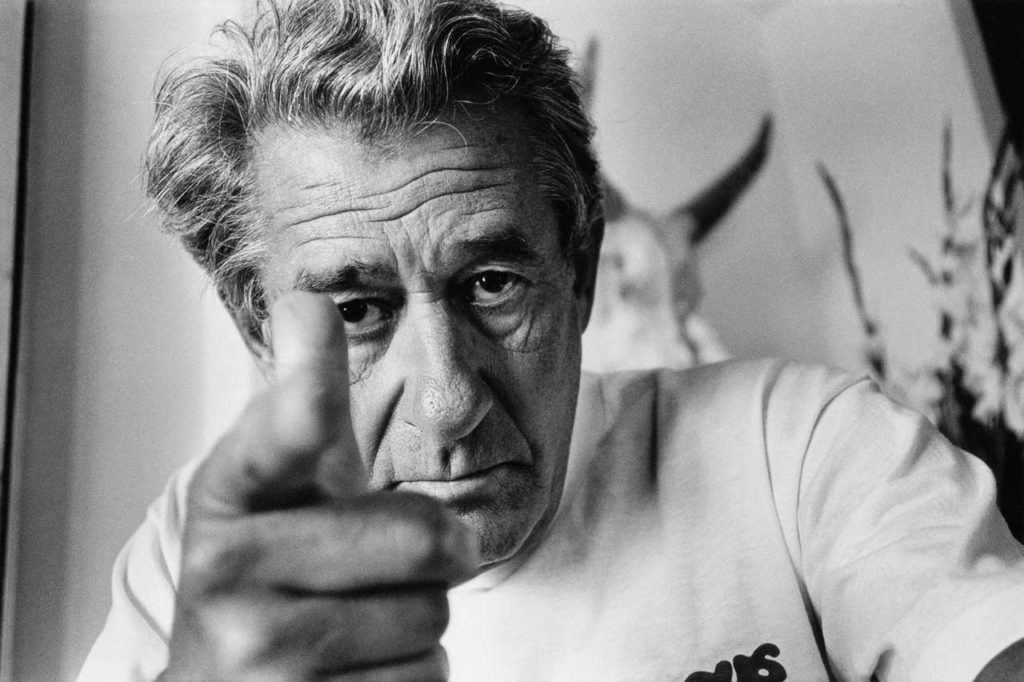

The stylish documentary “Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful,” opening July 24 in virtual cinemas, chronicles the work and life of the famed fashion photographer who died in 2004. Director Gero von Boehm assembles archival footage, photographs, and interviews with several women who modeled for Newton, creating a celebratory portrait of a man who liked to provoke.

The first part of the film showcases Newton’s work — he abhors the word “art” (as well as the phrase “good taste”) — to illustrate his distinctive style. Newton’s photographs feature dominant, often-naked women in arresting poses that portray “stories” of manipulations and control.

Queer icon Grace Jones describes how he lit a shot of her, naked and holding a knife, with strategically placed shadows, and commends Newton for being erotic, not vulgar. She also admits, “He’s a little perverse…but so am I!”

Jones is infectious in her interviews, even when she laughingly recounts a story that Newton thought her breasts were too small. But Jones is also subject of one of the controversies in the photographer’s career. A shot Newton made for a magazine cover, featuring Jones naked and chained at the ankle, caused a scandal; it was deemed sexist and racist. Jones claims she was “acting,” but viewers may have more woke thoughts.

The debate over the photographer’s work is very stimulating and a highlight of the doc. One model, posed like a Barbie doll in a photo, suggests Newton is commenting on society being sexist. Isabella Rossellini explains that women in Newton’s work are portrayed as sexual objects. Photos of a woman naked on all fours, or another with a saddle on her back, or a nude woman lying in the mouth of an alligator make this case. The question is raised: are they being exploited?

Thankfully, bisexual writer Susan Sontag cuts Newton down to size on a French TV talk show. When Helmut says he “loves women,” Sontag retorts, “A lot of misogynist men say that, but I don’t think it’s the truth.” She also claims his comment is not unlike “a master saying he loves his slave.”

“Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful” could have used more humbling moments like this. Instead, von Boehm goes in the other direction, with interviews that champion him and his work. Actress Charlotte Rampling, who modeled nude for Newton, defends the photographer. She states that the vision he has is not his life, adding the importance of separating the art from the artist. It’s a fair point, echoed by Claudia Schiffer who comments about the different “characters” she got to play for Newton’s lens including a typical German girl and a more sexually provocative female.

Crocodile, Wuppertal, 1983 Photo courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

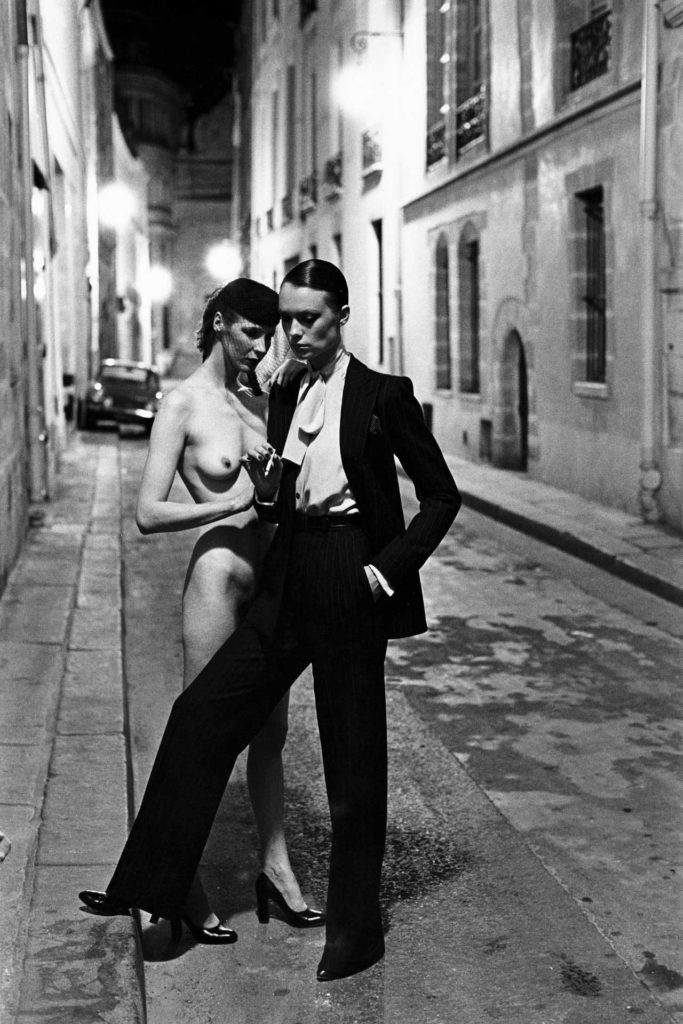

Rue Aubriot, Paris, 1975 Photo courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

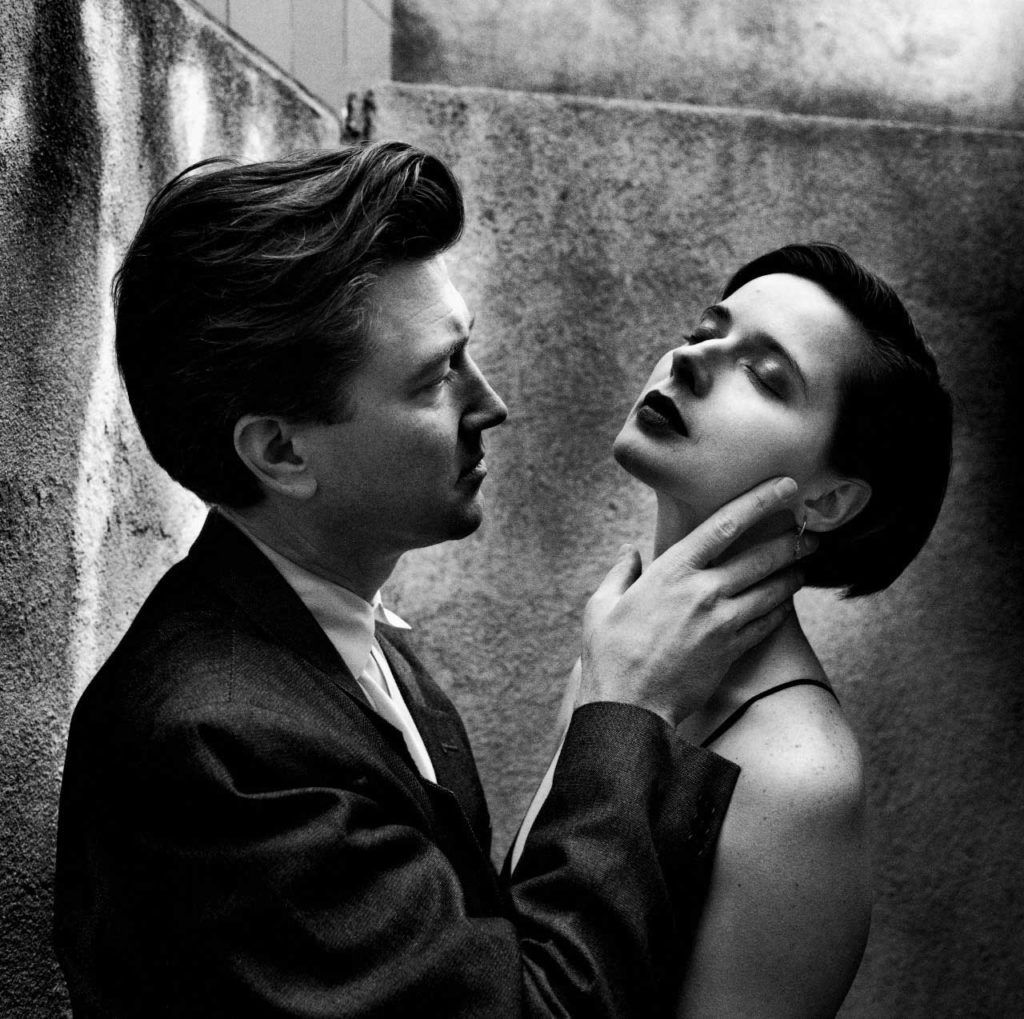

David Lynch and Isabelle Rossellini, Los Angeles, 1988 Photo courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

Arena, Miami, 1978 Photo courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

Von Boehm lets many of Newton’s images, which address power dynamics, speak for themselves. The German actress Hanna Schygulla talks about how Newton appreciated a pose where she displayed her underarm hair. The photo irked folks who wanted a more polished image. One photo spread he did for “Vogue” was considered an insult to disabled women. Another shot he took featuring a woman wearing a fancy Bulgari ring and bracelet and the cavity of chicken wasn’t appreciated by the jeweler.

Newton explains that, “It takes great pains to get a good photo.” He is not wrong. However, while provocation is fine, when Newton is seen on a shoot telling a female model to spread her hand wide on the crotch of the male she is embracing — and hoping the guy will get aroused — it may be going too far.

If Newton is not entirely likeable as an artist, despite the parade of effusive interviewees, the film’s second act, which addresses his family and childhood, makes him more sympathetic. It shows how Newton was 13 when Hitler came to power. As a teenager, he apprenticed for Yva, the first fashion photographer. (She later died in the concentration camps). But he left Germany, ending up in Singapore, before being sent to Australia, where he met his wife, June. These details are fascinating, and von Boehm could have told Newton’s personal story in more depth. Instead, he focuses on the work, with a comparison of Newton’s photographs of strong women to how Leni Riefenstahl filmed strong men.

Another underdeveloped aspect of the film involves an exhibition of Newton and his wife’s work that prompts some doubts after out gay designer Karl Lagerfeld sends Newton a letter questioning the show.

Newton is shown to use his camera as a protective device against embarrassment and maintain a distance from things such as June’s stay in a hospital. This is a revealing, if unsurprising insight, but it indicates how Von Boehm’s documentary captures its cagey subject. Newton claims to be a “naughty boy,” who liked breasts, faces, and legs. He was not interested in souls. And that extends to baring his own.