A few weeks ago, Senator Lindsay Graham (R-SC) made headlines when Sean Harding, a gay porn actor, indirectly suggested on Twitter that Graham had hired numerous gay sex workers. “Every sex worker I know has been hired by this man,” the tweet read, “wondering if enough of us spoke out if that could get him out of office?” The phrase “Lady G,” a nickname used among the escorts Graham allegedly hired, quickly became a trending topic. The event rekindled a debate that has happened for eons in the LGBTQ community. Should people be forced out of the closet against their wishes?

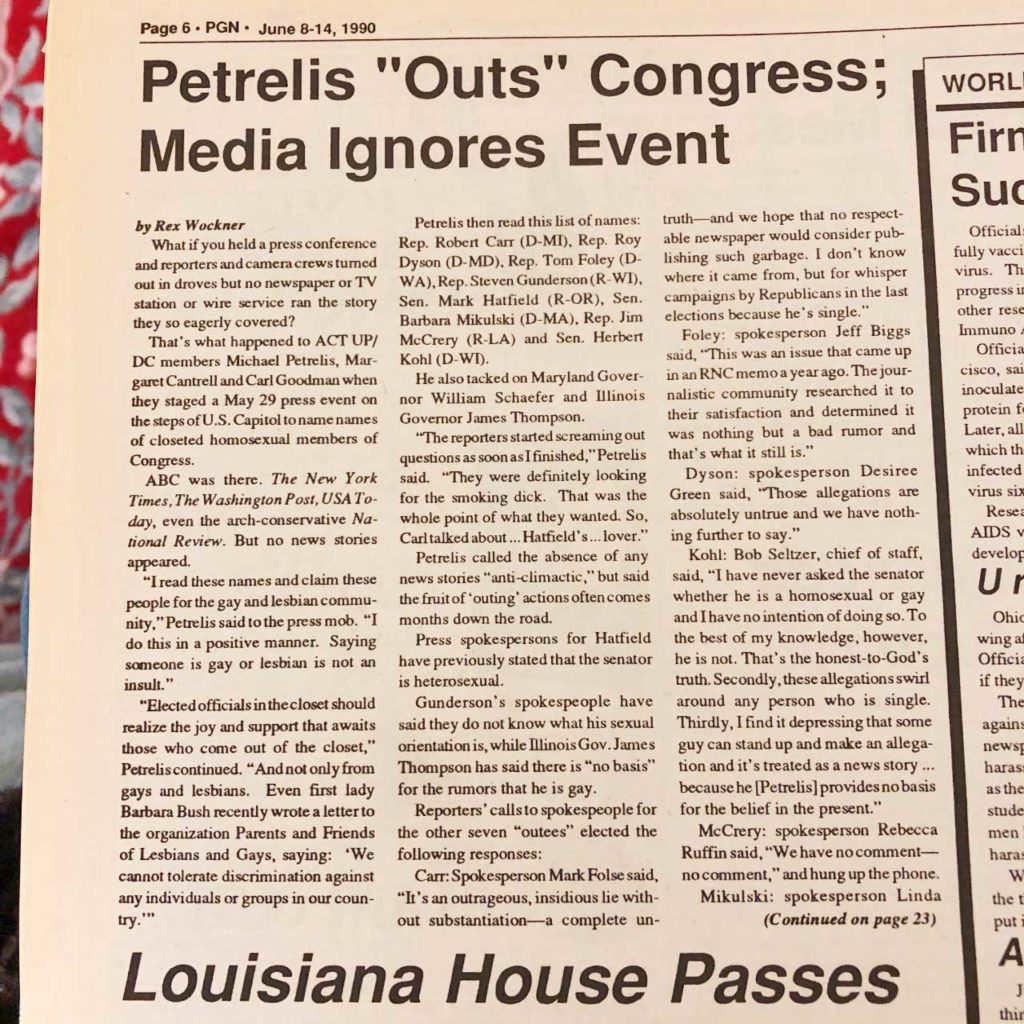

Outing, specifically among politicians, has happened for decades. In May of 1990, PGN covered a press conference held by three members of ACT UP in Washington, DC who revealed the names of eight members of Congress and two governors who were thought to be gay or lesbian. The list included Republicans, Democrats, supporters of gay rights and opponents. Some of the politicians came out later in life, some remained in the closet their whole lives, and some held firm to their heterosexuality. One of the men named at the press conference, Rep. Steven Gunderson (R-WI), was outed by a fellow Republican on the floor of Congress a few years later.

The press conference drew controversy within the LGBTQ community. Organizers had initially sought the help of the Human Rights Campaign and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force to help compose the list of closeted politicians, but both groups refused. A spokesperson for the NGLTF said “This organization does not endorse outing,” while the HRC more pointedly stated, “Do they want to create a climate where it is chilling to be gay? Are we using homosexuality as a weapon?” The event was controversial enough—due in part to a lack of evidence for some of the politicians who were outed—that ACT UP DC did not fully support the press conference.

Then and now, there are widely differing points of view on the morality and the effectiveness of outing. Would it cause anti-gay politicians to change their stances, or make it easier for a challenger to unseat them? Would it inspire more people to come out? Or would it cause a backlash? Would those politicians dig deeper into their stances? Would the action come across as solely an attempt to ruin a person’s reputation?

Historically, the outcome of outing has been as varied as the opinions about it. Gunderson continued to be a supporter of gay rights and was the only Republican Congressperson to vote against the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996. Rep. Edward Schrock (R-VA) chose not to seek reelection after being outed. Schrock had previously voted against LGBTQ rights. New Jersey Governor Jim McGreevey chose to come out before allegations surrounding him were released, and he has been an ardent supporter of the queer community. But often times, people who were outed simply chose to ignore or deny the allegations and resume their lives.

The recent headlines involving “Lady G” have spurred the same debate over whether outing is always right or always wrong or whether it’s a valid tactic on a case-by-case basis, especially for politicians whose voting records seek to harm queer people.

Former Congressman Barney Frank (D-MA) threatened to out Republican colleagues in the late ‘80s when the Republican National Committee released a memo implying that Speaker of the House Thomas Foley (D-WA) was gay. In a 2015 interview with Washingtonian Magazine, Frank said he had threatened to out people twice “in cases where the Republicans were using ‘gay’ as a weapon.’”

In the 2004 Presidential election, Republicans did use ‘gay’ as a weapon, though not in the way Frank envisioned. 11 states decided to put a question on the ballot regarding the Federal Marriage Amendment (limiting marriage to heterosexual couples). All of those states saw a majority vote in favor of the Amendment, including in swing states such as Ohio, where conservative Christian voter turnout was high. That year, Republican President George W. Bush won re-election over Democrat John Kerry, and some exit poll data suggests that the Amendment helped drive turnout among Bush voters.

That same year, Mike Rodgers, perhaps the most well known political “outer,” started BlogActive, a site that revealed the names of anti-gay politicians who were known to have same-sex encounters. For seven years, Rodgers outed a whole host of Republicans including high profile members like Schrock, RNC staffer Dan Gurley, and Bush’s campaign manager Ken Mehlman. Some of them were replaced with less anti-gay politicians, and several of them ultimately became gay rights supporters

In a 2015 feature in Politico, Rodgers explained his idea behind outing was to point out the hypocrisy of anti-gay politicians who wanted regulate the private lives of LGBTQ Americans.

“The media have always written stories,” Rodgers said, “about straight politicians who take hypocritical positions on different issues—a secure-our-borders conservative who employs undocumented immigrants or a politician who argues against a woman’s right to choose while secretly arranging for an abortion for his mistress. So why not do the same for gay politicians?”

No matter how one views outing, the idea that hypocrisy should be called out is an important one. It mattered in 1990, in 2004, and it matters today. Everyone should be judged by the same standards. Nobody is above the law, including, and especially, those who create it.