Content warning: This article features accounts of police brutality and first-hand accounts of sexual assault.

The Stonewall uprising is America’s premier example of police brutality against LGBT people. Years of harassment and attacks on queer and trans people culminated in what was called the Days of Rage in Greenwich Village in June 1969. Ever since, June has been celebrated as Pride Month.

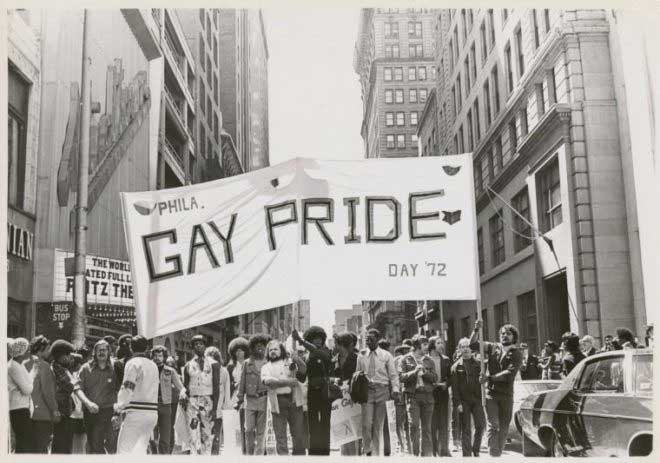

But police harassment and brutality against LGBT people was endemic across the U.S. In Philadelphia in the 1960s, Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo had a policy of anti-gay harassment. He rounded up gay people late at night from the clubs and streets of the Gayborhood and along the Merry-Go-Round in Rittenhouse Square. That legacy of abuse continued throughout his tenure as mayor, from 1972 to 1980 and beyond.

On June 3, as a result of days of protests against police brutality against Black people throughout Philadelphia, the 2,000 pound, 10-foot tall bronze statue of the former mayor was removed from Paine Plaza across from City Hall during the night by city workers under the aegis of Mayor Jim Kenney. The statue, erected in 1998, had long been contentious among Black and LGBTQ Philadelphians due to Rizzo’s documented history of racism, homophobia and transphobia.

“The Frank Rizzo statue represented bigotry, hatred, and oppression for too many people, for too long. It is finally gone,” Mayor Kenney tweeted the morning after the statue was removed.

On June 7, the three-story mural of Rizzo in the Italian Market was painted over. The Mural Arts Program issued a statement, “We know that the removal of this mural does not erase painful memories and are deeply apologetic for the amount of grief it has caused… We agree it is time to replace this long-standing piece of art to begin to heal the Black community, the LGBTQ community and many others.”

As a reporter, activist and archivist of Philadelphia LGBTQ history, Tommi Avicolli Mecca experienced the anti-gay harassment of the Rizzo years first-hand.

“I remember the constant violence and threats of violence from ‘Philly’s Finest’ after I came out,” Avicolli Mecca said. “I was in a raid at the old Allegro [a gay bar at Broad and Spruce Streets during the 1960s and 1970s] and escaped being arrested only because the guy in the kitchen let me out through the yard. I was underage. The cops had not gotten their payoff.”

Jackie Marcus, a butch lesbian who frequented the clubs in the 1960s and 1970s, said raids on the bars were common. “The cops would take you to the back of the bar and try and force a blow job by threatening to contact your job, ” she said. “It was all about humiliating the butches — they wanted us to literally kneel to them. It was disgusting. It was brutal because they’d hold your head down. A lot of us who had to choose [between their job and sexual assault] will never forget it. Now we know that stuff was criminal. But then, we were just young and scared and did what we were told.”

Roberta L. Hacker was a young social worker and lesbian activist in the 1970s when she became the star witness in the first federal police brutality trial in Philadelphia. A Black man, William Cradle, was stopped by police for allegedly running a stop sign in Society Hill. Hacker, her then partner and a friend were driving home to their apartment at 16th and Spruce Streets when they witnessed several police officers drag Cradle from his car and beat him with nightsticks.

Three police officers were charged in the attack.

The women reported the incident to police, the U.S. attorney’s office, the Philadelphia Inquirer and the FBI. The investigation and subsequent trial was a national news story for months. The women were harassed by police, who would come to their apartment late at night, claiming there had been disturbance calls. Hacker was stopped repeatedly while driving and her partner sexually harassed by police.

The trial itself lasted for over a week and then-Mayor Rizzo spoke on the local news about the women, naming them, outing them and calling them liars.

“It was very disturbing and frightening,” said Hacker. “The threats were constant and ongoing. It was only a few years past Stonewall and there were not a lot of out professionals at that time. It was clear the police wanted to threaten me into silence and when they couldn’t, attempt to punish me by threatening my job by outing me.”

Hacker, who has been executive director of several social service agencies over the past 40 years, has dealt with police in myriad other contexts since that trial. But she says the experience defined her perspective. “I have worked with police as allies in aiding domestic violence victims,” she said. “But I also know that police can be abusers, and there is a blue line of silence over that.”

And like Avicolli Mecca and Marcus, Hacker experienced harassment in the clubs. “What I learned from the Cradle case was that abuse of power harms our entire society. And for marginalized groups like women, people of color, LGBTQ, that power can literally mean the difference between life and death.”

Avicolli Mecca puts the Rizzo years and the long reach of his legacy in perspective. “I saw cops shoving members of Dyketactics down the steps of City Hall after a peaceful protest that day in 1975 the gay rights bill died in City Council,” he said. “I remember AIDS activists being beaten on Broad Street during a peaceful protest outside a hotel where the president was speaking.”

Avicolli Mecca continued, “I remember the cops going after gay men cruising in Judy Garland Park and being threatened with arrest because some of us stood there handing out flyers warning men of the danger. Luckily, we had a gay attorney with us who reminded the cops of our right to flyer. I remember a dozen trans women of color being murdered and the police not wanting to do anything. I remember that even after Rizzo left City Hall, his ‘spacco il capo’ — split their heads — style of policing continued in the department for many years. Rizzo was never a friend to our community.”

The Rizzo years of brutality may be over, but the tensions remain. And right now, this country is fighting to end police brutality against Black people, against Black queer and trans people, against society.