For the most part, PGN has not changed much in 44 years. Front page news stories, arts and entertainment spreads, editorials, special features. Week after week, we provide readers with a consistent lineup of news and arts information, and it’s been that way since 1976. One section of PGN, though, has changed dramatically over time: the personals section. Yes, the one where people wrote about themselves in the hopes of finding romantic companionship or, for the most serious, love. In a way, print personals were much more egalitarian than any dating app or web site. There were hardly any photos (due to cost), so people had to rely on words alone. If someone liked what they read, they’d respond by writing a letter or giving a call. It would take time to develop, as is the case with many relationships.

In PGN’s first issue in January 1976, personals ads appeared in section “X,” a pullout section that included classified ads for things like books, photo magazines, marijuana seeds, sex toys, cassette tapes, and LGBT resource packets. In addition to mail order items, advertisers in the section included bookstores, saunas, and cinemas.

The personals in 1976, for the most part, were short and succinct. Most people wrote one or two lines about themselves, their age, hobbies and the type of person they were looking for. Most provided their addresses. The ads ranged from “lonely housewife looking for companionship,” to “gay sci-fi nut wants to correspond with other sci-fi fans” to “good looking bodybuilder wants well-hung studs for action.” There are ads about missed connections, the “I wish I’d gotten your number” sort. There’s even an ad from a teacher seeking to collect stamps for their school’s stamp club. It all seems very normal and very tame by today’s standards. The most common type of personal ad — men seeking men — numbered 45 in total.

Flash forward three years to 1979, the 10-year anniversary of Stonewall. The most striking feature of the ’79 classifieds is the addition of two full pages of community resources. Counseling services, radio shows, religious groups, nonprofits, medical clinics, support groups, coffeehouses and hobby clubs. And it wasn’t just limited to Philadelphia. Ads for groups, services, and people ranged from cities like Atlanta to Indianapolis. It’s unsurprising considering the number of LGBT publications was still small in the late ’70s. But, considering the dearth of options three years earlier, one can see plainly the community evolve and expand in real-time.

The same can be said for the personals section, whose numbers shot up to 175 ads for men seeking men. That’s an increase of nearly 200% in three years. In addition to featuring photos, the “profiles” written were lengthier. Most were eight or nine lines rather than two or three. People were more willing to reveal themselves and get specific about their hobbies, locations and desires. One person even wrote a poem about his dream guy. It’s worth mentioning that, like Grindr today, some of the ads were offensive. The most common derogatory slur “no fats or fems,” appeared in seven ads (4% of the total). But for the most part, the language used was harmless.

A decade later, in 1989, the community was in the full throes of the AIDS crisis. This was reflected not only in the news articles and entertainment content of the paper but also the personals. Some ads included phrases such as “safe only,” “HIV-neg,” and “no sex.” A term used heavily was “no drugs,” perhaps alluding to the idea that heavy drug users were more likely to be HIV-positive. PGN also put notices throughout the pages that reminded people about safe sex and HIV testing and support resources.

But, amidst all the uncertainty, the classifieds in 1989 still continued to grow in page length and number of ads. There were four more full pages of classifieds than in 1979. Most noticeably were greater numbers of international groups, gay men from France, Germany and Italy, and the wider variety of clubs and organizations including sports, opera, lawyers, runners, parenting groups. Another aspect that increased was the number of hotlines, escort services and ads for gay businesses. There had been a steady increase in every aspect of gay life from the ’70s to the ’80s, and that is plain to see when comparing the classifieds.

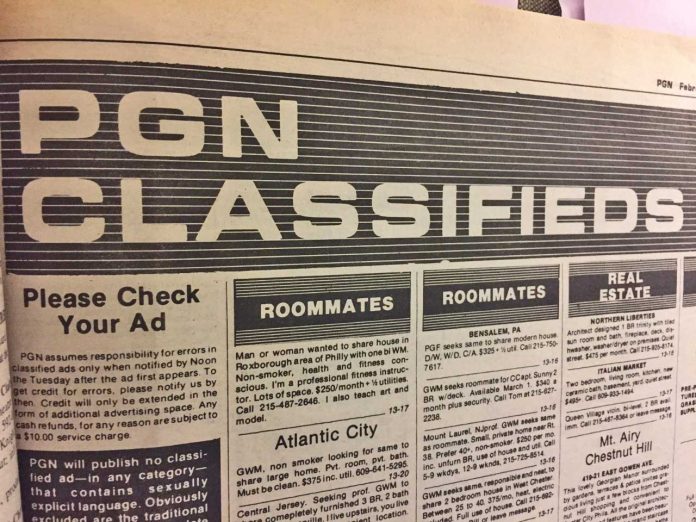

One noticeable change in the ’80s was that the classified and personal sections became a permanent part of the paper. They weren’t in a separate pullout called section X. They weren’t designed to be hidden. They were mixed right in with everything else. Another change was the shift in gender: 1989 saw many more ads for women seeking women than 1979, and there were ads for support groups for “spouses of gay men.” It speaks to an even greater acceptance, to the fact that the community didn’t only include and impact the men.

1999 was the year of the phone personal. PGN had shifted from traditional written classifieds, where interested parties could write to an address or contact PGN, to phone classifieds, where people called into specific voice mailboxes and could provide their information there. There were six full pages of phone ads, but because the ads themselves were smaller and more uniform, the total was almost as many as 1989. Another noticeable addition was the explosion of escort advertisements. While escort ads were common in 1979 and 89, 1999 was the first time they took up more page space than the personals ads themselves. The changes in layout are reminiscent of the old AOL home page: square lines, boxy icons, bold text. Perhaps it was a signal for what was to come: the shift from print to online.

In 2009, as expected, the personals section of PGN was virtually dead. The number of ads dwindled from several hundred in the 1970s to six — yes, six — in the 2000s. The ads for escorts, sex shops and massage workers were down. Even the listings for community groups and resources were slim. The internet and its immediacy had fully co-opted the space for classifieds, and people never looked back. There was simply no saving the printed personal.

A few weeks ago, I checked the back of PGN to see if anybody was still placing personals ads. I smiled when I found three of them, in small print, two to three lines each. That’s three people still holding out the hope that someone will see their words and phone them up. And who knows, perhaps when we’re all allowed to go outside again, those three ads will catch someone’s eye.

From 6 pages in 1976 to 12 pages in 1989 to one quarter page in 2020, the rise and fall of PGN’s and, to be frank, all print classifieds, is a tale of shifting technologies, a lesson in capitalizing on the cultural moment. It’s too convenient to search and make contact with someone instantly than flip through a newspaper and have to send a letter. As inauthentic and toxic as website and smartphone personals can be, their quickness and simplicity is what will keep them in use. But they’ll never have the charm that print did, and for that, PGN’s personals are worth remembering.