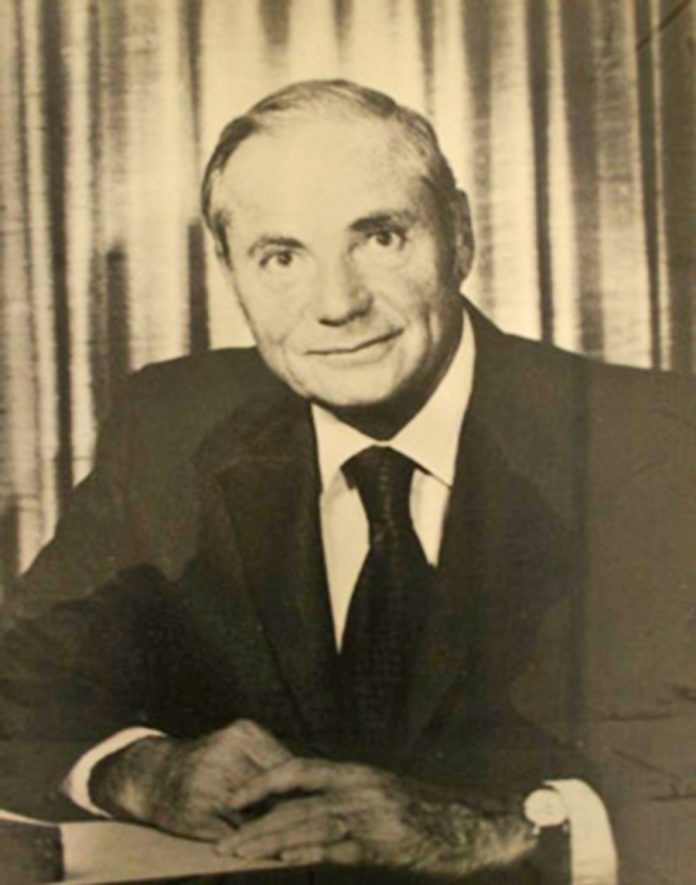

In March 1976, Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp, an ardent supporter of gay rights who used his political power to help the community, created the Council for Sexual Minorities. The first of its kind in the country, the Council’s goals were to “clearly define the problems of sexual minorities throughout the Commonwealth and to recommend ways in which discrimination against sexual minorities can be ended.” In addition to suggesting new legislation to help LGBT people, the 32-member Council was also tasked with studying and reporting on existing legislation that affected the community.

The Council’s name came from Shapp himself. The governor insisted that the word “minority” be included because he wanted the public to understand that LGBT people were a minority and deserved all the rights afforded to any other minority. He filled the Council with a variety of state officials and nongovernment workers, including lawyers, social workers, union heads, a congressperson and longtime LGBT activists including Barbara Gittings, PGN Publisher Mark Segal, and former PGN writer Harry Langhorne. Tony Silvestre, who served on the Council’s precursor, the Gay Rights Task Force, was named chairman.

On March 6, 1976, PGN published the first article about the Council, titled: “History Made As Pennsylvania Council for Sexual Minorities Established”

The Council was the first government-appointed, government-supported commission whose sole purpose to study and improve the lives of LGBT people. For the first time in history, the government, in a small but meaningful way, decided to put gay people first. The LGBT members were paired up with the government employees and tasked to work, step-by-step, on making each state department more equitable. And although the legislature at the time was not open to gay rights laws, the Council and the governor were able to create change by using executive orders.

“What it really showed more than anything else,” Segal said, “was the ability to create a dialogue between the LGBT community and statewide government. It had a major impact not just on governance, but on electability in this state.”

Under the Council’s guidance, the state police began accepting homosexual recruits and state insurance providers were no longer allowed to deny policies to LGBT people. Shapp also issued an executive order of his own that banned antigay discrimination in state agencies. Nearly as soon as it was introduced, the Democratic-led state senate introduced legislation to revoke the order, along with several homophobic laws including one that forbade gay people from any employment working with children. Shapp vetoed the bill, as he did with all other homophobic legislation. The pass-and-veto practice became so common and so anticlimactic that most state media stopped reporting on anti-gay bills altogether.

When Shapp left office in 1980, the Council, although technically still in existence, began to diminish. It was officially disbanded in 1988 when new governor Bob Casey Sr. failed to reappoint any of its members.

However, 42 years later, a new Council, same in spirit but different in name, was created by Governor Tom Wolf. The goal of the Pennsylvania Commission on LGBTQ Affairs is much the same as Gov. Shapp’s Council, to find ways — through laws or other means — to make queer people’s lives better. One of the members of the new commission, Jason Landau Goodman, along with the Pennsylvania Youth Congress, wrote the proposal that ultimately led to the new commission being created. Throughout the process, they drew inspiration and instruction from the original 1976 Council.

“It was tremendously inspiring to study the work of advocacy trailblazers in the 1970s,” Goodman said. “They were bold in their vision and accomplished in their mission. I am especially grateful that the Council was intentional about serious rural representation.”

The current commission’s task list is long. Among the issues under constant discussion are improving rural LGBTQ healthcare access, ensuring safe communities for trans women of color and providing for workforce development opportunities for LGBTQ youth. In addition, the anti-gay Republican-controlled legislature means, just as it meant the 1970s, that the commission and the governor are limited mostly to creating change through executive orders. However, despite the challenges, Goodman remains hopeful and excited about the Commission’s work.

“I’m proud that our Governor’s office has invested capacity into being more responsive to the needs of LGBTQ Pennsylvanians. There is great promise in the Pennsylvania Commission on LGBTQ Affairs, and I look forward to our work ahead to realize the vision that our state government can be attentive and responsive to the urgent needs of vulnerable LGBTQ Pennsylvanians.”