Out actress Kristin Stewart plays the title character in “Seberg,” an engrossing character study opening at area theaters on Feb. 28. The film, directed by Benedict Andrews, and written by Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse, traces the actress-turned-activist Seberg’s life starting in May 1968. The story focuses on a specific period of her life — when she was under surveillance by the FBI for her association with the Black Panther Party. This approach allows viewers to understand and appreciate the difficulties the actress faced under a specific kind of scrutiny. While there are references to her best-known films, “Joan of Arc” (and director Otto Preminger’s cruel treatment of her) and “Breathless,” “Seberg” is hardly a hagiography.

The film opens in Paris, as Jean leaves her husband, Romain (Yvan Attal), and their young son, Diego (Gabriel Sky), to return to Los Angeles for work. She is accompanied by her manager, Walt (Stephen Root), who wants Jean to get the female lead in the Western musical, “Paint Your Wagon.”

On the flight, Jean encounters Hakim Jamal (Anthony Mackie), a Black Panther, and connects with him after deplaning — striking a pose with the Black Panthers on the tarmac for the media. Walt is dismayed, but Jean is not discouraged. Later that night, she visits Hakim in Compton, and they talk about social justice politics and have sex.

As this late-night meeting takes place, FBI agent Jack Solomon (Jack O’Connell), is in a van, parked outside, recording it all. Soon, the bureau sees Jean, a celebrity, as being “dangerous.” Jack and his colleague Carl (Vince Vaughn) are given full authorization by their boss, Frank Ellroy (Colm Meaney), to tail Jean, bug her house and prove that her relationship with Hakim and her association with and support of the Black Panthers pose a threat to America. The FBI wants to “cause her embarrassment and cheapen her image in the eyes of the public.”

“Seberg” crackles as it shows how Jean operates blithely unaware of all the attention she is drawing to herself. She writes checks to help fund the Panthers and opens her home for a party that is attended by Bobby Seale (Grantham Coleman).

Curiously, Andrews parallels Jean’s story with Jack’s to create a thematic bond between the characters. He shows how this surveillance assignment takes a toll on both of their lives, which is perhaps a misstep because it shifts the focus away from Jean.

While several smear campaigns Carl hatches victimize jean — the most nefarious involves a pregnancy rumor — Jack becomes more sympathetic to his target. It is as if he is experiencing Stockholm Syndrome in reverse. In a critical episode in a New York hotel room, Jean realizes she is under surveillance and that she is not paranoid. Moreover, Jack is prompted to call Jean, anonymously, and warn her. This, however, inspires her to double down on her actions.

Andrews’ film starts to get a little contrived here. The scene in the hotel room is manipulative. And Jean’s descent into madness, which affected her work, personal life and emotional state (she attempted suicide), feels rushed. Stewart conveys the stress and strain and Jean’s self-destructive behavior, but “Seberg” veers into melodrama here, losing the cool tone of the film’s stronger first half. As Jean, full of despair, walks, drink in hand, into her swimming pool, it feels cheap and obvious. In contrast, Jack’s morals are strengthened after he witnesses an ugly (and heavy-handed) moment between Carl and his daughter Jenny (Jade Pettyjohn), at a dinner table. Thankfully, the film recovers from these lapses with a quietly powerful ending.

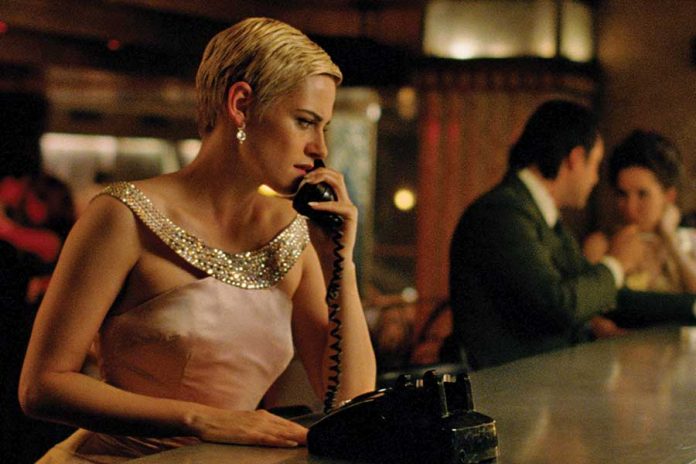

“Seberg” benefits from Stewart’s assured performance. Stewart is less interested in mimicking the actress than capturing her essence. And she is magnetic sporting Seberg’s iconic, short pixie haircut and the fabulous period costumes. (The 1960s production design is also notable). Stewart is best in a scene where she absorbs an intense exchange with Dorothy Jamal (Zazie Beetz) — who learned that Jean slept with her husband. And the way she handles a difficult press conference, where she must suppress her anger while trying to gain public sympathy, is impressive.

As Jack, O’Connell gives a largely internal performance, which shows how he, like Jean, must control his emotions. This makes the few scenes of Jack displaying his rage forceful.

Andrews’ film nobly wants to address the politics Jean championed, but what “Seberg” does best is validate its subject’s story, which is both tragic and a travesty. This biopic may not have the same impact as gay filmmaker Mark Rappaport’s fantastic 1995 documentary, “From the Journals of Jean Seberg,” but it should generate some interest in the actress’ brief life and career.