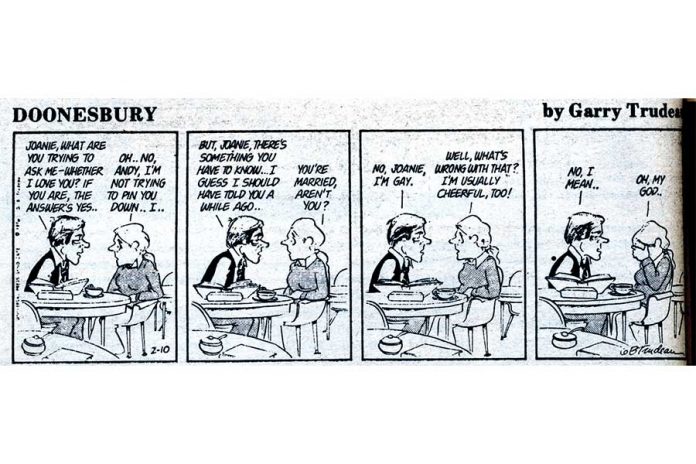

In the March 1976 issue of PGN, M. David Stein wrote about Andy Lippincott, the first openly gay character in a comic strip. A mild-mannered, respectful law school student, Lippincott debuted on Jan. 27, 1976, in “Doonesbury,” the iconic series created by American artist Gary Trudeau. His first appearances in the comic follow his introduction to fellow student Joanie Caucas, a 30-year-old feminist who immediately grows smitten with him. The two chat about legal cases and eventually meet for a dinner during which Joanie is flirtatious and Andy apprehensive. A few weeks later, Andy comes clean and tells Joanie that he is gay.

At the time of Andy’s revelation, the few LGBT characters in pop culture were not given fully realized storylines; most were relegated to supporting or comedic roles. There was no exploration into their sexuality and no discussion about how difficult such a life could be in the 1970s. But their inclusion was important nonetheless. That gays existed beyond predatory stereotypes had to be hammered home to people again and again.

M. David Stein’s article in PGN was not really about Andy’s coming out, which appeared in over 400 newspapers that week. Instead, Stein covered the inevitable backlash. Five of those newspapers’ editors banned the comic strip after Andy’s coming out. Dozens more followed suit. Many wrote that their audiences were not ready to read or discuss homosexuality. That it was in a comic strip was seen as more of a threat because comics were popular. Stein ended the piece with a call for gay readers to voice their opinion on “Doonesbury” to its distributor, Universal Press Syndicate. As always, public response was paramount in promoting and keeping LGBT visibility in the media. Even the filler characters, even the easily forgettable storylines, were important.

At first, it seemed like Andy was heading for that same supporting character obscurity. For the next decade following his debut, Trudeau focused on other characters. At that time, Andy was used only once, for a storyline about Joanie’s career, and then put back into the pencil case. But in the late ’80s, Trudeau introduced a storyline that made Andy unforgettable: he had AIDS.

For two weeks in April 1989, the comic strip followed Joanie and Andy’s reunion in the hospital where Andy was being treated. Andy coped with his illness with jokes about morphine cocktails and White Castle hamburgers, something Joanie found hard to accept. “Andy, how can you joke?” she asks him one afternoon. He replies, glibly: “How can you not?”

When Joanie leaves the room, Andy’s doctor explains to her: “Andy uses humor to soften the rage he feels, and to help him face the abyss. I encourage it because AIDS care is about helping people cope, helping them die with dignity.”

Trudeau didn’t just limit the discussion of AIDS to Andy’s plight. The storylines, which included a character who couldn’t even say the word AIDS, drew intense attention because of a willingness to tackle stereotypes and fears the public had about the disease. The comic also provided a much-needed levity for hospital workers and patients who had seen only sadness. Many AIDS organizations regularly posted the series on their walls and doors. Even Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, then a regular Congressperson, chimed in on the storyline, telling the Associated Press in an Apr. 4, 1989 article that she was surprised it took so long for Trudeau to broach the AIDS issue. “I wish he had done this four years ago,” Pelosi said. “Most of what I’ve seen so far is a little after the fact.”

Andy treated his struggle with dignity, kindness and humor, and the way he handles himself helps the other characters, and the comic’s readers understand that AIDS was not the monster the media and right-wing had purported. When Andy died, in the May 24, 1990 strip, he went out listening to a Beach Boys song, achieving a dream of listening to the record “Pet Sounds” on compact disc.

Andy meant so much to people that the San Francisco Chronicle ran an obituary for him. He is the only fictional character to have a panel on the AIDS quilt. He and the lessons he taught are worth remembering.