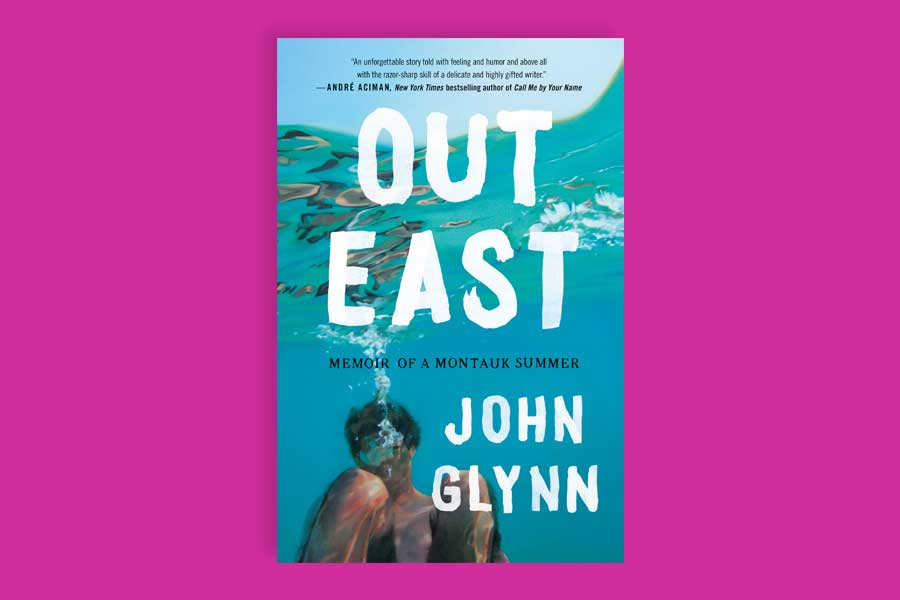

John Glynn’s memoir, “Out East,” set mainly in a Montauk share house in summer 2013, recounts the transformative period in the author’s life when he found himself attracted to men.

As this self-indulgent book reveals, Glynn felt an emotional (and, by extension, physical) connection to a young man named Matt — one of his 29 cohabitants of “The Hive,” the nickname of the communal house he stayed in that fateful summer.

Designed to be a beach read, Glynn’s book features short paragraphs that convey simple facts. He describes his love for his grandmother, Kicki, who passes away. (He really loved her!) He explains the route he takes from Manhattan to Montauk. (Where to transfer to save time.) He itemizes what he packs in his weekend duffel bag. (A bathing suit, T-shirts, etc.)

But little of this information is compelling. Should anyone who bothers to pick up “Out East” get distracted while reading it, they really won’t miss much.

The bulk of the book describes the manic antics of these wild and crazy 20-somethings at the house. They call it summer camp for adults, but few of them are adulting. The “ABCDs” of The Hive are “alcohol, booze, chips and dick.” (The house is one-third women and one-third gay.)

Glynn introduces the major players: Mike and his boyfriend Shane; Ashley, a very attractive young woman; Matt, the guy Glynn is attracted to; and a bunch of others. Most of what they do all summer long is get drunk.

There are descriptions of various bars and clubs they frequent in the Hamptons — The Mem, Sloppy Tuna’s, etc. — as well as what they drink: Tina Juice, Rocket Fuel, Transfusions. (The latter is vodka, ginger ale and grape juice.) They often “pregame” in the house by playing beer pong. Readers could get as drunk as the characters by taking a sip every time Glynn uses a version of the word “pregame.”

But reading about these privileged housemates drinking and having fun is not as interesting as the author seemed to think it might be. That’s because Glynn didn’t write about his friends in a way that makes them as interesting as he thinks they are.

Mike and Shane are experiencing tension in their relationship, especially when Mike starts spending time with a housemate named Parker. Ashley appears to be wise about relationships — she advises Glynn on the rules and laws of attraction — and ponders whether she should participate in a bikini contest. (Spoiler alert: She does!)

Glynn becomes infatuated with Matt, hanging out on the roof with him, sharing music, one’s hand touching the other’s arm … but there is little sense of their special emotional-spiritual connection.

“Out East” is best when the author writes about his feelings for Matt. (In contrast, reading about his anxiety about being lonely and fear of being unloved, while very real, is exhausting.) His description of how he misses Matt on the weekends they are not together, as being pulled by an undertow, is one of the few genuine moments in the book.

Glynn, grappling with his same-sex longings, is afraid to tell Matt how he feels about him. The author also tries several times to tell Mike about his crush and his sexuality, but often chickens out at the last minute. His cowardliness is relatable at first but becomes tiresome the third and fifth times.

The book may be helpful for queer youth to process their feelings — but it also can be seen as a guide for how not to behave.

Glynn and his friends are “hardwired for self-destruction.” He likens what transpires at The Hive to a real-life soap opera — which is hardly a profound observation. Alas, an episode of the low-rent “Jersey Shore” is arguably more dramatic and enlightening than this book.

When Glynn describes “morning therapy” — “the fizzy terrain between drunk and hungover” when the housemates lay talking — the reader gets a sense of the communality of their experience. Glynn writes: “Someone always came through with the perfect line.” But he never explains what that line was, or why it was perfect. Perhaps one just had to be there.

Hence, the greatest flaw in this very-flawed memoir is the author’s inability to take readers into the moments he tries to describe.