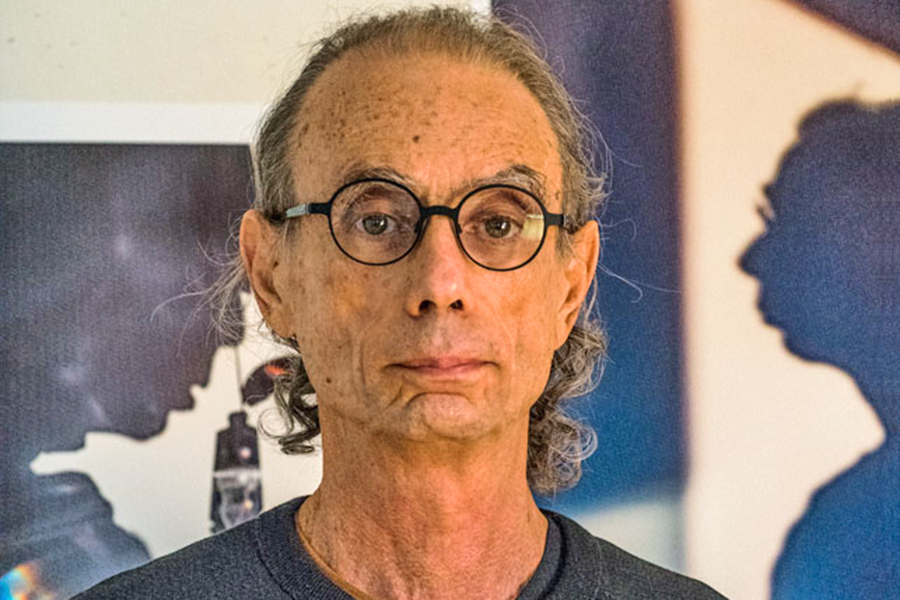

I recently had a chance to go into the Perelman Building of the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the first time. It’s a lovely building and currently housing “Long Light” — an exhibition featuring a collection of photographs from David Lebe.

The exhibition showcases 145 photographs beautifully displayed to honor his different styles developed over five decades. It includes his powerful representations of gay experience and living with AIDS.

Lebe’s experiments with light and paper are beautiful and haunting. His series of pinhole photography shows what can be done with a little ingenuity and a lot of creativity. His skills as an artist and technician are matched by the raw emotion captured in his photographs.

PGN: I understand you were born in Manhattan. Do you come from an artistic family?

DL: Yes. I was born and raised there. My family wasn’t necessarily creative, but they were appreciative of the arts. I don’t know that they were crazy about me going to school for it, but they were still supportive. I went to The High School of Music & Art in Harlem and then the Philadelphia College of Art, which was later renamed the University of the Arts.

PGN: Do you have siblings?

DL: I was adopted, and the only child.

PGN: When did you first discover your love of photography?

DL: I got my first camera what I was about 7 years old. A little Brownie camera I got at a birthday party or something. I was always fascinated by picture magazines and images. As a child, we’d go to museums sometimes and I enjoyed looking at the artwork. And of course being gay, I somehow instinctively knew that being in the arts was a safe place to be. I think that played a role, and I wasn’t particularly good at academics. I’m slightly dyslexic and I had a rough time with school except for my arts classes, where I felt I had an edge. Since I’d always been intrigued by photography, it seemed like a natural choice. I had a small darkroom in the bathroom of our little apartment so I’d started making pictures even before I studied it. Coming home from high school, I’d often stop at the Met and the Museum of Modern Art. They didn’t have photography at the Met, but you could find it at MoMA and independent galleries. Back in those days, there were very few colleges where you could study photography, maybe three in the country. My parents were protective and didn’t want me to go too far, so Philadelphia was the logical choice and that’s how I ended up here.

PGN: Were you out before you came to Philadelphia?

DL: No. I was late to the party! I’m terrible with dates, but I think it was around ’72. I finished school in ’70. I never actually graduated. I was short a few credits. And then in about ’72, I came out to a few friends first. Very quickly after that, pretty much everyone knew in Philadelphia. But I didn’t come out to anyone in New York, where my family was.

PGN: Do you remember your first gay bar?

DL: That took me a while. I used to have panic attacks whenever I got near a gay bar. I can’t remember the first one, but later I recall going to a place called The Steps on Spruce Street. Later still, there was Equus and the DCA Club.

PGN: What made you so fearful?

DL: I don’t know. It was just the time and the atmosphere around me. You know, there were three things that you only were allowed to talk about in a whisper: homosexuality, mental illness and alcoholism. The idea that I might be gay was … it just seemed impossible to me, even though deep down I knew I was. But I told stories to myself. I would tell myself that I was just a late developer and that any day I would start being interested in girls. I felt like a pre-pubescent girl who hadn’t developed breasts yet. I was just behind the curve. By the time I was 15, I knew it wasn’t going away, but I didn’t share it with anybody for a long time. It was a very difficult and painful time for me. I was even suicidal at one point. But when I did finally come out, there was this exhilarating euphoria about me. It was like the whole world was reborn. It was an amazing time. Though I’d still have those panic attacks if I got anywhere near a gay bar, it was like a form of PTSD. It didn’t matter that I was out to everyone I knew in Philadelphia, friends, coworkers, anyone that mattered. It was odd. I had no reason to panic, but I couldn’t control it. By the time I finally began to get it under control, the AIDS epidemic had started.

PGN: Did your artwork help you get through it?

DL: It did. I came out in my art before I ever said anything to anyone. I started making pictures that were, I thought, pretty suggestive — never intending to show them to anyone. But it wasn’t long before I started showing them to other people.

PGN: Were they photos of males or yourself?

DL: Most of them at the beginning were probably images that most people wouldn’t have even read as gay, but I was hypersensitive about it. There’s a pinhole picture in the exhibit called “Wink” and I think of it as my first “out” picture. It’s a picture that I took of a statue that was in front of Memorial Hall. It was a sculpture of two men wrestling. They’re nude, and kind of have their asses in the air. I took a picture of myself standing in front of the ass side, looking at the camera. So it was a subtle nod. And then I took a few nudes of myself and my partners. My work largely comes out of my life. So what was happening was what came out in my work. I didn’t try to hide anything. I didn’t try to be confrontational, but what I did was to never censor my work, to always be open. Even when I was teaching, I was out to my colleagues and to my students. There again, I was too chicken to say anything out loud, but I would show a slideshow of my work and it was pretty apparent. It would be totally dark and I’d be in the back of the class and would come out that way. I did that with every class. This was around 1975 and even though it was an art school, I was the only out teacher there. There were some who were out to their colleagues and would bring their partners to functions, but never said a word in the classroom. When I was in school, I did not know a single out person at the school — at an art school of all places.

PGN: Did you find you had students who came to you for support after learning you were gay?

DL: Oh yes. I had many students come out to me and I was able to help provide them with some information and services. I read the PGN and Au Courant, so I knew of places to send students for help. It was wonderful. There were a lot of touching memories from that time. I’m sure it was helpful to those I never met but who knew of me being gay. Just to be visible.

PGN: It’s funny because you seem to be such a private person, but through your work you were able to be honest about not just your sexuality but also your battle with AIDS.

DL: Yeah. I wasn’t about to go in the closet about something else when that came along. The slogan back then was “Silence = Death,” and it was very true. I had no hesitation, though I didn’t tell the family for a while.

PGN: What happened when you did come out to the family?

DL: It was not easy. I sat in Giovanni’s Room and wrote them a long letter. I didn’t hear from them for two weeks after that, and they normally called at least once a week. They weren’t answering the phone, so I had to drive up to confront them. At first, they acted like they didn’t know, which angered me. It seemed so obvious. It felt like they didn’t really want to look at who I was. They claimed they were shocked. It was a different and difficult time.

PGN: When did you meet your partner Jack?

DL: We met in Philadelphia in 1989. He was the curator of the Scott Arboretum of Swarthmore College. We were both HIV-positive. Then, just a few years after we met, we moved to where we are now, in New York’s Hudson Valley.

PGN: What’s prompted you to move so far away?

DL: Well, frankly, we thought it was our last adventure. Back then, we thought everything was short-term. It was going to be a short-term relationship and a short time up there. It was before the drug cocktails they have now. Our immune systems were compromised and the pollution here was exacerbating the problems. We wanted someplace that was clean where we could grow our own food and eat healthy for the time we had remaining. I sold my house in Philadelphia. Jack cashed in his life insurance, and we built our house there. We never expected to be here this long.

PGN: Yeah. It was scary back then. So many people were dying so quickly, it was crazy. I remember seeing a coworker on a Friday, and by Monday he was gone. I didn’t even know he was sick.

DL: Yes. You couldn’t walk down the street without passing a building or a window with a bulletin or memorial about someone who’d died. They were everywhere. We were lucky in that we didn’t do anything rash like max out our credit cards like a lot of people did, thinking they didn’t have long to live. Jack was more conservative and optimistic than I was.

PGN: That was another area of your work that was raw and real: the pictures of the model Scott showing the Kaposi sarcoma lesions caused by AIDS. That was pretty brave to show at a time when people were trying to hide their status.

DL: Well, he was pretty out there, a writer and a porn star. I met him at a time when I was really shut down, so it was very helpful to me.

PGN: Changing subjects: How does it feel to have a retrospect of your work back here in Philadelphia?

DL: I’ll tell you, we drove into Philly over the Betsy Ross Bridge and the sky was turning with the colors of dusk; the lights of the buildings in the skyline were just starting to twinkle. It was very beautiful. And though it’s changed, there was still a lot of it that was recognizable. We came up the Parkway past the Franklin Institute, and it was very emotional both for me and for Jack. I mean, those were the days of my youth in my 20s and 30s. I loved this city, and it was very emotional being back here. We live a very quiet life in Upstate New York. It was exciting to be here with people who came from all over the country to see my work. Between opening night and all the parties and events we’ve gone to, it was quite intense and very moving. It was a dream in a way.

PGN: It seems that your legacy is two-fold: the impact you’ve made as an openly gay teacher and artist and the technical side as a photographer and the techniques and innovations you’ve developed to create your art.

DL: When I came up as a photographer, it was very male-dominated and macho. It was very buttoned-up. There were all these rules you were supposed to follow to compose a shot. I was always trying to push the boundaries. Despite photographs then having a small section in MoMA, there was still a question as to whether or not it was art. I tried to open it up, make it more like a painting. To incorporate some of the things I’d seen and learned going to all those art museums as a kid. I was always pushing boundaries. I feel good about that and I think it comes through in the show.