Mexico-born artist Ada Trillo had her first exhibition at the Rittenhouse area’s Twenty-Two Gallery in 2017. The inspiration came from her homeland: drug-addicted Mexican sex workers at the “intersection of sympathy, dignity, and hope.”

The black-and-white photographs lent each subject an elegance of line and an air of regality. Since that time, Trillo’s work has been included in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

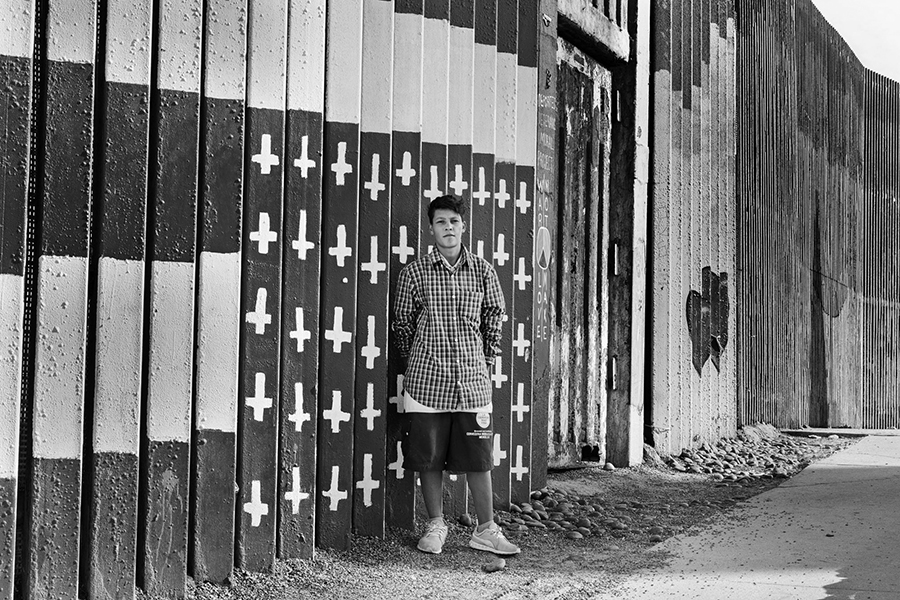

Two years later, with “Chasing Freedom: Migrant Caravan Portraits,” the Philadelphia-based Trillo moves her lens to the currency of life along the U.S.-Mexico border. Here, she continues to find love and dignity among the ruins; a sense of intimacy among the South and Central American refugees.

Trillo found and photographed a group of LGBTQ caravan members from Honduras, including a wedding between two young men. It was a risk taken by all, as gay marriage is illegal in Honduras. Trans and gay Hondurans face violence in their own country and are easily targeted even in a caravan.

One brave soul, “Kevin,” born biologically female, is an example of those who got into the United States. Not everyone will be so fortunate.

La BODA Photo: Ada Trillo

Trillo spoke to PGN about her work.

PGN: With this trip and exhibit, you didn’t start out looking for an LGBTQ angle, correct? What were your initial intentions — personally, aesthetically, politically?

AT: My intention was to document what I saw with photographs. The LGBTQ “angle” wasn’t something I anticipated, but something that presented itself organically. It’s what was happening. When I arrived at [the southern Mexican city of] Tapachula, I met Kevin, who was a transgender man. We became friends and traveled together most of the journey until arriving at Tijuana. He is a friend of a young man I met last summer covering La Bestia, also known as the train of death. La Bestia is a train used by migrants to move from the south of Mexico towards the border towns. Many people strap themselves to the top of the cargo train in order to ride. The ride is very dangerous because the Mexican police as well as organized-crime groups attack the migrants, kidnap them and sometimes kill them. Last year there were an estimated 20,000 kidnappings of migrants in Mexico. The young man who I met while documenting La Bestia got deported from Arizona to Honduras, and he wrote to me in October via Facebook to join the caravan. I joined him and his friends in Tapachula.

PGN: How did these newer efforts and ideas differ from the photos in your first exhibition, the disparate women of your homeland?

AT: They are connected because it’s giving a voice and giving dignity to people that are vulnerable. We need to create an awareness of these important issues and we need to help because that’s how the world will become a better place. A percentage of the proceeds from the work will go to the Minority Humanitarian Foundation, who are doing great things on both sides of the border. I also made a Go Fund Me using one of my pictures to get formula for infants at the Benito Juarez shelter because there was almost none and the mothers were desperate. If we all put our little grains of salt into what we can, things can be better.

PGN: What is the best, most accurate description you can make of meeting this caravan from Honduras and the gay wedding party? And when exactly did this all happen?

AT: The people from the caravan were beautiful, humble people wanting to work, to contribute. Many were facing horrible circumstances that forced them to flee. The life expectancy for trans women in El Salvador is 35 years and there has been a 400-percent increase in the number of trans women murdered there since 2003. The maras (gangs) have taken over the country and the youth. That’s why the caravan had so many unaccompanied minors, because they are recruited between ages 10 and 12 to join the gangs. If they resist, they’re murdered, so the parents prefer for them to leave because it’s safer than staying. Many families seeking asylum, including pregnant women, walk up to 10 hours at a time because they could not get rides. Children with special needs are not getting their proper medicine. We have a humanitarian crisis that needs to be addressed. Again, the idea is to open a space that increases awareness around the human-rights violations of asylum-seekers.

PGN: Who were these two young marrieds, and what was the ceremony like?

AT: I don’t want to say the name of the location, as it just reopened and they offer migrant services there. The ceremony took place on the front porch of the restaurant that was decorated with colorful streamers and ribbons, white roses embellished the ledges, and the [rainbow] flag was beautifully draped in the background. Multiple couples filed down the steps one by one to be married, and as they kissed, rice was thrown in the air. The trans woman in my photograph (a guest, not a participant) caught the flowers thrown by one of the couples. The wedding was a delightful surprise in a time of suffering. We had music and everyone was happy because, in the northern triangle, gay marriage is illegal, so to have the joy and the freedom of finally being allowed to marry your loved one was absolutely beautiful. It’s a beautiful thing that I was able to photograph the event, though I didn’t seek out that particular community. They, like the others who allow me to photograph them as part of my work, are trusting me with their image and I hope I have served their trust. I don’t use long lenses. The people in my photos and I are eye to eye. There is a certain amount of access that I am given as a person of color, as a mother, as a woman.

PGN: How do you see the LGBTQ border struggle as differently dangerous?

AT: Like unaccompanied minors and others, LGBTQ people are more vulnerable for many reasons. In one sense, their visibility makes them targets for abuse and trafficking. A portion of the LGBTQ community got separated in Mexico City and they took buses separately to Tijuana and stayed in different housing because some of the members of the caravan were being abused. This is horrible and just shows how difficult things were and are. Ignorance, lack of respect, intolerance, transphobia and homophobia are common in Central America, and are now being actively promoted by the current U.S. administration. That can be deadly.

“Chasing Freedom: Migrant Caravan Portraits” opens April 5 at University of the Arts — Gershman Hall Studio Theater.