Most people know about the Mariel Boatlift in 1980. But many don’t realize that large number of the more-than 120,000 Cuban refugees that made the dramatic trek to Florida that year were gay.

The stories of how these gay Cuban refugees made their way to this country, and what happened to them once they got here, are the focus of a new exhibition at William Way LGBT Community Center called “With Open Heart and Open Arms.”

The genesis of what has become known as the Mariel Boatlift has its roots in the complicated diplomatic relationship between the United States and Fidel Castro’s Cuba, a connection that had been frozen in hostility and suspicion since Castro came to power in 1959. Attempting to improve the longstanding impasse between the U.S. and communist Cuba, President Carter began loosening some of the travel restrictions to the island in the late 1970s. This was a one-way deal, however, since Castro would not permit Cubans to migrate.

Partly because of Carter’s overtures and also due to severe economic downturn, massive numbers of Cubans began seeking asylum; at one point more than 10,000 aspiring immigrants were taking refuge in the Persian Embassy.

After several months of hostile exchanges between the Cuban government and the various embassies involved, Castro relented. He stated that the port of Mariel would be opened to all who wanted to leave, provided someone was there to take them away. The result was a mass migration.

However, Castro decided to take advantage of the situation to clean house socially, as it were. He dumped thousands of hardened criminals, political prisoners and mental-health patients into the migration, including large numbers of gay Cubans. The Castro regime was, unsurprisingly, virulently homophobic, considering homosexuals to be social pariahs and antithetical to the Revolution. Most gay people, once discovered, were imprisoned.

When word got out about the large number of gay people taking part in the Boatlift, many American LGBT activists and philanthropists stepped up to help with resettlement efforts. “With Open Heart” documents some of these stories.

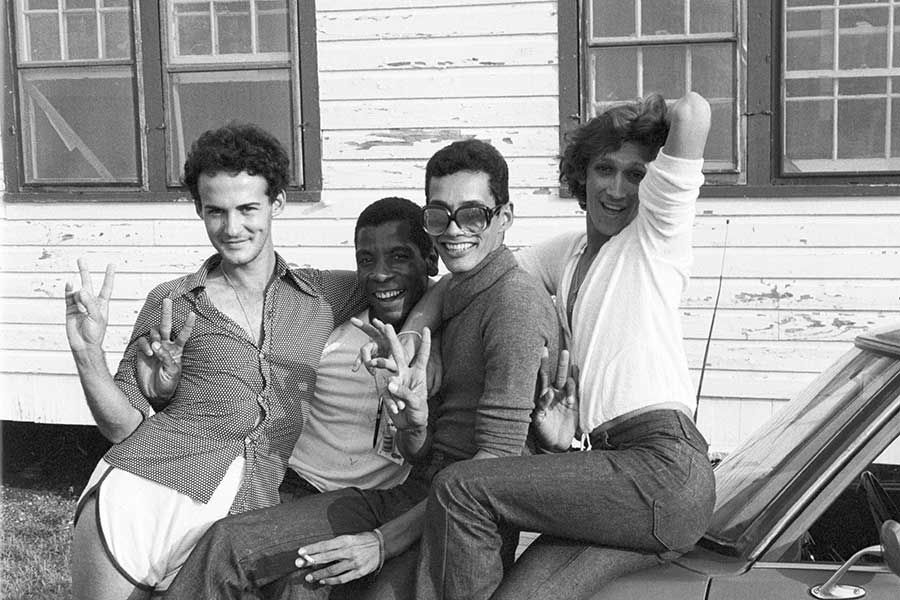

Organized by John Anderies of William Way’s John J. Wilcox Jr. Archives, the exhibition is structured to provide maximum information with a minimum of academic fussiness. There are a fair number of period photographs documenting the lives of some of the Mariel gay refugees, many of whose faces shine with optimism at the prospect of living free and uncloseted in their new home.

Given the complicated politics of gay immigration at the time, officials were not allowed to use the term “refugees” in reference to the Boatlift’s homosexual participants. The term “Marielita” was coined, often used as a pejorative, but like the term “queer” before it, some Marielitas claimed the term as a badge of pride.

The estimates of the final tally of the gay Cubans who made their way to the United States during the Boatlift vary widely, ranging from a low of 1,000 to upwards of 20,000. There were a number of resettlement camps set up to accommodate the influx of people. The one set up near Philadelphia was at Fort Indiantown Gap outside of Harrisburg. The camps were originally managed by FEMA, and later were taken over by the newly formed Cuban-Haitian Task Force, which had been set up to help deal with the ongoing issue of migration from the troubled Caribbean islands.

The Philadelphia branch of the Metropolitan Community Church initiated much of the resettlement efforts for the gay Cubans. MCC helped lead the search for community sponsors to assist the immigrants in becoming official U.S. residents. Many of the immigrants settled in the Cuban neighborhoods of North Philadelphia’s Fairhill section.

This information, and much more, is provided in short historical summaries interspersed with the photographic exhibit. These summaries are presented in both English and Spanish.

These historical summaries also provide interesting follow-up information on what happened to some of the gay Cuban immigrants after they settled into their new lives. For many, resettlement was not an easy process.

One distressing point of information is that the Marielita were hard-hit when the AIDS epidemic reared its ugly head just a few years after the Boatlift. Subsequent research with blood samples taken during the resettlement process showed that many of the gay Cubans had already been infected with HIV at the time of the resettlement in 1980. This proved that HIV had already spread worldwide before it was first diagnosed in the U.S. in the early 1980s.

The exhibition also contains numerous clippings of the press coverage of the Boatlift and its aftermath. Early issues of PGN (then simply called “Gay News”) and its then-rival newspaper Au Courant also devoted much effort to covering the story.

One more important component of the exhibition is the video presentation. The archivists personally interviewed and recorded some still-living survivors of the Boatlift and subsequent resettlement. These survivors provide fascinating and intimate first-person narratives, giving us a glimpse of what it was like to live through such tumultuous times. The video interviews are on a repeating loop, and can be listened to privately on individual headsets.

“With Open Heart and Open Arms” will remain on display through April 27 at William Way, 1315 Spruce St. The exhibition is free and open to the public, and is presented in both English and Spanish translations. For information about gallery hours, visit waygay.org.