Bisexual fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez achieved fame in the late 1960s and early ’70s with his vivid images of prominent models, including Jessica Lange, Grace Jones, Tina Chow Jane Forth, Donna Jordan and Jerry Hall, whom he discovered. And he kept company with The New York Times style section’s Bill Cunningham and designer Karl Lagerfeld.

Now the man described as sensual, seductive, romantic and ahead of his time will be on the big screen.

James Crump’s buoyant, if skin-deep, documentary, “Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex, Fashion & Disco,” opens Oct. 5 at the Landmark Ritz at the Bourse. The film effectively captures the magic of this magnetic, charming and flirtatious figure in the fashion industry.

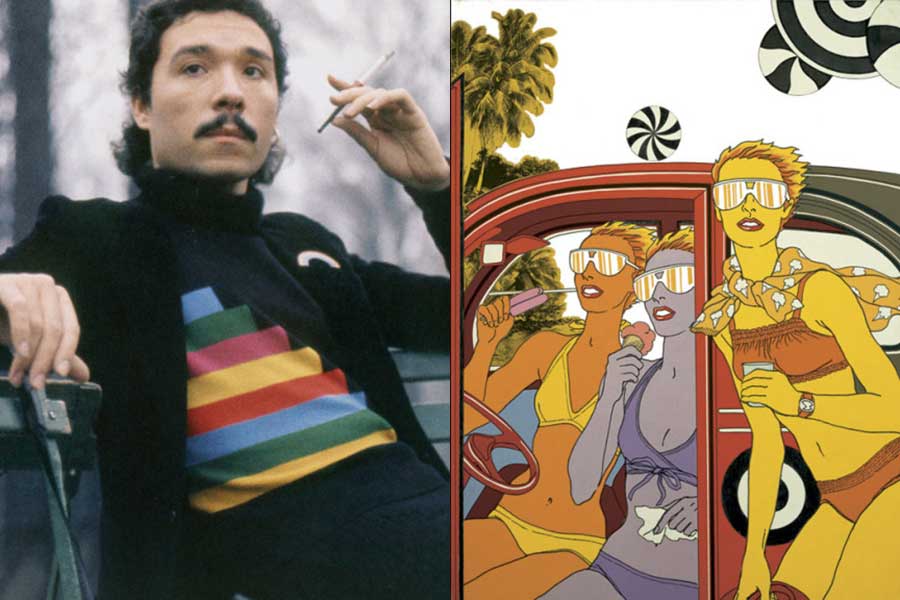

Crump features hundreds of dazzling photographs and film clips of his subject, making it easy to see Lopez’s appeal. The images of him drawing, posing and even mugging for the camera communicate his larger-than-life personality. When someone exclaims that Lopez “looked like a pimp,” photos of the artist sporting a red hat, jacket and pants, along with a cane, illustrate that image. He also loves to dance, as evidenced by a series of photos that bring his body language to life.

“Antonio Lopez 1970” showcases much of the artist’s work using big, beautiful images full of sensuality and sexuality. Joan Juliet Buck, the former editor-in-chief of French Vogue, describes the difference between “rendering” and “recording,” noting that Lopez’s work is so extraordinary because he did the former.

Frustratingly, several of the interviewees are not seen while they are speaking. This makes it difficult to determine the source of certain stories except through voice recognition. Many anecdotes are relayed by noted raconteurs, including Lange, who provides an amusing account of how she reconnected with Lopez after he lost her phone number. Patty D’Arbanville recounts with infectious enthusiasm how she danced and drank too much with Lopez.

Cunningham is particularly revealing in his storytelling: He recounts a night Lopez was unable to find the right model for a dress — even forcing Cunningham to try it on. Still unable to get it right, Lopez went out and found a hustler with the perfect body to wear the dress in a way that would allow him to sketch it properly. Such was his vision and talent.

His sketches of Hall, described as “the ultimate Antonio girl,” support this characterization. Viewers may want to see even more of Lopez’s work, as the film focuses as much on his life as it does his art.

That life unfolds during the heady, early days of gay liberation. Max’s Kansas City was a place to be seen and dance, and Lopez and his entourage, which included the models and makeup artist Corey Tippin, rivaled the clique that was Andy Warhol and his followers. As Lopez’s various friends recount their experiences — begging to get into the club or observing wild behavior (if not performing it themselves) — the film generates a nostalgia for the pre-AIDS, pre-Instagram era.

Crump reveals that Lopez was attractive to everyone he met. He slept with both women and men, but preferred men. He also maintained a five-year relationship with Juan Ramos, whom he met at F.I.T. The two students quit school together and embarked on a professional career that outlived their relationship. Ramos was refined and intellectual, and a formidable partner for the mercurial Lopez.

“Antonio Lopez 1970” gives Ramos his due, emphasizing his importance in their collaboration. Ramos’ role in Lopez’s life and career was interesting enough to merit even more prominence in the film.

There are discussions of Lopez being hypnotized to cure his inability to work; his near-marriage to Hall; his dancing at Club Sept in Paris and going off to Saint Tropez. There is little about his family. His father was a psychic and his mother had difficulties with her son’s sexuality. One interviewee describes Lopez as being addicted to sex. He eventually contracted AIDS and died in 1987. (Ramos died eight years later, also of AIDS.)

Despite all the fond memories, “Antonio Lopez 1970” never delves very deep. Lopez’s life looks mostly fun and exciting. But Crump never really connects the dots to provide a greater understanding of the importance of the illustrator’s contributions to fashion and culture. He just seems to revel in its superficial beauty.

For some, that may be enough.