Lost in the celebrations of this year’s Pride was the death of a historical crusader for LGBT rights. The passing of Dick Leitsch was a reminder of the role secret societies played in mid-20th-century America.

Leitsch, who died June 22, led the New York chapter of the Mattachine Society, which represented the beginning of LGBT advocacy and support in the United States.

Founded in 1950 in Los Angeles, pre-Stonewall Riots, Mattachine grew from an underground social gathering into a public-service agency that’s now celebrated through modern-dance parties. Harry Hay, a man of many tastes and orientations, led the society at its inception.

The Mattachine Society existed during a time in America when it was not possible to be openly gay.

In the time before the Stonewall riots of the late 1960s, many gay men and women were living double lives in opposite-sex relationships. It took a radical fairy like Hay to establish the Mattachine Society as an important and viable networking group. Under his reign, Mattachine’s existence was characterized as a masquerading society of fools.

“In those days, the late Sen. McCarthy was carrying on in Washington and seemed to be unable to differentiate between a homosexual and a communist, and many reacted very strongly to this,” Leitsch said in a 1969 radio interview with WNYC.

Leitsch died of liver cancer at a Manhattan hospice. He was 83.

Mattachine Society members were groundbreaking activists. They were brave men willing to organize in secret, knowing they could face disastrous outcomes if their sexuality was made known to the public.

“Mattachines were court jesters of the 13th century,” Leitsch told WNYC. “And they wore funny masks and they acted silly, but underneath the silliness, they were speaking truth to the king and sometimes they were the only people in the kingdom who could get away with it.”

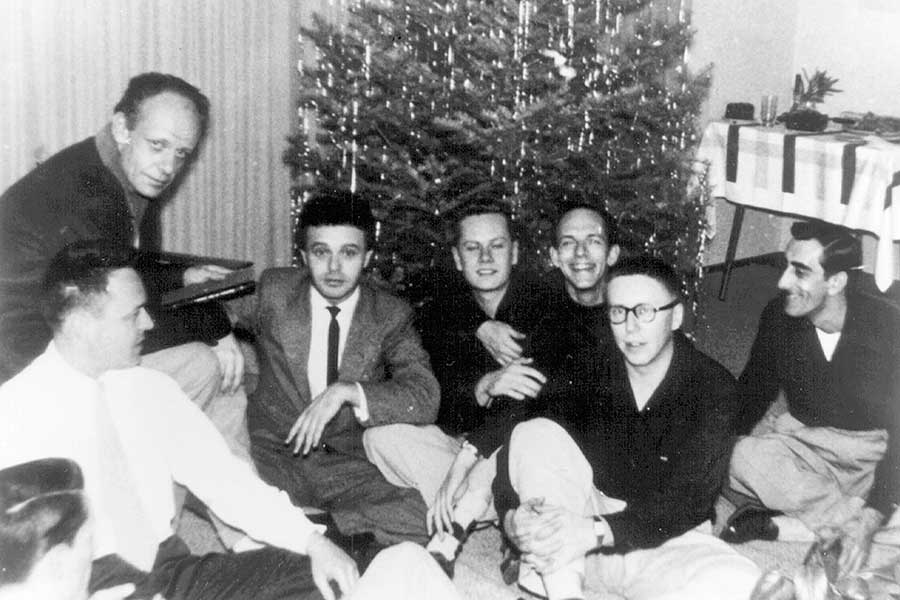

Archival documents and notes of the group’s membership are still rather difficult to obtain. Papers on the Mattachine Society can be found at the One Archives at the University of Southern California. The archives — the largest repository of LGBT materials worldwide — have credible and extensive documentation of this once-secret society. Documents include notes from business- and planning-committee meetings. There is also a photograph from a holiday party showing Hay — one of the participants in Alfred C. Kinsey’s famous study of sexuality — and seven other men sitting around a decorated tree. Another file contains audio from a 1961 hearing on homosexual rights in Los Angeles.

Martin Meeker, 47, is the director at the Oral History Center at UC-Berkeley. He has researched the Mattachine Society under the leadership of Hal Call and Don Lucas.

“Mattachine Society was run by people who recognized that the greatest problem faced by gay men and lesbians was their lack of access to information and their isolation from one another,” Meeker said. “Under the leadership of Hal Call and Don Lucas, the Mattachine Society sought to spread objective information about homosexuality and end the isolation of gay people across the country.”

Hay, an avowed Communist, led the Mattachine Society in 1952.

“By 1954, Hal Call was allowing his name to be printed in the San Francisco Chronicle as the head of this homosexual organization,” Meeker said. “He was a publicly out gay man, probably one of the first in the country’s history. To me, that is the definition of a radical act.”

As the Mattachine Society raised its profile with magazine publications and social services, the 1960s arrived with winds of change. On the East Coast, it gained recognition with the 1966 “Sip-In,” in which members challenged bars that refused service to gay people. The bars justified this practice as refusing to serve “disorderly” patrons.

The Sip-In was a challenge to the State Liquor Authority’s discriminatory policy of revoking the licenses of bars that served gays and lesbians.

“At the time, being homosexual was, in itself, seen as disorderly,” Leitsch told The New York Times in April 2016. The Sip-In is widely regarded as a precursor to the Stonewall Riots.

Meeker’s work and papers on Mattachine focus on the 1950s, when two men joined forces to wrestle control away from Hay and move the Society in a different direction.

“Hay was a communist,” Meeker said. “He was more politically and economically radical than Hal Call and Don Lucas.”

Meeker said Call and Lucas were “Cold War liberals” adding that some historians have mistaken the pair as “conservatives.”

The tension between Hay’s administration of Mattachine — what Meeker termed a “foundation” — and Call and Lucas’ tenure is still reflected in today’s philosophies.

“They both believed in some version of progressive social change, but their visions of how to bring about progressive social change were profoundly different,” Meeker said.

In New York, a more modern way of recognizing Mattachine unfolds every month at Julius, the city’s oldest gay bar and site of the famous Sip-In. Leitsch led the Sip-In protest on April 21, 1966, telling the bartender at Julius that they were homosexuals and wanted a drink.

There is a famous picture showing the bartender with his hand covering the glass as Leitsch places his order.

“That photograph was in the Village Voice and led to the end of that bar,” said acclaimed screenwriter and director John Cameron Mitchell, speaking to Mirror Magazine before Leitsch’s death and calling the Mattachine leader “an inspiration.”

Julius’ rich history is rightfully acknowledged once a month at a night set aside for the Mattachine. These parties are the brainchild of Cameron Mitchell and PJ DeBoy, collaborators on the 2006 feature film “Shortbus.”

Crafted out of a three-floor stucco building, Julius took its place on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

“It’s the only building in Manhattan I’ve seen stucco on,” Cameron Mitchell said. “It’s now a National Landmark building, which is sad, because the exterior is still ugly.”

Cameron Mitchell said today’s Julius is modeled after an old pub and still serves burgers. It’s his neighborhood bar — “my living room,” he said. At one time, however, Julius was known as a place where young guys met older men.

“It was a hustler bar in the ’80s and ’90s. And then those hustlers got as old as their customers.”

The 55-year-old Tony Award-winning director could not resist dismissing former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

“Giuliani came in and, in his view, ‘cleaned these up,’” Cameron Mitchell said. “When really he was just a bully and homophobe and he tried to shut down a bunch of dance parties … just because he’s like that.”

Still, Julius has endured. The oldest gay bar in New York City is the site of celebrations and parties. And thanks to pioneers like Leitsch and the Mattachine Society, no one will be refused a drink based solely on their sexual desires. n

John Cameron Mitchell organizes the monthly Mattachine party with Angela DiCarlo and Amber Martin. He collaborates with bar owner Helen Buford for the annual Sip-In celebration. Julius New York is at 159 W. 10th St. in Manhattan.

Jake Lewis and David Altermatt contributed to this report.