Lesbians exist.

Lesbians, like gay men, have always existed.

If there is a singular lesson to be learned this LGBT History Month, it is that lesbians didn’t just appear suddenly in the 20th century as anomalous figures with no antecedents. Lesbians have lived and loved and had bodice-ripping passionate sex for millennia.

One of the most contradictory aspects of modern queer culture is the premise that any woman who has kissed a girl and liked it (and perhaps made millions singing about it) gets to claim queer status like a Girl Scout badge, while millions of women who lived quiet-yet-obvious lesbian lives for decades in previous centuries have had their lesbianism erased and their sexuality — their very-real, passionate, physical sexuality — neutered.

In a brutal irony, the erasing of lesbian sexuality has been done most effectively by female academics who hesitate to define same-sex relationships between women as sexual, for reasons that are wholly rooted in male contrivance of female sexuality and the male gaze on it. The theory that women never performed sexual acts together before the 20th century is appallingly smug, and not a little homophobic.

And yet that theory persists.

There are points to be argued for why this is wrong, and which lead us from ancient times to the beginning of the 20th century.

The fear of uncontrolled female sexuality has raged throughout history. And throughout the world, corrective rape of lesbians is endemic — including in the USA. The emergence of the #MeToo movement has overlooked lesbians, but they are its shadow victims.

Within this construct of controlling women’s bodies and sexuality, lesbian orientation is the most fearsome of all sexualities because men are wholly elided from it. If a woman doesn’t need a man for sexual pleasure, then the driving societal function of maleness — heterosexual sex — is thrown into question. So, too, is the predicate for enforcing compulsory heterosexuality upon women.

Every woman, regardless of her orientation, knows from a young age that lesbians are a trigger for men. The most common retort when a woman rejects a man’s advances or catcalls is to call her a “dyke” or “lesbo.” It happens every day, everywhere.

This lesbophobic, misogynist and blatantly ahistorical erasure of lesbian sexuality is similar to the erasure of all autonomous female sexuality: Women’s sexual desire has always been viewed, discussed and portrayed within the construct and purview of the male gaze and, as such, has never seemed complete without the intrusion of a male into that space of wholly female desire.

The trope of a male entering onto the scene of a lesbian sexual coupling just in time to “complete” the sex has been recorded in erotica and pornography since at least the 17th century in the West, and far earlier in Asian erotic art.

One of the most notorious depictions of lesbian sexuality occurs in John Cleland’s infamous erotic novel, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, more commonly known by its smutty name, Fanny Hill, published in 1748. (In British slang, “Fanny” means vulva, hence Fanny Hill was a cheeky play on mons veneris.)

In Cleland’s novel, Fanny engages in lesbian sex with Phoebe, a bisexual prostitute. Fanny also witnesses — and describes vividly — other lesbian sex scenes. The novel was first banned in the U.S. in 1821 in Boston, and may have been a progenitor for the term “banned in Boston.”

Heterosexuals have questioned, “Who is the man?” in lesbian relationships, as if there must be a male-female dynamic for the sex and the relationship itself to be fully functional. Butch lesbians have been described and dismissed as pseudo-men, when in fact butch lesbianism is nothing of the sort. In medicalizing texts in the 19th century, there were attempts — failed — to determine whether the genitalia of butch lesbians differed from that of femme-presenting lesbians. Of course there was no difference.

In recent revisionist history, some butch lesbians have been rewritten as trans men when they were lifelong gender-nonconforming butches who identified as female. Conversely, femme-presenting lesbians have had their sexuality written off in Freudian terms as unevolved and infantile.

In literature and popular culture, femme-presenting lesbians have most frequently had their sexuality conflated with bisexuality, a wholly separate orientation. This common conflation has served to erase both lesbians and bisexual women in so many different ways.

Initially, the colonies had sought to imprison lesbians. The criminalization of same-sex female relationships followed that of English common law. How often it was actually enforced is unclear. But in the U.S. alone, there were laws as early as the 17th century against lesbianism. If there hadn’t been examples of lesbians and lesbian sex, why the laws prohibiting it?

In 1636, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Cotten proposed a law prohibiting sex between two women, punishable by death. The law read: “Unnatural filthiness, to be punished with death, whether sodomy, which is carnal fellowship of man with man, or woman with woman, or buggery, which is carnal fellowship of man or woman with beasts or fowls.” There is no record of this law being enacted.

In 1649, in Plymouth Colony, Sarah White Norman and Mary Vincent Hammon were prosecuted for “lewd behavior with each other upon a bed.” The trial documents are the only known record of sex between female English colonists in North America in the 17th century. Hammon, who was the younger of the two, was given a formal admonition, but Norman was convicted. As part of her punishment, she had to allocute publicly to her “unchaste behavior” with Hammon.

In 1655, the Connecticut colony passed a law criminalizing sodomy between women (and men). In 1779, Thomas Jefferson proposed a federal law that included lesbian and gay sex. The law read: “Whosoever shall be guilty of rape, polygamy, or sodomy with man or woman shall be punished. If a man, by castration, if a woman, by cutting thro’ the cartilage of her nose a hole of one half inch diameter at the least.”

Lesbianism has been perceived by many — and Sigmund Freud perpetuated this misperception — as a phase of female sexuality that women grow out of. Freud wrote about schoolgirl crushes and teenage experimentation with lesbian relationships as a stepping stone to “true adult female sexuality” — heterosexuality. (Ironically or not, Freud’s daughter, Dr. Anna Freud, was in a lesbian relationship with child psychoanalyst Dr. Dorothy Tiffany-Burlingham for more than 50 years.)

Is language the problem? It’s true that the terminology itself is fairly recent. “Homosexual” was first coined in the mid-19th century in an 1869 pamphlet written by Karl-Maria Kertbeny to decry anti-sodomy laws in Germany. In 1886, Richard Krafft-Ebing, the noted German psychiatrist, coined the terms “heterosexuality” and “homosexuality” in his work Psychopathia Sexualis.

The term “lesbian” was first seen in poems by men in the 1860s, and then more commonly as a medical term for lesbian sex in 1890. The term “Sapphist” occurs earlier, in early 19th-century poetry and literature.

But without the examples of actual lesbians, where would the language come from? The Greek poet, Sappho, whose birthplace of Lesbos spawned the term “lesbianism” and whose name has become synonymous with female homosexuals — Sapphists — was born in 630 B.C. The relationship of Ruth and Naomi in the Bible and Talmud, the oft-cited verses in Leviticus as well as St. Paul’s comments on same-sex relationships in Corinthians all signal lesbianism as a real — and definitively sexual — fact.

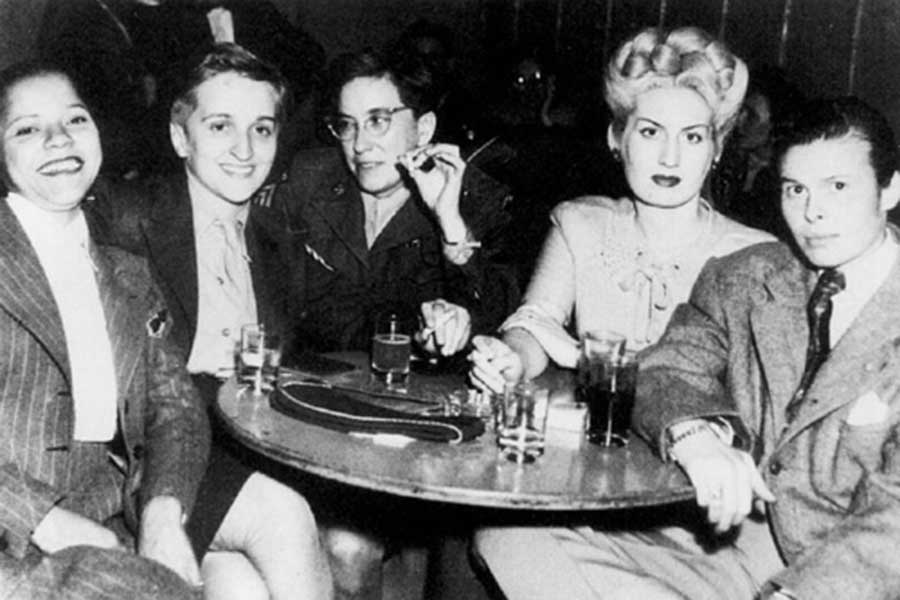

At the turn of the last century, Toulouse-Lautrec and other French and German post-Impressionists incorporated lesbians into their work as denizens of a Bohemian demi-monde. In Paris, Amsterdam and Berlin, communities of lesbians were thriving, albeit in underground communities, which by the turn into the 20th century would include large enclaves of American women — expatriates whose names are now revived each year during LGBT History Month as veritable monoliths in our compendia of writers and artists: Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Romaine Brooks, Djuna Barnes, Natalie Barney, Josephine Baker, Renée Vivien, Ida Rubenstein and more.

While these women fled the U.S. and the mores that made it difficult for them to live the openly — some would claim flagrantly — lesbian lives they led in the U.S., there remained hundreds of thousands of lesbians in America, leading very different lesbian lives, yet not the neutered lives we have been led to believe.