Old City’s 12 Gates Art Gallery is giving Philadelphia an eye-opening look at the works of three Pakistani queer artists this month.

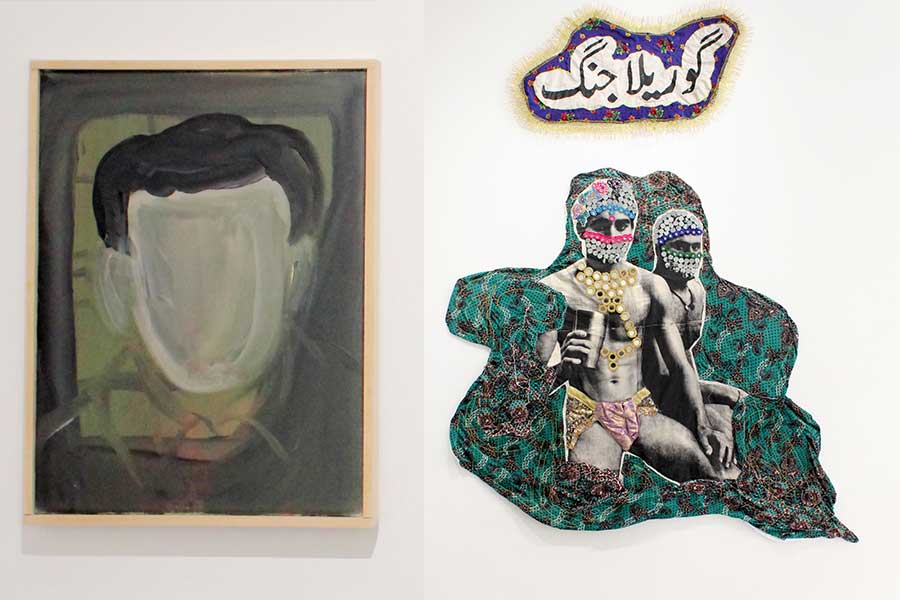

Titled “Unruly Politics,” the exhibition borrows its name from a work of art by Indian queer activist Akshay Khanna and examines notions of queerness, sexual identity, the accompanying political expectations and what that means in this day and age. The exhibition features works by artist, performer and drag queen Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, artist and writer Aziz Sohail and artist and educator Abdullah Qureshi.

PGN: Why is an exhibition like this important to you as an artist?

AQ: If you look at the history of art in Pakistan over 70 years, it is clear that in the earlier decades men predominantly painted women. Fast-forwarding, this was radically challenged in the ’80s by feminist artists in reaction to the Islamization of General Zia’s dictatorship. While the male body has been used sensuously by many artists (mostly men, interestingly), until the early 2000s, it was only Anwar Saeed who addressed queer identity and desire openly. Today, we see more and more artists exploring, examining and complicating what queerness means within the context of Pakistan. As an artist, what is most important to me is being part of this collective moment and contributing to that dialogue through this exhibition.

AS: This is my first exhibition as an artist and I am glad that the dialogue has begun on this important issue. We are definitely part of a broader flux of artists working around queerness and sexuality within Pakistan. For me, personally, this exhibition is also a complex look at this dialogue rather than just presenting the Muslim “other” in the USA.

ZAB: This exhibition represents a broad range of how desire and desirability plays out within queer/gay male South-Asian contexts. It brings to light its shifting nature, its ability to travel through borders, geography, time and space and it also opens up the conversation to its more troubling sides. The three of us work together not only because we enjoy doing so, but also because in doing so, we complicate the conversation. A great deal of discussion around queerness as it relates to Islam and/or Asian-ness in general is dominated narratives of victimization, and as Aziz said, othering; the queer subject as under the oppression of the heterosexual Muslim or Pakistani, or Arab, Iranian and so on. It pits “us” against them and makes us palatable to an American audience, and frankly this conversation isn’t so simple.

PGN: Do you consider your works of art in any way provocative?

AQ: On a personal level, it is never my intention to be provocative. I like to think that through my art, I’m simply stating my truth or narrating experiences. Having said that, I’m aware how our artistic positions as a group challenge and destabilize the dominant narratives that surround Queer and Muslim identities. Mainly because even as three artists, we don’t necessarily see eye to eye with each other, and thus resist being caged in a box. Perhaps, in that sense, the art can be seen as provocative.

AS: I think my work isn’t necessarily more or less provocative than any other artist. I think it is commenting on current matters and is very much talking about a global politics of sexuality and body as experienced by myself as a Pakistani in relationship to the West.

ZAB: I don’t consider my work provocative. Maybe the conceptual framework around it is, but the work itself is designed to speak to multiple audiences. It contains no explicit nudity and glides between playfulness and seriousness. Being able to bring people into the conversation is more important to me than being provocative; however, it also depends on your worldview and the lens you use to see the work.

PGN: Do you think your works will be viewed or interpreted differently when viewed by people outside of Pakistan?

AQ: Certainly. I feel when exhibiting in Pakistan, there is never really a need to justify what being Pakistani or Muslim means. And thus, when one has conversations, artistic or otherwise, then there is the possibility for them to be more complicated and layered. Showing outside Pakistan, in particular the U.S., my understanding so far is that it is very hard to escape reductive categorizations that result from reading queer and Muslim identities from the lens of politics and the “other.”

AS: I agree with Abdullah here. I also think that this work was created very much for both a U.S. and a Pakistani audience, and so in that way was specific to the space itself. I think many globally would be able to relate to or understand this work.

ZAB: Completely! We all use visual signifiers and language that settles in different ways in different contexts, and I think in the arts this is not spoken about enough. There is an idea that somehow artists must be universal and in my opinion that is a hard reach. We all come from different places and are therefore inspired by the societies and places we live in. In regards to my work, Pakistani audiences can read the text that I use; it no longer is relegated to a decorative piece. The bulls, the models, the fabric, trimmings and so on take different meanings. They are recognized differently. Many of my aesthetics take from popular craft traditions seen in wedding halls, religious processions, celebratory and mourning ceremonies. Here in the United States, I play with boundaries and limits to accessibility. It excites me to know that there are some things this audience cannot understand and other things that might settle immediately and others that are understood in an entirely different way. This is what it means for me to do the work I do, to understand how I, as a body, shift contexts, and as I do, so does my work.

PGN: What do you hope people will take away from seeing your art on display?

AQ: “Darkrooms: Retracing Childhood Memories” is a series of work where I explore the relationship between a traumatic past, in particular sexual abuse, and sexuality. It is uncomfortable and maybe even painful. But my hope is that by addressing this, we can have conversations on the different experiences that continue to feed into our sexualities.

AS: To think in more complex terms about the issue of queer identity and how it shifts and negotiates in different countries and spaces. I am also very interested in looking at the border itself and what it means to cross or be encapsulated within it.

ZAB: That they may start to think more deeply about the meeting points of sexual, cultural and religious identity. Since my work exists in the realm of queer Muslim futurism, where queer Muslim bodies claim space in a history of the future, I encourage my audiences to find a space in which we can envision a different world order.

“Unruly Politics” is on display through April 26 at 12 Gates Arts,, 106 N. Second St. For more information visit www.twelvegatesarts.org.