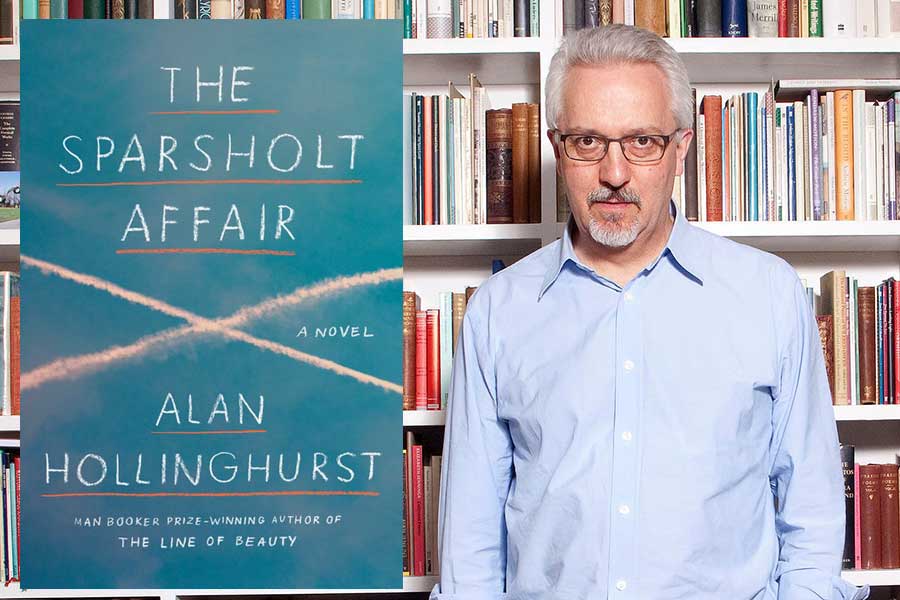

Alan Hollinghurst, who won the Mann Booker Prize in 2004 for his novel “The Line of Beauty,” will be at the Free Library of Philadelphia March 27 to discuss his latest book, “The Sparsholt Affair.”

The title makes the new tome sound like a spy novel, and it is in the sense that it opens with four Oxford upperclassmen in the 1940s spying through a window at David Sparsholt, a handsome freshman doing exercises in a “gleaming singlet.” Soon, three of the men meet Sparsholt. One befriends him, one sketches him naked, and one has designs to sleep with him.

However, the next four sections of this meaty novel feature Sparsholt’s gay-artist son, Johnny, through the remaining decades of the 20th century.

Hollinghurst chatted via Skype from London about his new novel.

PGN: “The Sparsholt Affair” opens at Oxford. You went to Oxford. What were you like as a student?

AH: I was idle, but I got by. I don’t think I was terribly happy as an undergraduate. I didn’t come out until my third year. I think that made a difference, unsurprisingly. It was a time when I was generally having a crush on someone who was unavailable. Oxford is permeated with a sense of longing.

PGN: I like the various intense friendships that develop over the course of the novel: Freddie and David at Oxford; Johnny and his contemporary, Ivan, in London. Can you describe a relationship that impacted you strongly?

AH: I did make one or two friends at Oxford who remain close since. One was Nicholas Clarke, who was one of the first to die of AIDS in 1984. He was a dramatically out gay man, who pushed me not to be so cautious. He took me around gay bars and clubs, and showed it was possible not to mope around. I dedicated this book to Stephen Pickles. He is a reader, and an exacting one. He goes through my books paragraph by paragraph, tearing them apart. We go back 45 years. He knows me so well and has for so long. If I’m not being true to myself, he’ll pick up on that immediately.

PGN: You employ a confident, confidential tone in the storytelling. You also create a series of interconnected chapters but leave the title episode — a scandal — hinted at, but never fully revealed. Can you discuss your approach to the story, which asks the reader to do some recalibration?

AH: I’m fascinated by the personal nature of novel reading. The reader makes it up and pictures things for themselves. The degree of collaboration the writer exacts from the reader interests me a lot. This book and my previous novel, “The Stranger’s Child,” have narratives with big gaps. I think I’m more drawn to these fragmented narratives because I’m trying to capture [the] nature of experience, where so much is unknown, forgotten, unresolved. The classic tendency is to explain and resolve. It’s a high-wire act to maintain interest.

PGN: I like the observant details you include; they inform the characters but also offer wisdom about people, desires. Can you talk about how you observe people?

AH: Johnny’s a change from my earlier protagonists, in that he’s not literary. Most of my characters observe through a scrim of literary references. He’s not; he’s watching and drawing. He says very little in the whole book, but he’s always watching. The main character is the eyes, [where] you see the world of the book, so you need openness and attentiveness. It’s one of my main pleasures: describing. It’s getting the presence of people — the voice and gesture, less their appearance. David is all appearance. You know some of Johnny’s features — his long hair. It’s stimulating and inviting the reader to finish the character, themselves. You encourage the reader.

PGN: You offer considerable thoughts on beauty, masculinity and vanity in this as well as your other novels. Can you explain your fascination with beauty and why you return to it in your work?

AH: It’s something I’ve written about all along. It’s a preoccupation with beauty and appearance. I’m interested in appearance and what’s behind it. The social comedy is speculating what people are thinking and feeling by what they are actually saying. The aesthete in me is beguiled by surfaces. “The Line of Beauty” is about an innocent young man who falls in love with two men because they are very beautiful, without knowing much about who they are or their interest in him. David, in “Sparsholt,” is someone we barely know. He disappears for large periods. He’s a blank onto which other characters project their desires. That is a classic Oxford saying, that beauty sends shockwaves through his generation, but they may not be someone you want to spend the rest of your life with.

Alan Hollinghurst will appear 7:30 p.m. March 27 at the Free Library of Philadelphia, 1901 Vine St. Visit http://bit.ly/2IAyHrt to purchase tickets.