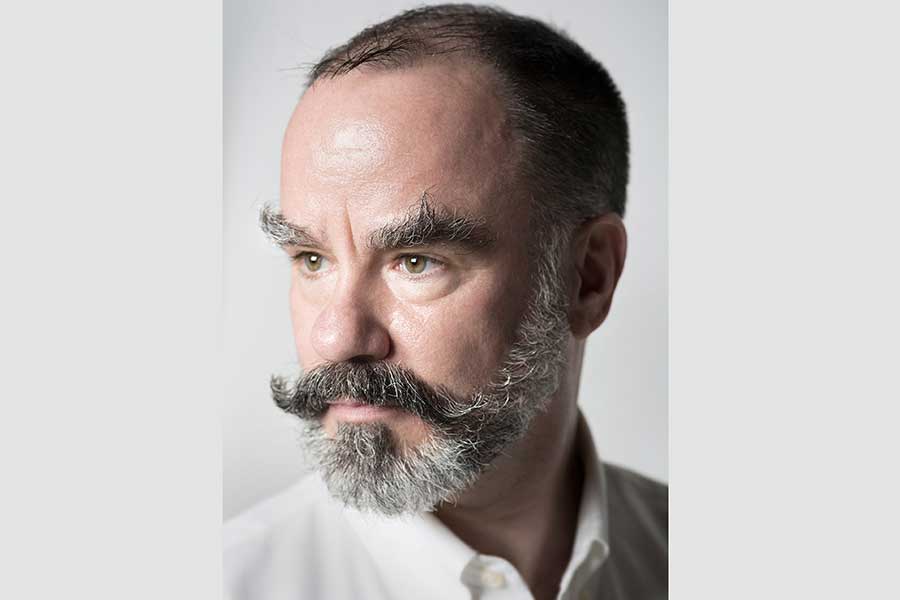

Seán Curran has been dancing since he was a wee lad. After several years as a lead dancer with the renowned Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, he struck out and started Seán Curran Company in 1997. Since then, the group has traveled the United States and the globe performing and teaching a wide repertoire of dance.

This weekend, Curran brings his company to Philadelphia to perform two exciting works for NextMove Dance Presents. We caught up with the delightful Curran on tour.

PGN: Give me the 411 on Seán Curran.

SC: I’m an Irish-American guy, born in Boston. My parents were immigrants. I grew up doing Irish step dancing, which was how I made my way to dance. I spent my formative dance years with Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. I spent four years with the New York original cast of “STOMP.” Then it was time for me to do my own thing, so I started my company and we’ve been going strong for almost 20 years, which is remarkable because it sometimes seemed like Sisyphus pushing the rock up the hill every day only to have it roll down the next day. But I love making dances and collaborating with dancers. I love giving dancers a place to dance and to earn a little money. I’m certainly not able to pay a living wage or pay them year-round but I do my best.

PGN: Tell me a little about your dancing.

SC: I’m happiest when I’m responding to music. Music is like a best friend in a way. I’m not a musician, but I’m a music-driven choreographer. I’m 54 so the identity is changing; I was a performer, then I was a performer/choreographer, performing with a company then forming a company. Now I perform less, though I will be dancing in Philadelphia.

PGN: Let’s go back to little Seán in Boston. Were you shy or were you always an extrovert?

SC: I was pretty extroverted and the reason that my mother took me to Irish step dancing was one, because I was a hyperactive kid and two, an aunt — the one who paid my mother’s way over from Ireland — told her, “You should take him over to step lessons. It’ll knock some of the taspy out of him,” taspy being an Irish word for energy. So Saturday mornings, we went to a VFW hall — it was a dollar a lesson — and learned jigs. My mom was really smart; after dinner, after we made tea and did the dishes, she’d send us to my sister’s bedroom where the record player was. She’d set a baking timer for an hour and we’d have to practice our steps and reels and hornpipes for that hour. I thought, Our mom loves us, she wants us to be really good, but later she told me, “I just wanted you tired out so you’d go to bed!” I was a pretty over-the-top kid. I went to parochial school and I decided I wanted to be a nun, go figure. Then I decided that I should be a Christian brother. I became quite pious and prayed all the time, didn’t miss a day of school through all of fifth grade and got this red leather box with a ribbon on it. I was happy until I opened it and it was a crucifix. That was a disappointing gift so that was the end of that. Then I asked my parents to send me to public school. I was being teased a lot and for some reason I thought it would be better at public school. It wasn’t.

PGN: Why were you being teased?

SC: Well, I was gayer than pink tea, as the British say.

PGN: Was being first generation ever a problem? I know at one time the Irish were victimized as the unwanted immigrant.

SC: No, the biggest worry for my sister and I was what to do if something happened to our parents. Would we have to take their bodies back to Ireland or could they be buried here? As a kid, I always felt there was something special about being first generation, that my parents were from another place. Every other summer we’d go “home,” as they called it. They called my father Mr. Ireland; he was more Irish than most of the people still living there. My father had Aunt Mary and my mother had Aunt Sally, who paid their way over on the condition that they get a job and save money to bring the next wave of family over. As an adult, I learned that they told my parents, “Our people are maids and nannies and janitors” but, to my parents’ benefit, they said no to that. My father went to night school and worked his way up to be able to buy a single-family house and live the American dream. I remember the day they got their citizenship and how proud we all were. Now, being Irish-Catholic, I experienced a lot of homophobia. When I was 11 or 12 and started getting an inkling of what was going on with me, my first thought was, Oh, how am I going to find an Irish boyfriend? I thought the only way my parents would continue to love and accept me was if I could find a nice Irish boy.

PGN: What did they do?

SC: My dad came here when he was 15 and he mowed lawns, shoveled snow, worked at a grocery store, drove a bread truck — anything he could do to make some money. He wound up as an account VP at what would have been called a food brokerage, something like that. The company car was a station wagon and he’d schlep cases of stuff like Green Giant vegetables or Skippy peanut butter to the stores. He wasn’t athletic but he loved soccer and organized Irish soccer leagues. But what he really loved was a weekly Irish radio program he hosted called “The Sound of Erin with John Curran.” My mom was pretty much a stay-at-home mom until we were older and then she worked at a Hallmark card shop. She had what they called “mother’s hours,” from about 10 a.m.-2 p.m.

PGN: Often a boy’s interest in dance is looked upon as a sissy thing. Do you think being able to enter through a cultural route made it any easier?

SC: Well yes. The weird progression is that my sisters and I danced in St. Patrick’s Day parades and parties, weddings and we competed in what’s called a feis, which is a Gaelic word for festival. We were pretty good. My father loved the Irish dancing, but in high school I discovered musical theater. I had a great English teacher who directed all the musicals; she’s in her 90s and we still exchange Christmas cards. She asked me to choreograph “Bye Bye Birdie,” and I asked her what that meant. I didn’t even know the word so she just told to make up dances for the show. I watched a lot of Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire and used mostly Irish jigs to choreograph “Bye Bye Birdie” but she didn’t care and I didn’t know any better! The following year, she hired a choreographer so that I could learn how it was really done. She was a great teacher. When I went to college, I studied acting, thinking I was going to be the next Ben Vereen or Joel Grey, but I was 17, gay and away from home. I had a blue mohawk and was not exactly the all-American boy type they were looking for. A teacher told me that I should audition for those “weirdos” in the modern-dance department, so I did. When I told my parents that I was transferring from drama to modern dance, they weren’t thrilled. Later when my father came to see me with Bill T. Jones — which was very fist-in-the-air political — he’d turn around to the people behind him and say [with a thick Irish brogue], “Did ja happen to get any o’ that? ’Cause it went right over me head.” It was a great conversation starter. I’d say, “Dad, you go to church but to me this is where I make sense out of a chaotic universe and here you are talking to strangers about issues. That’s art doing its job.” I toured the world with Bill T., which he was proud of, but it was “STOMP,” the big commercial hit, that he really loved. And he loved seeing the Seán Curran Company and our nonprofit, Curran Events, Inc. One thing I’m really proud of is that I graduated from NYU and was named the chair of the dance department before he died. But we went through fire. I hated him as a little boy but in the end he was proud.

PGN: So, ever have to perform “STOMP” with a headache or hangover?

SC: Well, another part of my story is that I’m 22 years sober! I spent 10 years with Jones/Zane seeing friends all around me dying of AIDS. It was a time when you wanted to stay numb and I wound up in rehab. I got the job with “STOMP” just after I got sober. [Laughs] They called the Sunday matinee “The Hangover Show,” and at the time sex, drugs and rock and roll were rampant. People would sweat and it smelled like a brewery backstage, but I somehow stayed sober through it all. I was the first gay “STOMP”er and I’d get notes like, “A little more working-class, Mr. Curran.” Which meant, “not so gay.” But they were really proud to have a diversified cast.

PGN: I read that you were a cultural ambassador during a tour of Central Asia. Was there certain protocol you had to follow?

SC: Yes, we went to D.C. for briefings. We were traveling to Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. I was worried about being gay in those countries and they told me that it was an issue especially in Turkmenistan, so I looked it up and, until 2008, if you were gay or perceived to be gay, you were pushed off a cliff or they could build a wall of concrete and tip it over on you. On the other hand, they believe that lesbianism doesn’t exist; it’s just something that the West made up. There’s a new dictator now so it’s a little better, only punishable by two years in prison. There were also some African-Americans in the group and it’s very rare to see a person of color there, so that was a concern. But we did a lot of outreach classes and were received very well. They don’t have modern dance there; they have folk and ballet and whatever the kids see on MTV. I’m assuming that, because we were a dance company, that some of the audience was probably gay, but I could tell it was very difficult there. I remember a high-school kid who was nattily dressed and spoke English well. He came up and I just thought, This poor kid, I can’t imagine what it’s like for him. Of course I couldn’t say anything, but I invited him to the show. He came with his friend who was obviously lesbian and I had a sense of relief that, even in the middle of Central Asia in a repressive culture, you can still find your tribe.

PGN: Any specific rules that stand out?

SC: In Muslim countries, you don’t touch anybody with your left hand, you hail taxis with your palm down, don’t cross your foot and show the sole of your shoe and don’t touch the head; the head houses the soul and a touch puts it in jeopardy — little things that I’d never heard of or imagined. We had to be polite about eating food that was offered and that included horsemeat. Luckily, there were no vegetarians in our group.

PGN: The first R-rated movie you ever saw?

SC: My father took me to the drive-in and they were playing “The Graduate.” I don’t think he knew. Right away I thought, I’m not supposed to be watching this!

PGN: When did you come out?

SC: Well, I went home for the holidays mid-’80s and my father picked me up alone, which was unusual. I was thinking, Where’s my mother, where are my sisters? I thought, Oh God, somebody died. We drove in silence for a while and then he said, “I just read the Times story about the A-I-D-S thing. I don’t want to talk about it but I want to make sure you’re taking care of yourself.” I thought he was opening a door so I told him about the guy I was seeing, that I loved him and we were in a monogamous relationship and he cut me off and said he didn’t want to talk about it. I just wanted to fling myself out the car door, in dramatic fashion. As we pulled up to the house he said, “I don’t want you to ever tell your mother or sisters. It would kill them.” I was torn between thinking how dare he and being glad that I was off the hook with my mother. Fast-forward 10 years and the family was on the way to Ireland for a wedding. I couldn’t make it but the story is that my mother kept going on about when it would be my turn to get married, speculating that it was my career or just not finding the right girl that was holding me back. Finally my sister blurted out, “Mom! Seán’s gay!” It was very dramatic that day on the Air Lingus flight. When they came back, my parents wanted to have a big meeting to discuss it. They refused to talk about it inside their Catholic home so they came to New York. My mother was upset because she’d wanted all her children to meet in heaven and was afraid it wasn’t going to happen. My father wanted to know how we did it: who was the boy and who was the girl. It was surreal. My mother was worried about my soul and my father was worried about my dick. Instead of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” we had “Don’t Ask, Don’t Listen.” He finally said, “So what do you want now? A sign on the lawn?” I told him just the ability to bring a partner home for Christmas would be fine. He told me it would never happen. I was 32 at the time. He just died a few years ago and I never was able to bring someone home, but time did help and it got better. I know it was tough for him too. I was the only boy and the only Curran this side of the Atlantic.

PGN: Has your mom gotten better?

SC: Not really, we just don’t discuss it. She would never ask me if I met someone or how a partner was doing.

PGN: Has your work reflected what you’ve been through?

SC: I made a solo piece that addressed it called “Real Boy.” It used the Pinocchio metaphor of wanting to be accepted as a real boy. I had a marionette stage and it started with my pants down, in a kind of shaming thing. I did a lot of LGBT representation from early on; if I had a man and woman dancing, I’d have two same-sex couples as well. My dancers used to ask each other, “So are you dancing homo, hetero or lesbo tonight?” I often include race and orientation as themes. I did a piece called “Art Song Dance” and in it the two women kissed. When we played in Reno, we got letters because it wasn’t family-friendly enough — in Reno! The land of gambling, prostitution, quickie divorces and billboards with giant pictures of Chippendale dancers in next-to nothing. Anyway … I’d like to think I’m a humanist: I make dances about what it’s like to be here on planet earth, good and bad.

Dance Affiliates presents Seán Curran Company April 6-10 at Prince Theater, 1412 Chestnut St. For tickets, visit princetheater.org. For more information on Seán Curran Company, visit www.seancurrancompany.com.