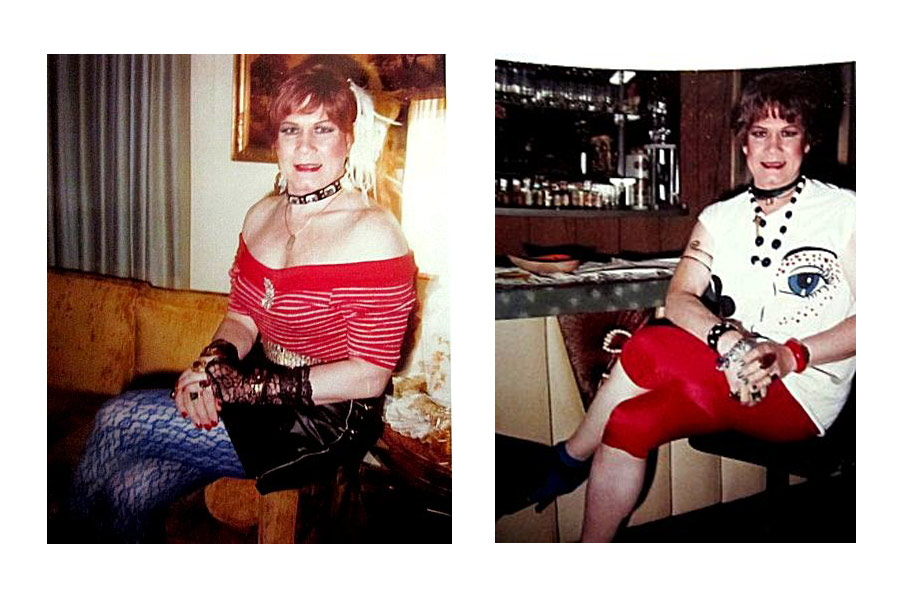

The only person in the world who would have a pair of star-spangled, beaded bloomers was Donna Mae Stemmer, said Michael Byrne of his friend, the longtime City of Brotherly Love Softball League player and cheerleader who died of a heart attack in June. Stemmer was 82.

Byrne inherited those bloomers while a number of Stemmer’s other fashions went to Philly AIDS Thrift.

“She was a patriot,” Byrne said. “She was very proud to have defended her country.”

Stemmer, a Korean War veteran, served in the U.S. Army for over 30 years. She reached the rank of lieutenant colonel and received 25 decorations, including the Distinguished Service Award and Commemorative Medal in 2008.

Stemmer lies buried in Brigadier General William C. Doyle Memorial Cemetery for veterans in Wrightstown, N.J. But the name on her headstone reads “Donald R. Stemmer.” She had not legally changed her name.

“That makes me very sad,” Byrne said. “I just think it’s a sin that her wishes were not able to be met.”

Last wishes

In 2008, Stemmer lobbied Arlington National Cemetery to allow her headstone to reflect her female name and affiliation with the LGBT softball league. Arlington denied her request, she said.

“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” the military policy that prevented gay people from serving openly, also prohibited LGBT references on military headstones, Phyllis B. White, an Arlington spokeswoman, told PGN at the time. “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed in 2010.

The legal service name on the discharge document is what gives someone eligibility to be buried in Arlington, Steve Smith, spokesman for the cemetery, told PGN in December. He added that Arlington follows federal Department of Defense policy regarding veteran burials.

The National Cemetery Administration, which oversees cemeteries through the federal Department of Veterans Affairs, excluding Arlington, also has a policy to use the veteran’s legal name at the time of death on the headstone, said Jessica Schiefer, spokeswoman for the administration. She said LGBT references could be allowed in the space for “terms of endearment” on the marker.

“We honor the veteran and/or the family’s wishes as to what their terms of endearment are,” Schiefer said.

New Jersey burial

Stemmer’s headstone at the New Jersey cemetery was approved by her next-of-kin, said Kryn P. Westhoven, spokesman for the New Jersey Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, which manages the Doyle cemetery.

“When the family requested a grave marker, they put down the name as Donald R. Stemmer,” Westhoven said. “Nothing was indicated for a name change to Donna. The funeral home also had the name as Donald.”

Westhoven said the next-of-kin signature is illegible on cemetery records, but it was witnessed through proper channels at the time.

He said the cemeteries under the purview of New Jersey Military and Veterans Affairs follow the rules from the federal VA.

“As of right now, they have not given us guidance” in reference to transgender burials, he said. “They’re the ones that give the guidance, not only to the state cemeteries, like ours, which receives federal funding for burials, but they also control the federal cemeteries.”

Eric Powell, acting director of the memorial programs service with the federal VA, said his sense is that there is no prohibition of burials for transgender veterans.

“A veteran’s a veteran,” he said. “We will inter them in the cemetery of their choice.”

Powell explained the procedure: When a veteran passes away, the family contacts the national scheduling office in St. Louis, Mo. That office goes through the eligibility checklist by evaluating the veteran’s length of service, manner of discharge and any military honors. The family selects the cemetery, and practical arrangements for the burial can take place.

Saving Stemmer’s fashions

Many of Stemmer’s friends did not know she was buried with a male name.

Tom Brennan, founder of Philly AIDS Thrift, said he was surprised to hear about the headstone. He said Stemmer’s brother helped him coordinate the preservation of her glamorous fashion collection. There were hundreds of earrings, necklaces and bracelets, as Byrne recalled, as well as a mass of crinoline.

Soon after Stemmer died, Brennan said, “One of her friends called and said, ‘Listen, I’m afraid this stuff is going to get thrown out.’”

Brennan was put in touch with Stemmer’s brother by phone. He doesn’t remember the brother’s name, but said he lived out of state.

“When he knew what we wanted to do, he was really helpful,” Brennan said. “He was hugely accommodating. He made keys to the house available. We had the run of the house for three days.”

Stemmer lived in Pennsauken, N.J. Brennan remembered the steaming hot temperatures inside her house in mid-July, just a couple weeks after Stemmer was buried.

Proper burials

Transgender veterans do have a pathway to receive burials that recognize their gender identity, said Matt Thorn, interim executive director of OutServe-SLDN, a Washington-based advocacy organization for LGBT service members.

“You can’t just tell them what you want,” Thorn said. “They have to make sure things line up from an administrative perspective.”

He said the first thing a transgender veteran should request to change is the DD214 form, which is a one-page synopsis of the person’s time in service. The veteran should also submit documentation of a legal name change. Each branch of the military has a review panel. It can take between six and 18 months to effect the record changes.

“It’s not because of it being an LGBT issue,” Thorn said. “It’s more because they’re processing thousands of requests, anything you ever wanted changed on your formal paperwork.”

But now that every branch of the service has dealt with LGBT-specific changes, Thorn said a precedent has been established for how to handle them efficiently.

Thorn said OutServe worked with a transgender veteran who completed her paperwork changes last year, so she can receive a burial in Arlington with her appropriate name.

Thorn said it would be “very difficult” to make changes to a veteran’s burial posthumously.

“You’d have to cite extraordinary circumstances,” he said.

Overall, Thorn feels optimistic about the treatment of transgender service members. He noted a standalone transgender clinic opened last month at a VA clinic in Tucson, Ariz., and said the VA and Defense have “really been trying to make strides in transgender veteran care.”

“We’re on the verge of open transgender service,” Thorn said.