The first time I saw two men dance intimately together was not at Woody’s or Equus but on stage during a Philadanco performance.

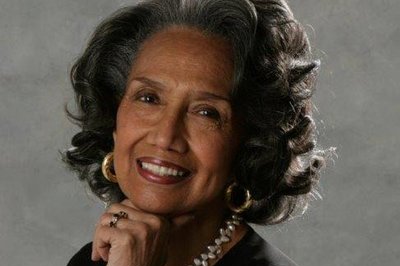

Philadanco is the world-renowned dance company that has been breaking barriers and making stars since 1970. This week, PGN spoke to honored “living legend” Joan Myers Brown, the company founder and a community friend.

PGN: You are one of the most-awarded people in Philadelphia. You’ve been honored as a Master of African American Choreography by the Kennedy Center, won the prestigious Philadelphia Award, have a book written about you, have traveled the world and have worked with some of the great entertainers of our time. I think you’re also the first person I’ve ever interviewed who has their own day! [Nov. 7, 2010, was declared Joan Myers Brown Living Legacy Day.] And yet you’re one of the most down-to-earth people in Philadelphia. Have you always lived here? JMB: Yes. My mother, Nellie Lewis, was a nuclear-research and chemical engineer. She was a pretty smart old lady. And my father, Julius Myers, was a chef and restaurateur. He worked at a lot of the top restaurants in town. I remember that during the Depression we ate very well. He’d bring home food hidden up his sleeve or in his back pocket. I tell people I never knew that butter was square because he’d put a stick in his back pocket, where it would mold it the shape of his pocket on the way home. When he put it in the fridge, it would harden to the shape of his body!

PGN: He put the butt in butter! JMB: [Laughs.] Yeah, back then, while other people were in line for government cheese, we had Brussels sprouts and asparagus, filet-mignon sandwiches, you name it.

PGN: Any siblings? JMB: No, I was an only child. We were never close to any extended family. But I’ve made up for it — I have three daughters, six grandkids and a thousand kids from teaching over the years. Most of them come back and help too.

PGN: What were you like as a kid? JMB: Bad, bad as the devil. My fifth-grade teacher used to take me to her house because my mother was at her wit’s end with me. I think I was just bored. I’d just get up in the middle of class, take off my shoes and walk around. I always wanted to do things my way. I remember one teacher told me to stop pressing the pencil so hard because I was tearing the paper, so I wrote the next paper so light he could barely read it. I was a bad kid. I think that’s why my mother took me to dancing school. But it was 50 cents a week and when I lost my dancing shoes, she refused to buy more.

PGN: Did you dance barefoot? JMB: No, I stopped. I didn’t dance again until I was in high school. My gym teacher got me involved again.

PGN: What was the first dance you saw? JMB: I went to see “Swan Lake” at the Academy of Music. It was beautiful but it didn’t have any impact on me. All the dancers were white so there was nothing for me to relate to. But then I saw Katherine Dunham at the Locust Street Theatre and that made a huge impression.

PGN: Which shows you the importance of visibility, whether you’re black or gay; we need to see ourselves reflected in the world. What discipline did you start with? JMB: Ballet. Subsequently I learned about Janet Collins, who was the first black ballerina to appear at the Metropolitan Opera. You hear that and you start thinking about possibilities. Though I recall that Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo told Collins they would only accept her if she painted her face and skin white. She declined.

PGN: Wow. So what things did you like to do, aside from dance, as a kid? JMB: I actually thought I was going to be an artist. I liked water colors and painting. But once I got started again, I was drawn to dance. I studied at the Sydney School of Dance on Market Street. Other schools like Dash Studios wouldn’t take me because I was black. Then one of my girlfriends got a job with a nightclub revue and was making a lot of money. Flo Sledge — her daughters are Sister Sledge—left and I took her place. I worked there for a lot of years before I started working some of the better shows — cabarets with Pearl Bailey, Cab Calloway and Sammy Davis Jr. I did shows in Vegas, Montreal and Miami. One day I woke up and said, “This isn’t what I really want to be doing. Maybe I can teach some little black kids ballet and they’ll get a chance in the next era.” That next era is still trying to happen.

PGN: Favorite experience? JMB: I’m from Fordham Avenue. I never imagined that I’d travel the world dancing.

PGN: When did you open the Philadelphia School of Dance Arts? JMB: In 1960, while I was still dancing. I was performing and choreographing shows, mostly at Club Harlem in Atlantic City. I taught ballet in the afternoon and shuffled off to Buffalo every night.

PGN: What was the worst aspect of entertaining? JMB: Some places you had to mix. After the show you had to sit at the bar and socialize with the patrons. I wasn’t a drinker so I didn’t care for it. I’d stay in the dressing room or hide in the bathroom. [Laughs.] That’s one time segregation actually helped me! Because in places like Vegas, when I was with Pearl, I was the only black girl in the show and I wasn’t allowed in the clubs. So the white girls had to mix and I got to go home!

PGN: That’s funny. What was the hardest part of starting the school? JMB: The hardest part was the commute those first years. I went to sleep at the wheel one night and after that, my boyfriend at the time was nice enough to drive me back and forth or I’d ride the bus. I’ve been very lucky in that I’ve always had people help me with the school — my mother and friends. To this day, there are people who see that you’re doing something good and want to help.

PGN: When did you start Philadanco? JMB: I started the dance company 10 years later, in 1970. I had all these trained kids and nowhere for them to dance. Pennsylvania Ballet and the other dance companies weren’t using black dancers so we created our own company. I figured it would give them a start and then they would move on to New York or overseas. The first person to leave was Gary DeLoatch, who went to Dance Theater of Harlem.

PGN: You are known for training dancers only to have them snatched by other companies. JMB: [Smiles.] Yes, last year two of my dancers went to Alvin Ailey. But I’m glad there’s someplace that they can go, something to reach for. A lot of them are going to Broadway now for the money. They’re not as invested in the art as they used to be.

PGN: When did you first become aware of the gay community? JMB: Oh, I’ve been aware of it since I started dancing in high school. We’d go to parties with guys from Sydney’s and then at a certain point they’d put us girls out! I never felt a difference in people because of their sexual orientation. People are people, though I notice that the guys — especially if they’re away from the family for the first time and are just coming out of the closet — go a little crazy when they get here. [Laughs.] Sometimes I have to get them to pull it in a little. My best friend forever was gay. Growing up, I was always his fake date and he was my safe date. He just died last year. But with the guys, I’d say, “You can do whatever you want off stage but when you’re portraying my characters, I want you to butch it up! If I wanted all girls, I’d hire all girls!” But I’ve noticed more and more of the girls are coming out, and younger each year.

PGN: Which brings me back to the show I saw with the two male dancers. That was very progressive for back then. JMB: Yeah, it depended on the choreographer. Talley Beatty did a lot of cross-gender dancing. It was never an intentional statement on my part, I just didn’t care if we did it. I choose the piece on its own merit.

PGN: Did you ever get any flack about it? JMB: No, the only time was when Zane Booker did his first duet with a guy because he’d just come out to his mom and he wanted everyone to know he was gay. I heard more comments about that one than anything else. But that was his statement and we honored it. [Laughs.] Though I always say to the guys, “Everyone knows you’re gay, especially your mom! Who are you trying to fool?”

PGN: That’s one heck of a way to come out! I imagine the AIDS epidemic had a big impact on you.

JMB: I felt like someone had come in here with a big broom and just swept all my people away. I lost lots of guys. It was terrible, a whole slew of guys — 28, 29 years old — and they just were gone. People would gossip, “You know, he got ‘the AIDS,’” and I’d say, “What’s ‘the AIDS?’” It was awful.

PGN: Well, back to you. You’ve been all over the world. JMB: We’ve been to 20 countries and just about every state. I never imagined it. I was just trying to find a way to give my kids something to do. To help them move on, but instead they stayed and we grew!

PGN: I read an article about your experiences abroad, especially going to Poland where the airline lost all your costumes and you had to make the guys dance in nothing but their jeans. JMB: Yes, when they started to give me a hard time I told them, “When you go to the clubs you have no problem taking off your shirts, you can do it now!”

PGN: Then you had to fight to get paid and also had people throw garbage at you. JMB: It took me two years to get paid but I did it! And yes, people threw garbage at us and called us monkeys as we walked around the city. Racism doesn’t change. I started the company in 1970, it’s 2013 and look at Pennsylvania Ballet — they still only have one black dancer. And when they do, it’s usually a male dancer. American Ballet Theatre has Misty Copeland but she’s so fair-skinned. I remember talking to Raven Wilkinson, also with the Ballet Russe, and how she had to promise not to let anyone know she was black. It worked for two years until they were down South and a hotel elevator operator recognized her and reported her to the management. They kicked her out of the hotel. Then when they were in Alabama the KKK heard there was a colored girl in the show. They came into the theater and onto the stage demanding to know which one was the negro. No one said anything but after that, the company suggested it be her last season. It doesn’t change. All these companies are getting money to do outreach into the black communities but they never hire anyone. Look at Michaela DePrince, who was featured in that documentary “First Position.” They made a huge fuss over her but nobody from the mainstream companies hired her. Things don’t change much, they just shift; people used to be more direct with racism and now it’s more subtle.

PGN: You’ve also dealt with homophobia. JMB: It’s so sad that homophobia gives dancing, especially ballet, such a stigma. I have one little boy in the school and his dad will let him do hip-hop or acrobatics but refuses to let him do anything he thinks is unmanly. I had another boy in Vegas who was with me from the time he was 10. When he was 15, his mother remarried and the new husband decided he wasn’t going to raise a gay stepson. He said, “I’m going to beat that shit out of him,” so I got him out of there and moved him into his own apartment. He was able to keep dancing and went on to join Alvin Ailey and was with Cirque du Soleil for years. He now has his own company and of course the stepdad is now all [uses a gruff voice], “Yeah, that’s my boy!”

PGN: Now for some random questions. Who was your celebrity crush? JMB: Oh, Billy Eckstine. And I got to work with him. I thought I was in seventh heaven! My daughter always tells me Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie are my extended family because I’m always reading about them and their kids. I just love her! Of course, she’s a real bitch! She does what she wanna do the way she wanna do it!

PGN: In another life, I probably was a … JMB: Dancer from India. A fortune teller told me that once and that’s how I found out that my grandfather was from Sri Lanka! And I know what I’m going to do in my next life: I’m going to open up a bar for big, beautiful broads! No skinny ballerinas. Men like to act like they like skinny broads but they actually prefer big girls. And I’m going to get drunk with the customers while the big, beautiful women dance and I’ll make a lot of money!

PGN: Who was your first love? JMB: He was an amateur boxer. We had a phone with a party line and he used to call me. I was on cloud nine. Before that, the phone used to be on the corner and everyone on the block used the same phone.

PGN: Any scars? JMB: I have one on my ankle from when I was a kid. I fell off the curb and got hit by a truck and oh Lord, I have a huge scar from my C-section. [Laughs.] I told my daughter, “You done ruined my body!”

PGN: I still can’t believe I once … JMB: Received the National Medal of Arts from President Obama in 2012. We were preparing for an overseas show and I got a call from the White House asking where I was going to be on the 10th. I told them I’d be in Chile and they said, “No you won’t, you’re being honored by the president.” So I sent the kids to Chile and went to Washington. It was surreal but I didn’t really get to enjoy it; the ceremony was at 3 and by 4 p.m. I was on a plane to South America to join the company. It was an honor but if it was Bush, I would have told him to mail it to me!

PGN: You have some shows coming up in December at the Kimmel Center. What can we expect? JMB: I like to see young choreographers get an opportunity for their work to be seen, so I’m highlighting the work of Christopher Huggins. I don’t want us to get stale so each year we change it up.

PGN: I understand that you support artists in other ways. JMB: Yes, we teach props, staging, everything. I have a girl in Vegas now doing costumes for Cirque and I have a girl from Brazil who just wrote me the nicest letter about what she learned here outside of dance. She really got what we’re all about. It’s not just about teaching dance, it’s about making better people.

For more information on Philadanco, visit www.philadanco.org.

To suggest a community member for Family Portrait, email portraits05@aol.com.