As a child, transgender author Alex Myers listened with rapt attention when his grandmother regaled the family with tales of their New England ancestors.

The devoted amateur genealogist loved telling her grandchildren about distant relatives who had crossed the Atlantic on the Mayflower or accompanied Benedict Arnold on his ill-fated expedition to Quebec.

But it was the story of Deborah Sampson that really caught the budding writer’s attention. Towards the end of the Revolutionary War, Sampson disguised herself as a man, adopted the name “Robert Shurtliff” and enlisted in the Continental Army.

For 17 months, Sampson drilled, bunked and fought side by side with her fellow infantrymen, enduring the privations and the dangers of military life. Despite being seriously wounded in a skirmish, she returned to her regiment, the ruse still undetected. After hostilities ended, a terrible fever sent her to the hospital, where a doctor discovered that this particular soldier was actually a young woman.

Even as a child, Myers recognized that this bit of family history was special.

“I just remember as a kid hearing it and thinking, ‘Crazy!’ It just sounded so wild to me, but also so natural that a woman would see the Revolutionary War and say, ‘I want to be part of that.’ I mean, who wouldn’t?” he said.

Sampson’s story has special meaning for Myers, who came out in 1995 during his senior year at Phillips Exeter Academy and went on to become Harvard University’s first openly transgender student. During that period, he found inspiration in the example of the brave colonial woman who bucked societal pressure in order to lead a life of her choosing.

“When I eventually came out,” he said, “I thought back to hearing that story and sort of realized what resonance it had to me at the time, that sort of casual affirmation that, yes, other people desired the very thing that I desired, even hundreds of years ago.”

Like Sampson, Myers has chosen to lead life on his terms. As an undergraduate, he successfully lobbied Harvard’s student council to amend its nondiscrimination clause to include gender identity as a separate category. After graduating, he coached and taught at St. George’s, a boarding school in Rhode Island, where he eventually rose to become chair of the English Department. He has also been a husband for 11 years, first committing to his partner in a civil union, then marrying her when that union was annulled by the legal transition of his status from female to male.

Now a Lannan Associate at the Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown, the former high-school teacher is modest about his accomplishments.

“I would say what I did at Exeter and Harvard — and I’d like to think at every place that I’ve lived and worked after that — is to live as a well-adjusted, normal, hardworking, successful, intelligent person who is transgender and who is not embarrassed, ashamed or afraid in any way of being out as transgender,” he said.

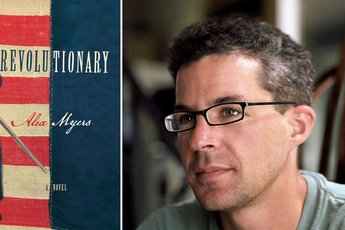

Although usually understated, Myers is excited about his debut novel, “Revolutionary,” which chronicles Deborah Sampson’s life as a soldier. The novel will be available in January; it is the first book on Simon & Schuster’s fiction list to be written by a transgender author.

Myers began to contemplate writing a novel in 2010, while he was working on an MFA in creative writing at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. He mulled over various possibilities, but Sampson’s story quickly emerged as his ideal subject.

“I was writing a lot in the MFA program,” he said, “just writing short stories and essays and feeling like, Boy, do I ever want to try writing a novel? And as soon as I thought about that, I thought, Oh my gosh! I have to write about Deborah Sampson.”

The result is a thoughtful fictional account of Sampson’s 17 months as Robert Shurtliff, colonial soldier. Although the tale has elements of adventure, Myers focuses on Robert’s experience as an ordinary infantryman, including the drudgery and fear that the real-life Sampson undoubtedly experienced. As the novel progresses, Robert goes from being a raw recruit to a combat-tested veteran, but his struggles aren’t limited to the battlefield.

By embracing Robert, Sampson is able to evade the limited possibilities society offered women of her class and gender, whereas Robert is judged according to his ability. How well he learns close-order drill and how he reacts under fire are what count to the men in his unit. The more Robert is accepted by his peers, however, the more difficult Sampson’s conundrum becomes. Her attempt to understand who she is and how she will lead her life are the issues Myers etches in sharp relief.

“I think the novel explores the question of identity and what it means to be true to who one feels oneself to be,” Myers said. “I think it also looks at the question of desire on many levels, like personal desire, as well as a desire that goes beyond oneself.”

The author addresses these themes with a light touch, allowing them to emerge from Robert’s day-to-day travails. In fact, it is those struggles that highlight just how remarkable the actual Deborah Sampson was.

In reality, Sampson’s long life was marked by poverty, frustration and illness, leavened only by the 17 months of freedom and opportunity she experienced while in the army. The late historian Alfred F. Young examined her life with great sympathy in his 2005 book, “Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier.”

As Myers was working on the novel, he not only studied that book, but he benefitted from conversations with its author.

According to Myers, Young “read through the novel and offered notes on it and kind of guided me through a couple of things that I had maybe misinterpreted. He was just very patient and it was so evident through speaking with him that he had a deep passion for this. And it wasn’t his life’s work — he wrote more extensively on other areas — but it was clearly something that he loved.”

The facts regarding Sampson are few but straightforward. She was born in 1760 in Plymouth, Mass. Her parents were descended from Mayflower passengers, but the family struggled to get by. A middle child, she appeared to be unloved and was pushed into indentured servitude as a girl. Enlisting in the army was clearly an escape from a lifetime of sheer drudgery.

After the war, Sampson drifted back to Massachusetts to live with relatives in Sharon. Eventually she married Benjamin Gannett and had three children. As a farmer, Gannett was no more successful than her parents and the couple frequently lacked money.

Like many veterans, Sampson petitioned the government for a pension, but her difficulties were compounded by the fact that she used deception to enlist. Consequently, she appealed for help to her commanding officers and to notable public figures, including Paul Revere. In an 1804 letter to a congressman regarding her situation, the famous silversmith and patriot wrote, “I think her case much more deserving than hundreds to whom Congress have been generous.”

One respite from these dreary circumstances was an 1802 lecture tour Sampson undertook to raise money, which made her America’s first itinerant female lecturer. After delivering a highly embellished speech about her wartime experience, she would return to the stage dressed in her military uniform and perform the manual of arms. Public reaction was warm, but she missed her children. In later years, Sampson was frequently ill. She finally passed away in 1827.

These facts may appear uninspiring, but one hopes that Myers’ novel will show the reading public just how revolutionary Deborah Sampson’s quest for personal liberty and self-determination were.

For more information on Alex Myers and his forthcoming novel, visit alexmyerswriting.blogspot.com/.